- Retro Game Challenge

- Game Center CX: Arino no Chousenjou 2

How long does it take, roughly, for media to go from “outdated” to “nostalgic”? If the video game market is to be believed, we’d probably have to say about somewhere between fifteen and twenty years. The NES was released in 1985, hit its stride around 1988, and twenty years later, we have Nintendo and everyone else finally redistributing their old games legally through digital distribution. The timeline makes sense, of course. It’s about that long that kids have grown up, have some sense of disposable income, and want to recapture the spirit of youth, either for their own fulfillment, or for the joys of a new generation.

Still, there’s more to the phenomenon that just republishing old games. The passage of time has made the greater populace aware that, you know, just because a game is newer doesn’t mean it’s necessarily better. As such, we’re seeing developers go back and mine old properties for old ideas. To whit: many joked (or perhaps were serious) that the killer app for the Xbox 360 back in 2005 wasn’t Perfect Dark Zero or Kameo, like Microsoft would’ve had you believe, but was actually the $5 downloadable title Geometry Wars, whose roots lie heavily in the 1982 arcade shooter Robotron 2084.

The concept of Retro Game Challenge (Game Center CX), published by Namco Bandai in Japan and XSeed in North America, and developed by indieszero, follows in a slightly similar school of thought. Both titles, released for the DS, are collections of retro-style games – none of them actually existed back in the 80s or 90s, but they’re all designed to make it seem like they did. The graphics, the sounds, and the controls are all styled like they were back in the day. The atmosphere is explicitly meant to remind games of the lazy summers they spent in front the TV, playing games all day with their friends, flipping through gaming magazines and trading secrets.

There’s more to the games than mere nostalgia though – each of the games in Retro Game Challenge benefits from over twenty years of hindsight, as well as technological improvements. As a result, they tend to avoid the pitfalls of so many old games, except for the ones they explicitly mean to replicate. It’s true that some are simply clones of existing titles, the kind that probably would’ve been scoffed as ripoffs had they been released years ago, but the genres they tackle are so sparsely populated nowadays that it’s more a cause for celebration than criticism. Even more interesting are the games that combine two or more mechanics from disparate classics – it’s fun to not only recognize the sources, but see how they work in tandem. One of the best examples is Ninja Haggleman 3 in the first title, essentially a mixture of Ninja Gaiden and Metroid. Had that been released fifteen years ago, it would’ve been Game of the Year material.

Still, for all of its occasional brilliance, it’s still a bit conceptually flawed. As much as we all love to think about the NES classics, the truth is that 95% of the things that came out were either forgettable or terrible. None of the games in the collection are bad, per se, but none of them would really stand up to, say, Super Mario Bros. or Contra. Part of this is because they’re too busy emulating older games to come up with anything truly original, but at least the results are usually refined, if not inspiring. Another factor is that the games simply aren’t very long. Most offer only a few levels at most, and can be beaten relatively quickly.

The Japanese release is a tie-in to a retro themed video game show called Game Center CX, a funny little show where a comedian named Shinya Arino is employed at a fictional corportation, also named Game Center CX, and force him to play through Famicom games. There’s usually a specific goal in mind – beat the game, get a certain score, etc. – and the hilariously dramatic music accompanies Arino’s efforts to conquer them. Some of them are classics, but many of them aren’t, and most of the fun comes from the amount of torture Arino and his crew put up with in order to conquer the trials and tribulations of retro gaming. These challenges are usually interspersed with other segments, where Arino and his crew interview Japanese developers or visit arcades. It’s a great show, and while there were efforts to release them on DVD in English, that seems to have fallen through the cracks.

In the game, Arino is portrayed as a maniacal, laughing polygonal face, reminiscent of Dr. Kawashima in Nintendo’s Brain Training game. He’s captured you, the player, and sent you back in time in order to play video games with his younger self. Each game has a series of four challenges – score a certain number of points, reach a certain level – that must be conquered before you can go on to the next. Once you’ve conquered the challenges, you unlock the “free play” for that game, so you can play from start to finish without being interrupted by the various goals.

This structure is both its greatest strength and weakness. If all titles had been presented at start, then most gamers would probably just test out all the different selections, feel a tingly bit of nostalgia for a bit, then either shelve the game or (worse) sell it back to the store. While this gives a reason to learn how the play to game and make them seem less disposable, it expects that the player is fan of all the genres presented. Some people just don’t like racing or puzzle games, and forcing them to play something they don’t want to, just so they can unlock something later on they DO, isn’t exactly the best game design philosophy.

Still, the developers must’ve realized this conundrum, and thus built in cheat codes. At your disposal are several video game magazines, each containing tips and tricks straight from the developers, which can let you conquer most the challenges pretty easily. The second game even gives you the option to skip them completely, if you’ve tried enough times, and bother Arino enough to give you a free pass.

