- Die Hard (C64 / IBM PC)

- Die Hard (NES)

This article comes courtesy of Cassidy from the Bad Game Hall of Game, do check them out!

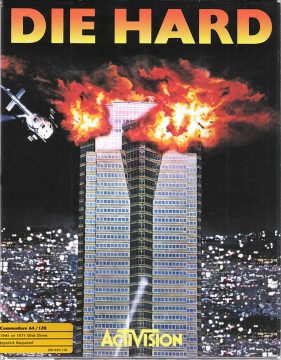

With the debut of Die Hard in theaters on July 20th, 1988, the potential for video game adaptation was immediately apparent. The publisher who would pony up the most cash to pay the licensing fee would end up being Activision, who immediately set about commissioning an MS-DOS / IBM PC reimagining of the action film du jour. The developers to answer the call would be Dynamix Inc. – they of Arcticfox and MechWarrior fame. Shortly following the completion and release of their Die Hard game by 1989, Activision would further call for conversions of it to the Commodore 64, as well as a completely different game for the Nintendo Entertainment System, with the latter effort resulting in perhaps one of the most “infamous” titles for the cartridge-based console. A fourth version was released solely in Japan for the PC Engine, though it’s really just an Ikari Warriors-style run-and-gun that has very little to do with the movie.

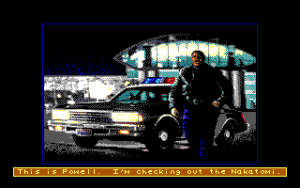

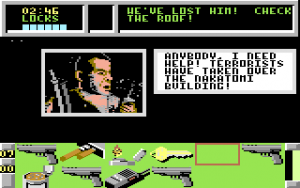

The IBM PC, C64, and NES versions of the game follow the plot of the movie – to an almost slavish extent, even. You play as Detective Lt. John McClane: A loose cannon cop from the NYPD who can’t help but get stuck in the wrong places at the wrong times. As per the events of the film, he finds himself trapped in L.A.’s Nakatomi Plaza while it is under siege by a team of Euroterrorists, as lead by the charismatic and cold-blooded Hans Gruber. It’s up to John to stop their plot, rescue a group of hostages (including his wife, Holly), and save Christmas for the sake of all the children of the world. It’s a good thing for the good guys that McClane is a master of guerilla warfare, with the wits and will to thwart this band of business-class baddies.

John’s tactics and improvised equipment translate into the games as items to be looted from enemies, and elements in the environment that you can interact with; from lighters and power cords, to fire hoses and bathroom first aid kits. In an example of an in-game opportunity ripped straight from the movie: In the PC and C64 versions, you can acquire the components needed to drop a bomb down an elevator shaft, wrapping a power cord around plastic explosives and using a detonator to set it all off. In seeking out the specific goons carrying these three items, you can effectively save yourself having to deal with a handful of enemies that would otherwise appear later in the game should they go un-exploded. This and several similar opportunities (picking up a radio to contact the LAPD, snagging a key used to open some locked doors, et cetera) are presented as an entirely optional tasks for you to consider completing. You’ll have to weigh the risk of pursuing these “side quests” against the benefits they’ll provide you in the later game. And depending on which version of the game you’re playing, these can either prove fruitful or frivolous.

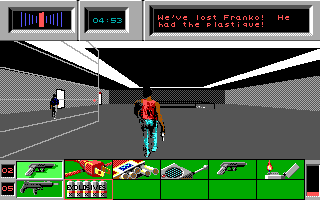

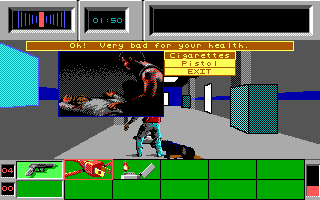

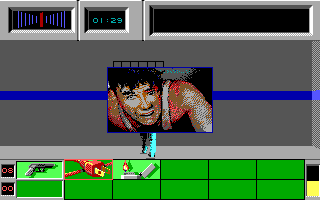

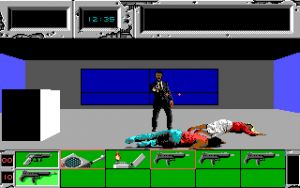

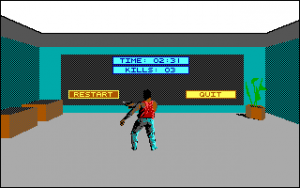

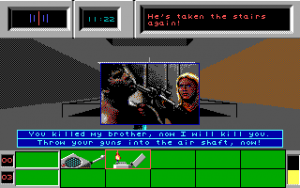

The original IBM PC / MS-DOS release has a behind-the-back third-person perspective and digitized character graphics, with players being dropped into a 3D raycasted game world; the presentation is fairly forward-thinking for a 1989 title. You’ll even occasionally be treated to digitized frames from the film, with Bruce Willis’ likeness altered in sometimes grotesque fashion (presumably to avoid some actor contract breach). Unfortunately, it’s hard to call much of any of this particularly “appealing” to actually look at, owing to some garish color choices and occasionally disorienting scaling / dithering effects. While the game does make efforts to mitigate some of the flaws of early 3D gaming – such as arranging scenery and prop objects to serve as landmarks in otherwise identical rooms – so much of the game ends up feeling like walking down the same grey hallway a hundred times over, all while stuck staring at the backside of a John McClane closer resembling Southside Jim from Pit-Fighter. (Kudos to one @DeathPuppy3 on Twitter for this incredibly apt comparison)

