To talk about Devil May Cry, we first have to talk about Resident Evil 4. It had probably one of the rockiest development cycles in Capcom’s history, going through four different versions before finally coming out as the masterpiece it is today. The first of those versions, started in 1999, was based around a man named Tony who had abnormal abilities with a major action bent over actual horror. You can thank Hideki Kamiya, known tweeter and game designer, for this. He changed the project’s theme to “coolness,” resulting in a very strange game that had elements of Resident Evil body horror (and possibly painted a member of the Spencer family as some sort of superhuman European lord, based on some concept art) and awesome looking shooting and swordplay. Shinji Mikami, the main guy behind the franchise, realized this didn’t fit well with the series, so he let Kamiya and his team turn it into an original work. From there, Kamiya changed bio curses to demons, used The Divine Comedy for making new name conventions, and changed the entire combat system after seeing a bug in Onimusha that made it possible to launch an enemy in the air and juggle them.

The result of all these shenanigans and indulgences was the birth of an entire genre: Character Action. The idea behind a character action game is to mix together fighting game inputs and mechanical complexity with a beat-em-up or hack-and-slash structure. 3D action games were already headed in this direction for awhile, but it took years for people to figure out what they could really do with analog sticks during the PS1 and N64 era. Until Devil May Cry, most 3D action games focused on transplanting old genres into a third dimension without really asking what new possibilities that entailed.

Kamiya and his team seemed to pin things down, ironically by looking at bugs in their projects and going “hey, that was pretty cool.” Devil May Cry‘s big innovations, besides applying air combat and juggling to a 3D setting outside a fighting game’s limitations, come down to making you learn and become familiar with your character to succeed, and not just simply engage with basic mechanics. Think of it like this: In Castlevania, the series eventually created new characters with different styles of play, but they all stayed fairly close to the base Simon Belmont controls – a melee attack, a walk, subweapons you can find around the area, and a ridged jump. It’s all the basics of the genre it plays in, with a variety of variations overtime. The mechanical depth of those variations was ultimately minimal, as the point was to make a new challenge for getting through obstacles on a 2D plane.