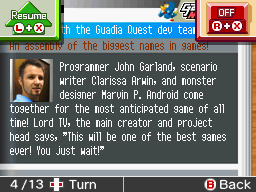

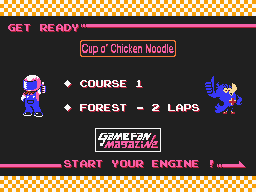

The magazines are more than just a tool, because they also add to the sense of nostalgia. In addition to the strategy guides, they’re full of random fun minutiae, like previews, editorials and sales rankings for other (non-existent) games in the Retro Game Challenge universe. In the Japanese version, the names and portraits are taken from various people in the Game Center CX show. In the North American version, they’re based on real life gaming journalists from magazines like Die Hard Game Fan and Electronic Gaming Monthly. They work under pseudonyms, but it’s usually pretty clear who they are actually are. (“Sock” for example, is clearly Dan Hsu from EGM.)

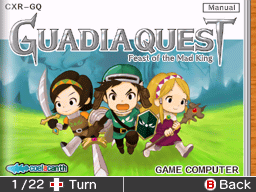

There’s a pretty fun alternate universe of 8-bit gaming that Bandai/Namco invented for themselves, complete with fictional companies to go along with the fictional franchises. The game magazines help this, especially when they comment on the multiple delays of the fabled “Guadia Quest” series, mimicing the similar experiences with Dragon Quest in Japan. Still, as much as XSeed tried to make as much of this apparent to the English speaking audience, some of it is just a bit too faithful. While they redubbed Arino’s comments into English (using famed voice actor Yuri Lowenthal), they left in the Japanese-style living room and Famicom-style cartridges and systems. At the risk of deviating too much to its source material, these aspects probably should’ve been redrawn to more closer match the American NES experience.

The Games

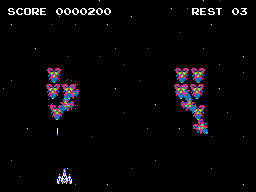

Cosmic Gate is basically just Galaga – you control a ship at the bottom of the screen, firing at legions of aliens that swarm from off the screen before establishing themselves in a set formation near the top. The major differences are the asteroid stages that pop up every few rounds, and a secret warp (the “cosmic gate” of the title) that appears when certain enemies are killed and can skip you ahead a few stages. This is the first game and it tries to set the tone for the others, but frankly it’s a bit dull.

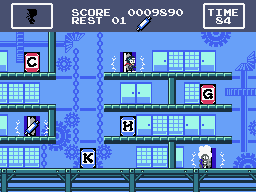

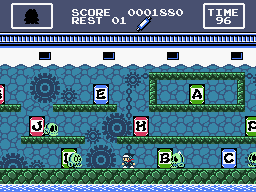

Ostensibly based on Jaleco’s not-quite-classic Ninja Jajamaru-kun, Robot Ninja Haggleman puts you in the role of a tiny little ninja who must clear each stage of enemies. The stages are comprised of several floors, which you can easily jump between, and the screen scrolls horizontally, looping endlessly. Although Haggleman’s main weapons are gear-shapred shurikens, these only stun most enemies – in classic video game fashion, he needs to jump on their heads to kill them. As the game progresses, you’ll come across enemies that are invincible to regular attacks, and must be attacked by leaping on their heads. Clear the stage and the stage boss will pop out. These bosses are introduced as shadows at the beginning of each stage, a nicely classic touch.

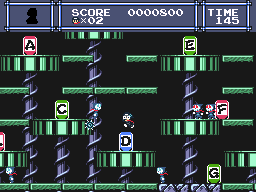

Haggleman can only take two hits – after the first, his eyes bulge out, indicating his health status. Each level is also filled with doors bearing different symbols (the alphabet in the English version, katakana in the Japanese version) and different colors. When you flip one of the doors, all of the doors of the same color are also flipped, injuring any enemy in front of it. If you flip the doors in a specific order (alphabetical order in the English version, the “i-ro-ha” order in Japanese) it’ll change all of the doors to the same color, allowing you to easily turn the tables on your foes. You can also do this in reverse to repair yourself once per life. There are a variety of shuriken power-ups, as well as scrolls which can call upon the aid of Haggleman’s three friends – his sister Koume, his little baby friend Zenmei, or the robotic dog K9.

It’s the first “good” game of the set, but it feels like it’s intentionally gimped to make way for its sequel, which is opened up later on. It’s also quite short, with only eight floors total. The English name might sound a bit odd – in Japanese, it was originally “haguru-man”, where “haguru” means “gear”. “Haggle” is just a weird transliteration of it that loses its original meaning.

