- Nosferatu the Vampyre

- Nosferatu (SNES)

The Movie

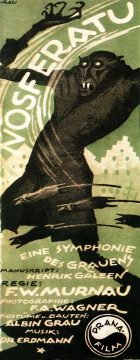

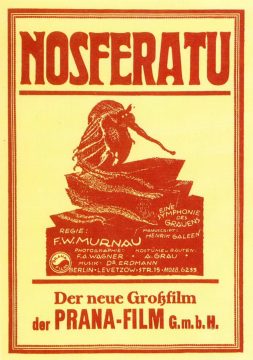

Produced in 1921 and first shown the following year, Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau’s Nosferatu is one of the early formative works of horror film. It helped codify much of the aesthetics and methods of the genre, and directly or indirectly affected just about every single vampire movie made afterwards. Max Schreck’s (even his name means “scare”) delivery of the Count Orlok, with his unnerving, ancient stare, his distorted face and claws is universally recognized as one of the most iconic vampire performances ever. The film Shadow of the Vampire went so far as to muse about the proposition of Schreck being an actual vampire himself. “Nosferatu” has since become a synonym for vampire myths’ more monstrous and arcane aspects, as evidenced in the equally named bloodline in Vampire: The Masquerade. It’s subtitle Eine Symphonie des Grauens (“Symphony of Horror”) is even referenced in many later Castlevania titles. And yet the film was almost made to disappear, long before video games even existed.

Nosferatu was the first film adaption of Bram Stoker’s novel Dracula, but Murnau didn’t actually have license to the original. So the plot was transplanted into the fictional German town Wisborg, and all the character’s names changed. Dracula became Orlok, Jonathan Harker was known as Thomas Hutter, his wife Mina as Ellen, and Van Helsing appears as Professor Bulwer (the Lucy Westenra subplot and several other characters are omitted). This weak attempt at concealing its origins was not enough, and Bram Stoker’s widow successfully sued the production company for copyright infringement, resulting in the burning of the orginal negative and all existing copies. One copy got out, though, and for decades, Nosferatu only lived on thanks to the widespread use of bootlegs. (See, video games aren’t the first medium whose history is saved by piracy!)

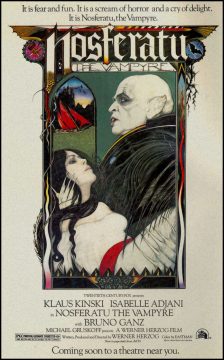

Only in the early 2000s was the film restored to its original musical score and color-tinted glory, but in 1979, Werner Herzog directed a remake of the film with the infamous Klaus Kinski as the Count, titled Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht. (The subtitle translates to “Phantom of the Night”, but the English release was officially named Nosferatu the Vampire.) It is an odd hybrid, reinstating all the names from the Dracula novel (although Jonathan’s wife for whatever reason is Lucy here), as apparently did some copies of the 1922 film too, but keeping their home town in Germany, this time in form of the real city Wismar, which served as an inspiration for the silent film’s Wisborg.

There are three video games that bear the title Nosferatu, although only one is a direct film adaption, whereas the second rather seems to have picked the name just to not be called Dracula, and the last only borrows the silent film’s general image and atmosphere. They were made in three different decades and in three different countries, and deliver an interesting example of the variety of game design sensibilities between eras and regions, just like the Nosferatu films serve as a counterpart to the typical American and British adaptions of the Dracula story.

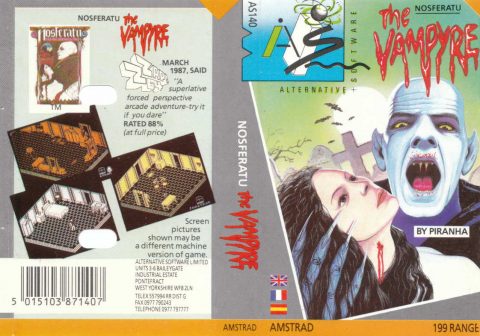

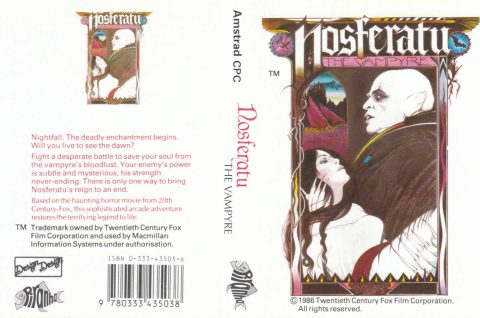

Nosferatu the Vampyre – ZX Spectrum, Amstrad CPC, Commodore 64 (1986)

The 1986 UK home computer game ties in directly not with the original Nosferatu, but with Herzog’s 1979 remake – back then, the video game industry wasn’t quite as fast-lived as today, so licensing a seven-year-old movie for a game was no big deal. Due to its point of reference, the game uses all the original Dracula character names but the changed and abridged German plot.

