In March of 2012, two friends decided to make a game together. They finished it January 2013, and released it to the world the next month (with an Android point a few months later). That game is Anodyne, and it’s one of those games that almost defies all conventions and labels, yet sticks so close to established and effective formulas. It’s not unlike Undertale in that respect, even carrying some similar themes, but it chooses to focus on abstraction over blunt commentary, and that choice served it well.

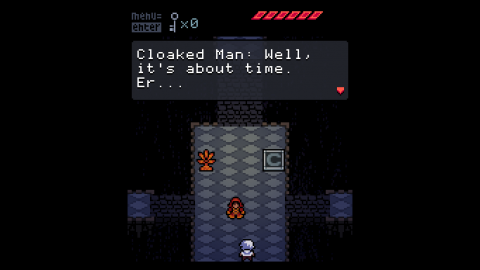

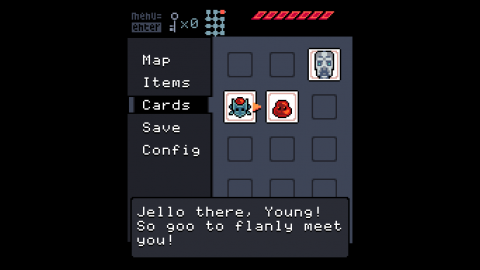

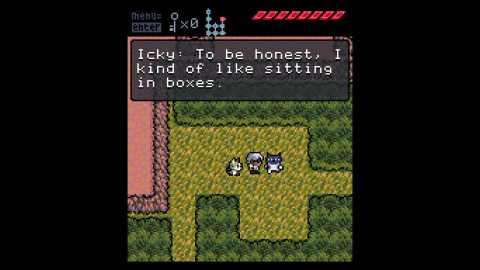

The story follows a white haired nerd named Young. We never hear his voice, but it’s unnecessary. You are guided by a mysterious sage, who instructs you to travel among various parts of the world within a time and space nexus littered with portals. The goal is to fully explore the strange realm, explore the six dungeons within, and collect cards that will eventually unlock a special gate that leads to the truth of the world and what Young’s role in it is. But things get very …odd. Some of the words from defeated bosses suggest some troubling things, and after you finish the main three dungeons and start up a windmill to unlock the other three, you start finding new areas that ignore the post-apocalypse/light fantasy theme of the rest of the game. The town of black and white, in particular…

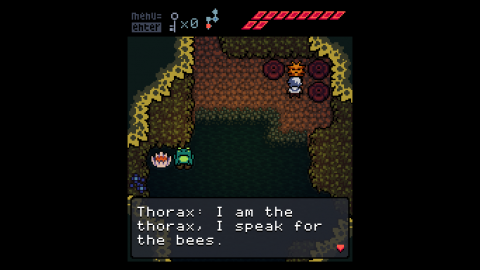

Anodyne takes place in a strange dream world, but also has moments of concrete theme work. All throughout the game, there’s a sense that there’s more to what’s presented, and the game starts to directly address at the halfway point, as you see strangely horrific events and settings and get more and more implications. Young is more than just a silent protagonist or player avatar, though his silence seems to be important to the game’s running theme of player behavior. It paints a complicated picture dressed in half-truths and unreliable narration that makes all of this questionable, but my own personal reading was that the sage was a developer and was trying to reach Young on an emotional level to help him grow in some way. That still doesn’t explain the sheer amount of strangeness in here, including the later three dungeons, which include what can only be described as an eldrich circus.