Rally King is one of those overhead racing games. There were a number of these released in Japan, like Irem’s Zippy Race (AKA MotoRace USA), Nintendo’s Famicom Grand Prix F1 Race and Konami’s Road Fighter, although these are quite obscure by American standards, who mostly grew up on Super Sprint and RC Pro Am. It’s quite tough to control and more than a bit tedious, although mastering the drifting technique is kinda fun. There are only four stages.

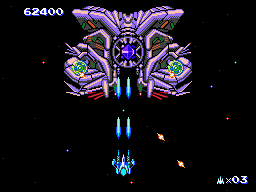

This shooter is developed by Tomato, the same fictional company behind Cosmic Gate, and is sort of a spiritual successor. It’s the Game Center CX take on Star Force and/or Star Soldier, where you fly over floating fortresses, destroy bits and pieces of them for bonuses, and powerup your ship to fire multiple bullet spreads. It’s much, MUCH more advanced than the NES/FC version of Star Soldier though, so it’s as if Hudson made one later in the 8-bit system’s life instead of jumping to the Turbografx-16. It looks fantastic, although it’s only four stages long.

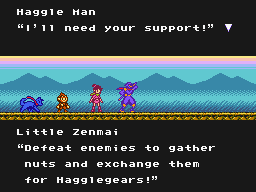

On the surface this sequel isn’t drastically different, but it’s a more involved game, mostly because the stages can now scroll vertically too, so everything feels less claustrophobic. It’s also more difficult, with a larger army of enemies. Now you can choose when to call upon your friends, instead of it automatically being activated when collecting three of the scrolls. There are 17 floors total this time, although it loops after the first eight stages are complete. In the final stage, you fight a boss battle where the final baddie jumps inside a robot, not unlike Dr. Wily in the Mega Man games.

Rally King SP is a parody of those limited edition tie-in Famicom games like All Night Nippon Super Mario Bros (which replaced the sprites with cast members of a late night TV show) and Gradius Archimedes (which replaced the power-ups with ramen bowls.) This particular game is endorsed by a fictional ramen company, whose logo and mascot pop up around the game. Other than the new goals, different cheat codes and some palette swaps, this one is basically the same as the original Rally King, which is really annoying. Rally King wasn’t that great to begin with, and making you play the whole thing AGAIN just reeks of laziness on developer’s part.

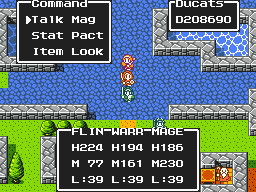

Undoubtedly the most fully fleshed out title of the bunch, Guadia Quest is basically Dragon Quest II – it’s an 8-bit RPG where you control three characters, with random battles and turn based encounters. Although it’s challenging, it’s also quite a bit more accomodating than a typical NES RPG, allowing you to save anywhere. You can also form “pacts” with monsters so you can summon them in battle, similar to Megami Tensei and Dragon Quest V. Although to beat the goal you only need to beat the first dungeon, it’s quite large, and it’ll take roughly an hour or two to grind yourself strong enough to beat it. There’s another rather large dungeon to be had afterwards, if you want to clear the whole game. Obviously fans of classic RPGs will be in heaven – those that aren’t will find it remarkably boring.

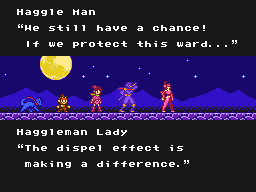

The final title – and best game of either Game Center CX games – completely reinvents Haggleman and turns the cutesy ninja into an anime-styled hero, much how Jaleco completely reinvented their Ninja Jajamaru-kun mascot multiple times. Instead of a simple arcade platformer, this game combines the action of Ninja Gaiden (complete with a variety of sub-weapons activated by hitting Up+Attack) with the non-linear exploration of Metroid, and the result is absolutely beautiful.

Robot Ninja Haggleman 3

Although the game is sectioned into stages, each has branching paths and special items which must be found in order to proceed. Enemies and orbs drop money, which can be used in shops that look suspiciously like the ones in Kid Icarus. When close to an enemy, you’ll slash them with your sword like Shinobi. The intro screen, with its scrolling text and entirely capitalized proper nouns feel a lot like the intro to The Legend of Zelda. The silly cutscenes are also full of stock anime/manga cliches, although they’re all told with sprites instead of movie scenes like Ninja Gaiden. It looks great, plays great, and would undoubtedly have been considered a classic if it had been released for real back in the 8-bit era. The only problem is that it’s dreadfully short, with only three stages, although most of them are quite expansive. It’s also one of the only titles on this collection with a really standout soundtrack – the first level theme is a more intense variation on the title song from the first Haggleman game, which is quite catchy.