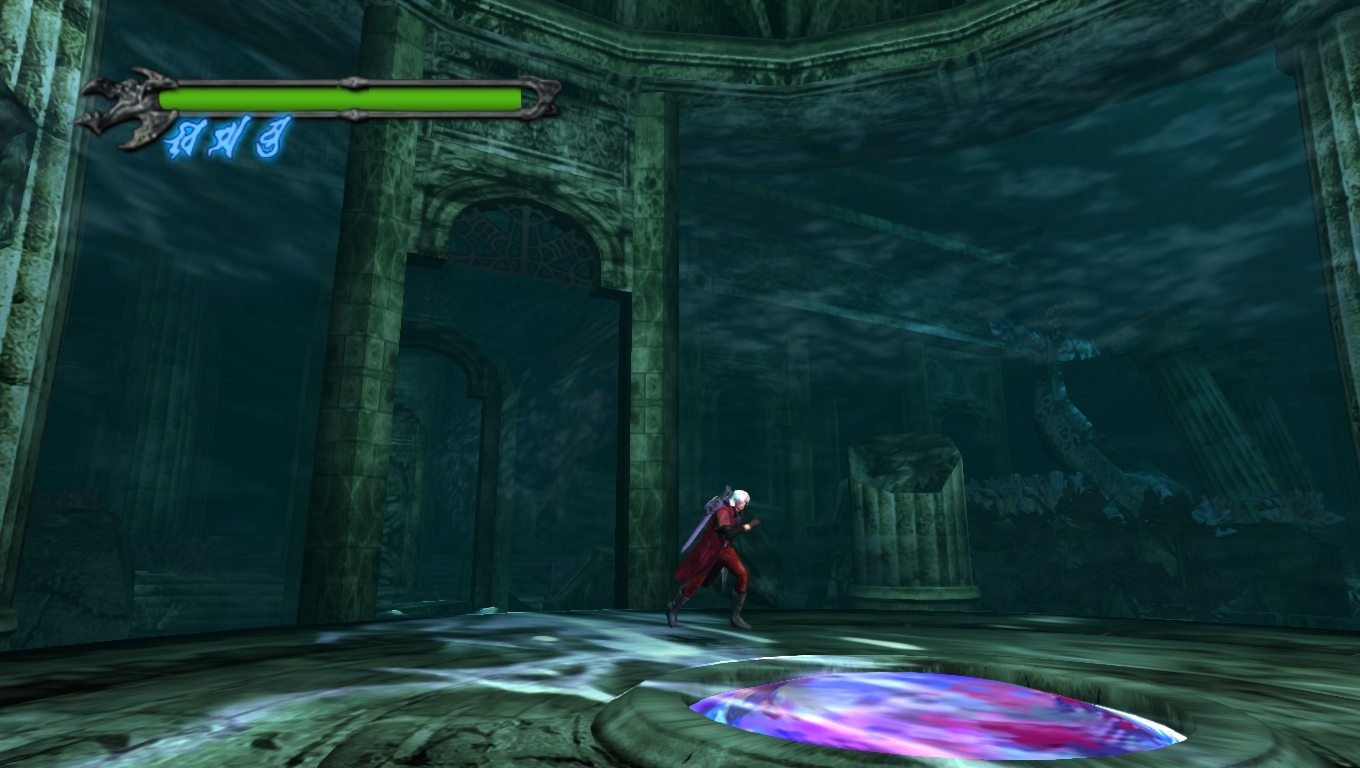

Devil May Cry has a similar foundation, but Dante controls completely different from anyone else in the action game world up to that point. You have to take into account where he’s facing to use a launcher of a special thrust attack. His Ifrit move set is based around charging up blows for big damage. His guns are meant to supplement his melee skills instead of being a style of attack of its own for particular situations. His skill set simply isn’t just for solving problems, treating enemies as obstacles in the terrain or stuff to take down to progress, but as a way for the player to express themselves mechanically. Everyone who plays Devil May Cry plays it differently. The third dimension introduced a new layer of freedom 2D games didn’t have, because you weren’t traveling just one plane. You weren’t just getting from point A to B through the mechanics of the game anymore – actually playing with those mechanics could be fun in of itself. Thus, Devil May Cry has a more complicated combat system than most games of its kind, and that complexity created a system where no one playthrough would be the same as another. The game even encouraged this with the style system.

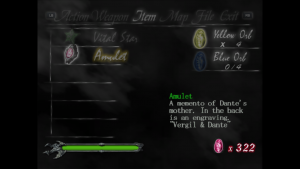

Like many action games from the era, Devil May Cry would grade you on how you did, using a mission based structure with a letter grade given at the end. Your performance was based on time to complete, collectibles found (the red orb currency), not having to use items to progress, damage taken, and most importantly, style points. As you fight enemies, sometimes a phrase will appear in the upper right portion of the screen, starting with D through A and sometimes S. This is your style rating, and at the end of the mission, your average style becomes a factor in your grade. Style also goes up in a way that goes against nearly all game design conventions at the time. Where most combat was for the sake of a player overcoming an obstacle, DMC goes one further and asks you to do it as cool as possible. Strike an enemy right before they hit you, use a wide array of moves in a short amount of time, make a risky charge attack and manage to hit with it for big damage, counter an enemy at the right time (a concept used only for sin and death scissors). Don’t just be efficient, show off. Turn the enemies into a canvas you paint on with your blades and bullets and hell-fire gauntlets as your brushes.

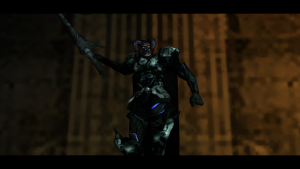

The game being so difficult also added to this effect. Accomplishing something in DMC, outside the encounters with death scissors and death scythes (DEVIL TRIGGER SHOTGUN SHOTGUN SHOTGUN SHOTGUN ectectect), feels truly earned, and many challenges will often teach you that experimenting with your movement and weapon options can open new doors that let you dominate truly deadly foes. This aspect of the game has aged poorly due to the limited experience everyone had with 3D design and the PS2 hardware at the time (especially the odd RE camera angles that never really left the franchise until Ninja Theory’s DmC), but there are still moments that fill you with a sense of satisfaction after a mess of frustration. The first boss Phantom is a great example, a magma spider only vulnerable around the head that actually blocks its weak point. He’s very difficult to new players, but he teaches the player to be patient, take advantage of opportunities, and pay attention to an enemy’s movements to learn how they function. It’s a solid mixture of old school sensibilities and new design ideas nobody had really done before, or at least so well.

DMC even makes a strong narrative structure for a franchise. Dante is one of the goofiest and most likable characters in gaming history, despite coming from a game series sold on awesome action and intense violence. He’s basically an all powerful superman who could do anything he wants, and that amounts to making bad puns and having fun fights with murderous demons. Dante shows off just for him and nobody else, a guy so comfortable doing what he likes that he becomes cool while being as uncool as humanly possible. The key to this is that Devil May Cry, as a franchise, is sincere to the point of ridiculous farce, and the best games find a solid balance between the more dramatic story beats and comical stylings of the pizza obsessed white haired bishonen who can take a bullet to the head and barely register it.