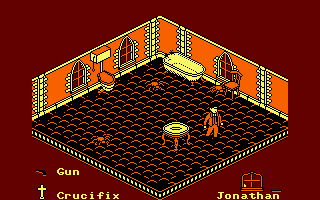

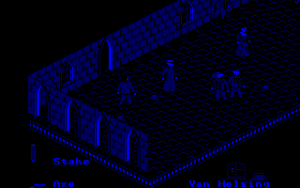

After the 1985 release of Knight Lore, isometric adventure games were all the rage in the UK, and that’s the fad Nosferatu the Vampyre leaped onto. The gameplay is simple: You just walk around and pick up whatever objects. One weapon can be carried at any time, alongside one other item. Unfortunately, everything from picking up stuff to attacking to dropping items is done with one single button. Today it would be called context-sensitive and praised as a feature, but here it doesn’t work all that well. So attempting to attack an enemy more often than not just drops the currently carried item, leaving you open for enemy attacks and blocking your way at the same time. Especially the bats in Dracula’s mansion are horrible, because they fly around so haphazardly that it’s near impossible to reliably hit them. Early on you can find a gun, which you’d expect to be the perfect way to keep out of harm’s way, but it does not actually work as a ranged weapon and is therefore near useless.

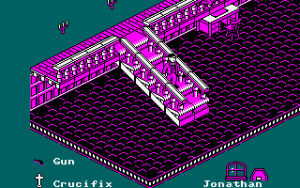

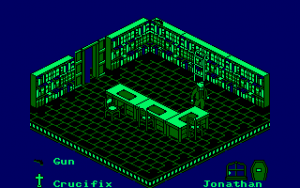

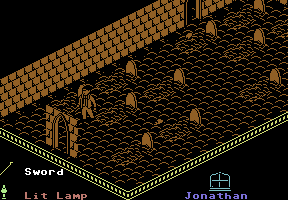

The game is divided into two chapters, which even have to be loaded separately, depending on the platform. In the first part Jonathan Harker finds himself within Dracula’s mansion and needs to escape. The mansion is huge with lots of rooms to explore, and Harker can even go into the cellar to check out Dracula’s coffin, but he has to find a lamp and a means to light it first. Technically you’re also supposed to find the deed to Dracula’s would-be house in Wismar, but all that is not even necessary. All Jonathan really has to do is find the keys and get out, which takes less than five minutes even within the slow engine. And that’s for the better, really, as it’s virtually impossible to get past all those bats in the cellar alive.

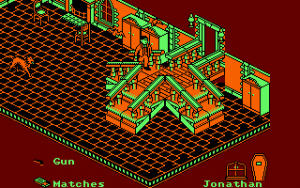

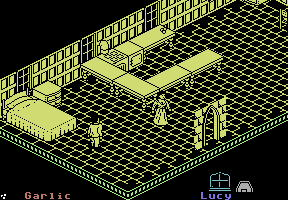

Part two takes place in the town of Wismar, where Dracula is running loose now. For an old home computer game, the place is bustling with people and plague-infested rats. You can switch between three characters: Jonathan, Lucy and Van Helsing. The two men are exactly the same except for their name – even their sprites are identical. It’s their task to find axes, cut down chairs into stakes and impale any villagers that have been turned into vampires. The only way to identify them is getting next to them and let them bite the current character, but since normal villagers cannot be killed it’s save to just attack anyone. All this is just a support for Lucy’s mission: To lure Dracula into her bedroom, to make him forget the rising sun and die like in the movie. (Here it’s just a “you win” type text message.) However, when there is a vampire in the next screen, the Count won’t follow there for some reason, so Jonathan and Van Helsing have to clear the way first. Oh, and anyone who is touched by Dracula dies instantly.

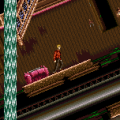

The monochrome display in theory would have offered an optimal incentive to imitate the tinted image of the 1922 silent movie (even though the game is based on the remake), but colors are just used randomly to distinguish the different rooms. The Commodore 64 port looks disappointingly identical to the ZX Spectrum original, only with paler colors. The Amstrad CPC adds a thir color per screen, which allows for some neat effects with the changing daytimes, which despite the vampire theme are not used for any gameplay significance. Dracula just runs around in the open any time of the day. There are some questionable combinations, though – orange and mint green?

A neat feature of these old UK adventures is the rudimentary physics engine, which allows to push around certain objects around the rooms and have them interact with other things, but in this game it is hardly used for anything, as all you can manipulate are chairs and ladders. There is no scrolling in either version, instead the screen just “flips” when reaching an invisible border, which can be disorienting when walking upwards where the content of the next screen is already displayed. Unless there’s a door in sight, there’s also no way of telling beforehand whether or not a room will end or go on further to the lower directions. The “music” is also just an annoying five second loop, and ranges from obnoxious scratching on the Spectrum to obnoxious bleeping on the Commodore 64.

Nosferatu the Vampyre has the disadvantage of being a video game adaption of a movie made in a time when games were in no place to emulate any kind of cinematic experience. It could have been worse – most licensed games in the 8-bit days were just pointless platformers and beat-em-ups – but even a decent text adventure would have done the movie more justice. It’s also incredibly short, and much of the second chapter is just the busywork of finding more chairs to cut into stakes, which for some reason doesn’t even work with all chairs.

Screenshot Comparisons