Famicom cover

Capcom had been successful throughout the 80s for their many kinds of action games, which makes it something of a surprise that they produced an adventure game as their third and final entry for the Famicom Disk System. Although it’s mostly been forgotten, Samurai Sword is a simplified, story-driven adventure that’s worth a shot if you’re looking into trying early Japanese adventure games.

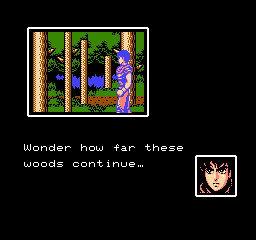

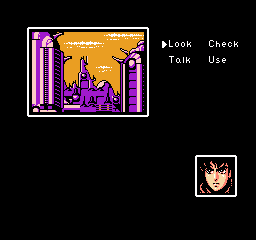

The dark priest Soron is using his terrible powers to enshroud the world in darkness, and countless warriors and wizards fight in vain to stop him. You play as a nameless swordsman just about to fall to Soron, when you’re whisked away to a forest and told that you’ll need to find a Light Mage in order to make things right. You set off on your journey, encountering ancient ruins and technologies along the way.

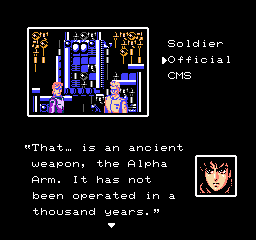

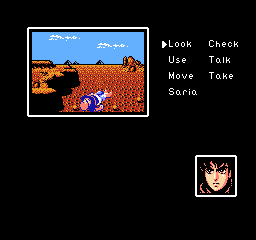

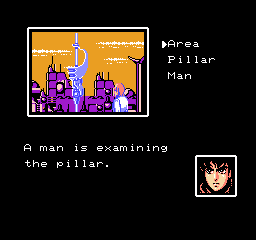

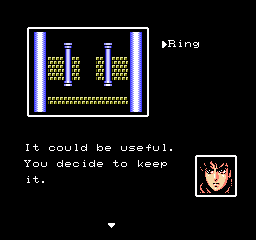

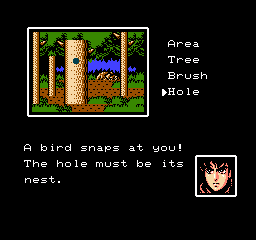

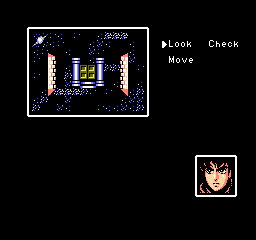

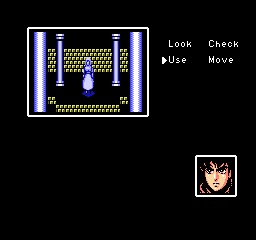

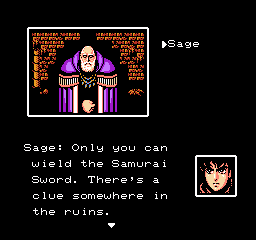

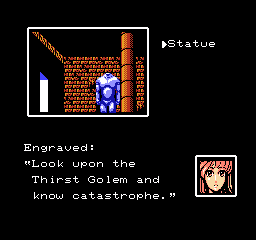

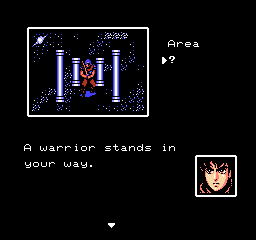

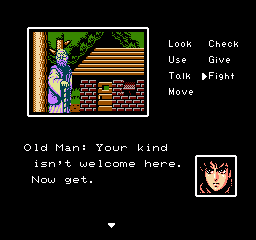

Samurai Sword is an adventure game where you have to complete whatever tasks you’ll need to do in any given area, such as finding a missing person, exploring an area, or acquiring a special item, before you can move on. There’s a command menu that will present a handful of actions to perform, like talking to people, examining notable parts of each locale, taking and using items. What’s neat is that these commands only appear if they’re needed in any given room, which cuts down on going through all the actions if you’re stuck.

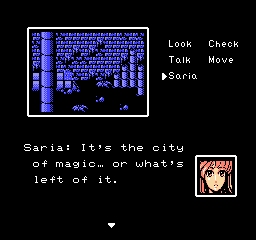

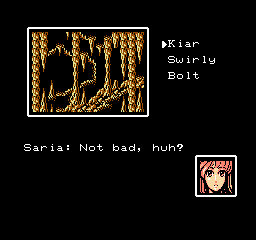

Early on, you’ll meet up with Saria, a girl who can cast magic spells and generally help you out if the situation calls for it. Sometimes, this involves talking to her to get her to do something, and other times you’ll have to take control of her by picking the “Saria” option on the menu. It can be a bit inconsistent trying to figure out what thing you’ll need to do, but this works out intuitively for the most part.