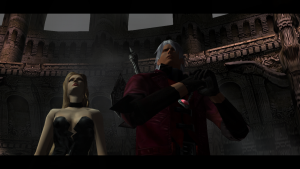

Unfortunately, Kamiya didn’t really nail down a good balance between wackiness and pathos here. The game starts off on a right foot with an absurd scene where Trish attacks Dante at his shop and Dante blows up a motor cycle in badly done slo-mo by shooting his handguns Ebony and Ivory as fast as a machine gun. Things slow down from there with some puns and general cockiness, and then starts showing qualities in Dante’s character that get abandoned later, particularly saying Dante’s moral code is based on trying to live up to his father, the demon Sparda who saved humanity. Mundus ends up being one of the most one note and dull villains in the whole series, despite having a massive impact on the entire franchise in Dante’s back story, and the ending goes so cheesy that it becomes painful and cringe enduing. The sincerity becomes too much, especially with the entire style of the game clashing wildly with the half-baked character arcs that were barely explored. And then there’s Trish….oh boy.

Trish manages to become a pretty fun character once she returns in 4, but she doesn’t get much screen-time here, and what she does get with Dante becomes instantly uncomfortable because she looks exactly like his dead mother. She is also set-up a bit to be his possible love interest. Yeah, the franchise abandoned this idea as hard as possible to the point that you’re not even sure if Dante even understands what sex is in 3 and on, but the implications here, especially with how she fits into the plot, is the sole truly bad idea in the game’s narrative.

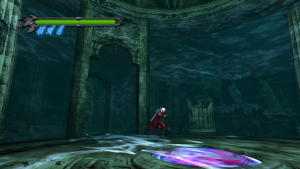

There are also a few bad ideas in the actual design to boot. While most of the enemies have brilliant patterns and attack styles, the otherwise super cool Frost enemies have one truly ridiculous move where they freeze themselves in a block of ice you can twiddle down, but it will ultimately melt and will have a truly unbelievable amount of invincibility frames on cool-down that last seconds in a game mostly known for speedy combat. Sometimes, they will repeat this move over and over, making a fight last far longer than it need to. It’s not fun. The aforementioned sin scissors are really fun once you figure out the timing to get a critical hit, but the death variants are just damage sponges with one truly annoying charge attack that’s hard to read at times due to the limited camera. Platforming segments are included, but Dante’s jump is awkward and not designed for platforming at all, and the scripted leaps he can make don’t always come out as you’d expect. There’s just a mess of these little issues that ruin some of the fun in the moment, the worst being the swimming segments.

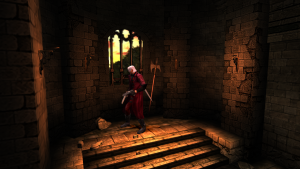

For some reason, there are points in the game where Dante goes underwater, which switches the perspective to first person. You can change where Dante is looking, then press a swim button to have him move forward. If you come across an enemy, you have to click the lock on down and then fire a dumb needle gun over and over once you get things lined up. Shoot until dead. There is a very minor strafe you won’t need. That’s it. That’s the whole structure of the segment. It’s not fun, but it’s not frustrating either. It’s just boring, a part in an action game trying to be exciting and failing miserably. It was still early in the sixth generation, and everyone was figuring out what worked, so this is a forgivable sin, especially because it doesn’t pop up much. However, that doesn’t change the fact it’s a major desert of engagement in an otherwise exciting and strong game.

The first Devil May Cry isn’t quite a masterpiece, but it may be one of the most important action games ever made. If it never existed, the entire concept of what an action game in 3D was would be wildly different. We’d probably wouldn’t have the likes of God of War, Darksiders, Furi, and countless others without it. It created a franchise with a devoted fanbase who have followed it endlessly for decades, becoming one of the defining titles of the PS2. There was a lot to live up to for a sequel, but Kamiya wouldn’t be around for it. Instead, a different director was assigned to the project…and he did so bad that he was replaced halfway through the project. It is with the next game that Hideaki Itsuno, who had worked on some of Capcom’s most beloved fighting games, entered the story with quite possibly the single most disastrous introduction one could ever imagine.

Note: Screenshots for Devil May Cry 1, 2, and 3 were taken from PC releases of the HD Collection. Said collection is fairly accurate to the original versions, but there are notable issues, such as FMVs being stretched out and some menu art not being scaled with the new wider screen support.