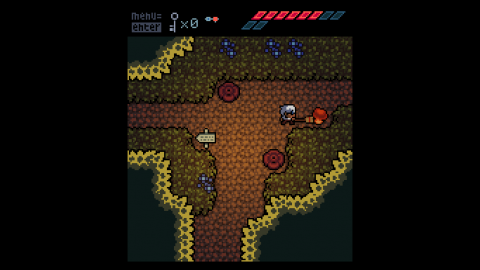

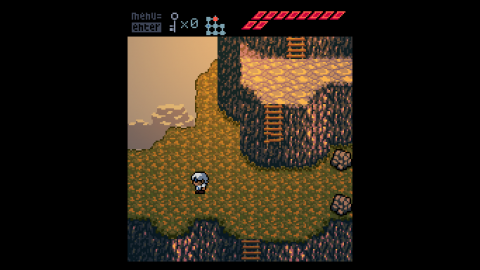

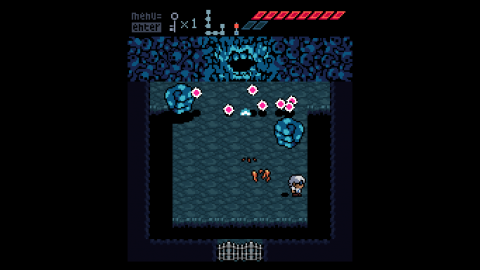

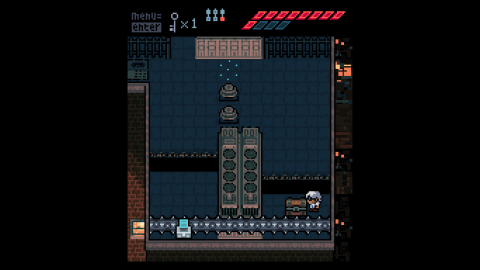

The game jumps from style to style, casting aside the ice/fire/water/ect level themes for after the end of the world, sci-fi horror, caverns, and twisted versions of various real world places. It has a sense of natural mystique and awe, but that slowly gives away and mixes with tragedy, horror, and confusion. There’s even an 8-bit maze with unkillable enemies in here, just to make sure you don’t regain a sense of normalcy. All the while, it keeps a lovely 16-bit graphical style, with a tall screen display that does a great job at accommodating all the areas and sprites. Said sprite work is solid, with a ton of imaginative enemies and creatures to find. There’s even demonic maids. No, really. They don’t like it when you do their job for them.

The game takes heavily from 2D Zelda games, but makes some significant changes. First, your weapon is not a sword, but a broom. It bashes baddies fine, but you can’t destroy or cut objects with it. However, you can sweep up dust, and then spread it back out to solve puzzles, like using the dust as a makeshift raft. Item hoarding is also removed entirely (and lampshaded for a joke at times), with maps littered with more mechanically simple puzzles and challenges, like taking out a group of enemies in an area or jumping around obstacles. This was one of the better design choices, as it cuts down massively on menu time and keeps the game speedy and addictive. No searching your inventory for an item to pass a point in a dungeon, just see the problem and figure it out with your own wits and skills.

The only place where the game suffers is the platforming. Once you get the jump boots, you’re introduced to a mess of jumping puzzles, and they range from perfectly fine to a living hell. Momentum is too strange and fast to really gauge properly, so you may end up going in a slightly wrong direction, or during the boost pad segments, blast off in completely unexpected directions. If it wasn’t for the Zelda-like respawn with minor damage after a pitfall design choice, the platforming could have seriously killed two thirds of the game, especially has it becomes more central in boss battles.

When all is said and done, though, where the game truly succeeds is atmosphere. It’s very easy to get lost in each area, all with not only their own special themes, but their own color schemes and effects. There are so many perfectly beautiful moments in the game, and some haunting ones as well. That aforementioned black and white town comes out of nowhere and feels like it came from a completely different game. It’s easily the strongest sequence of the game, but it never lets up as it goes on, especially in the ending segment. This world feels real, despite how absurd and nonsensical it can be. There’s real humanity in it, and some introspective thoughts delivered by a few characters. The talk with the girl about the skyline is especially memorable. Add in the fantastic score, an unorthodox and downplayed affair, and the end result is simply enchanting.

An amazing amount of things were done with so little, and you can tell the creators put their all into making this. There are few games quite as memorable and alive as Anodyne, despite the obnoxious platforming. It takes about eight to nine hours to complete the game, and it is time well spent. It commonly goes for ten dollars, and that is money well invested. This is a must for fans of the old-school Zelda games and the stranger releases from the days of the SNES. You know, your Soul Blazers and Live-A-Lives. Anodyne comes from that school of introspective games, and it deserves to be put in the same ranks as them.

Links:

Anodyne Official website