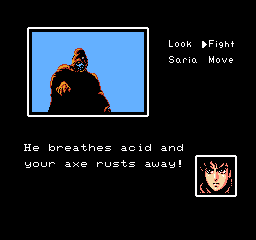

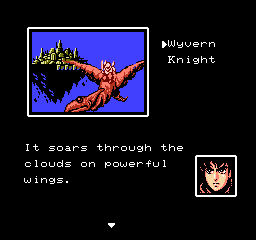

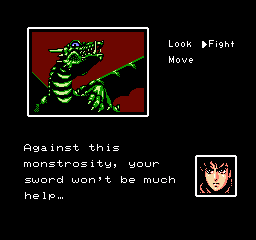

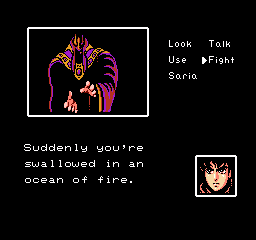

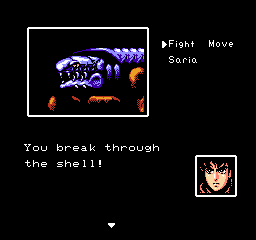

Saria is mainly helpful in the handful of action sequences that occur throughout the game, where you face off against an enemy. You’ll need to figure out a strategy to overcome them, which can involve using the right spell, a certain item, or a combination of actions. They add a nice bit of tension to the adventure, as there’s the very real risk of you dying and being forced to start over from the beginning of the section.

This can be quite tedious, since sections can take a while to complete and sometimes have you doing a very specific sequence of examinations or actions to obtain an item or make progress. These are logical enough once you’ve figured out that sequence, but it’s still perhaps a bit too long-winded especially when some of these fights act as the ending of the chapter. At the very least, you can retreat from most of them and consider what you could do before heading back in, so they’re not completely punishing.

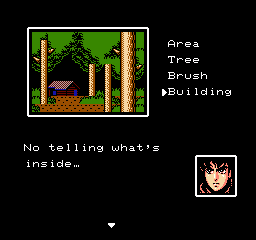

Structurally, each section of the game is self-contained, meaning you don’t need to worry about hanging onto items apart from your sword and a special orb that’ll help you see through illusions. It also allows for a greater mechanical variation, where one section will have you exploring a desert for the entrance to ancient ruins while another has you asking around a town to learn of its secrets. Each area is also quite small, usually comprised of a dozen or so rooms which makes it easy to mentally map everything out and revisit places if you’ve overlooked something.

Combined with the contextual commands and the straightforward nature of most puzzles, this makes for an adventure game that’s more streamlined than its contemporaries. You’ll still have to examine objects or talk to people a couple times to make sure you haven’t missed anything, but this is a more approachable game for newcomers. The only major issue is in relation to the save system. You can only save at the end of a section, which is inconvenient when other adventure games allowed you to do so at any time. Also, you have just one save slot, despite many FDS games granting you multiple slots if you needed it.

If you can roll with those inconveniences, there’s plenty to enjoy in an adventure that’s got a surprising amount of story emphasis. There’s a fair bit of dialogue, as you and Saria discuss what to do during most situations, and the eloquent prose for the action sequences creates strong impressions of the actions you or the enemies take. Although the focus is mainly on the adventure at the expense of some rather standard characterization, it results in a journey that’s as memorable for the narrative set-pieces and character beats as it is for the puzzles and gameplay.

This is furthered by some solid presentation. Samurai Sword was the first game to be composed by the legendary Yoko Shimomura of Kingdom Hearts fame, and while the music can sometimes get repetitive, they provide atmospheric melodies that give each section its own mood. The world is experienced through small but detailed windows that utilize unique colors for the various places you travel to, as well as ensuring notable parts of each room are easy to see and remember when you’re on the lookout for items or clues.

It’s hard to know what kind of impact Samurai Sword had due to the overall anonymity of its existence and most of the people who worked on it, but it’s worth mentioning that Capcom would later develop another adventure game just one year later based on the 1987 film Marusa no Onna (though it shares no staff as far as it can be discerned).

Although never officially released beyond Japan, an English fan translation was done back in 2003 by Mute, who translated a handful of other obscure Famicom titles such as Suishou no Dragon and Silviana.

LINKS:

The English fan translation patch: https://www.romhacking.net/translations/699/