The next issue you’ll end up running into is in controlling our intrepid off-duty officer, between unintuitive keyboard commands and incredibly particular joystick operation. Effectively, there are three “modes” of control to contend with and alternate between: “Walking,” “Fighting,” and “Aiming,” as described in the manual. As you might expect, walking is primarily how you’ll navigate the Nakatomi building; moving in forward / backward direction while able to strafe across the width of the screen, and turning by holding the Shift key in conjunction with pressing an arrow key or numpad button. Given the primitive nature of the 3D rendering and perspective here, it’s about as clunky as you might imagine. This mode also allows for you to interact with scenery (including maps and first-aid kits) and to loot the corpses of fallen foes – otherwise inaccessible while in one of the combat stances.

When it comes to fighting, you’ll need to find an enemy actually willing to engage in melee, whether they be unarmed to begin with or expend their ammo supply (leaving emptied guns to be uselessly looted). Once you’re in proper position and proximity, you can press the spacebar to engage in a melee mechanic wherein you’re expected to read tells by your enemy and respond with one of three attacks or four defensive maneuvers. In actual execution, the game running at it’s intended full speed makes reading these tells a nearly impossible feat, and can quickly lead to your being pummeled by the most pathetic of enemies. If you want to survive melee encounters as unscathed as possible, rapidly alternate between your forward kick and punch, and hope that your opponent fails to answer for it.

Switching to shooting, you can select either a handgun or Uzi and enter into stance where you swing your arm from side to side of the screen to aim. However, given the limited frames of animation and the fact that John’s sprite obfuscates enemies in front of him, you’re very liable to waste your precious ammo. At the same time, standing still to line up your shots leaves you vulnerable to any incoming enemy fire, which has the nasty habit of briefly stunning you and rapidly draining your health. As such, fights are to be avoided whenever possible – lest you lose precious time, health, and ammunition. This is particularly unfortunate considering that each enemy in the game has unique levels of combat expertise (as well as unique appearances), to where you get a real sense of individualism for each of the custom-tailored mooks.

The game’s biggest problem comes down to its deliberate scarcity of goods, to where a second’s delay / damage received in a given fight or wasting one too many bullets can spell inevitable disaster for your run. Between the rarity of healing items and the possibility for baddies to attack you on the first frame of entering a new room; your health is likely to run in the red for the bulk of the game, and death will always be one inopportune moment of clunky control away. It’s a shame, too; as despite its myriad flaws, the IBM PC Die Hard is an admirably ambitious title with a ton of potential behind it. While the developers at Dynamix perhaps oversold themselves by claiming to have “developed an entirely new form of 3-dimensional technology,” their efforts are still to be commended – flawed as the execution may ultimately be.

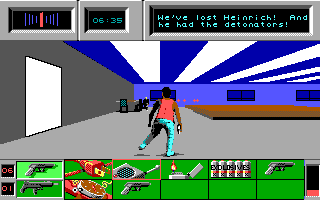

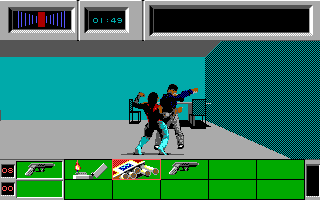

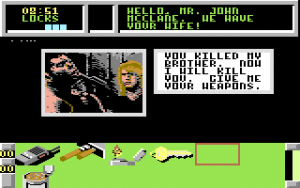

It’s with the conversion to C64 by Silent Software that Die Hard really begins to take shape. Ditching the 3D and behind-the-back perspective gimmickry, the game instead offers a profile view of the action, making the melee component of combat feel more akin to a beat-em-up. Not a particularly good beat-em-up, mind you, as combat is still a test of rapid alternating / mashing two moves. But on the plus side, this also means that firing your gun is as simple as lining McClane up vertically and firing away. You’ll even be treated to a view of enemy health bars, so you’ll know exactly when you’re hitting and missing. This all has the cumulative effect of making combat more bearable, and encouraging a gun-forward approach where you can quickly shoot terrorists dead and grab immediate replenishments of ammo off their corpses. While this might diminish the sense of scrappy survival that its predecessor aimed for, it still makes for an entirely more accessible game by comparison.

If there’s one major “downside” to this conversion, it’s the fact that navigating the halls of the Nakatomi building can be somewhat confused by the perspective. In following roughly the same floor layouts as seen in the PC game, but removing door breaks from some of the longer stretches of hallway (as well as dropping the ability to turn in four directions), you may have to more frequently consult maps to figure out exactly where you are. Another nitpick comes with your guns no longer automatically dropping / swapping when you empty their magazines, occasionally leaving you frantically selecting a new gun from your inventory while under fire. But putting these gripes aside, the C64 conversion still serves as a better realization of the PC release’s gameplay mechanics, by translating them to a more functional perspective and easing up on the outright unfair difficulty of the original.

Screenshot Comparisons