Kid Chameleon is an underrated action platformer from Sega’s early 90’s American development studio Sega Technical Institute, otherwise known for creating Comix Zone and Sonic Spinball. Most of the Genesis’ hit platformers made waves with hip anthropomorphic avatars and unique, dynamic mechanics that threw players into one crazy situation after the next. Based more off of traditional elements, Kid Chameleon comes across as old hat and is too often critically likened to an outdated Super Mario derivative without the wacky Japanese flair. What critics and gamers would not realize until much later was that, despite the fact that it lacked the unpredictable gimmicks of an Earthworm Jim or Battletoads, the graphical prowess of a Dynamite Headdy or a Vectorman, and the speed and instantly recognizable style of a Sparkster or a Sonic the Hedgehog, Kid Chameleon was one of the finest platforming experiences on the console. While not exactly bursting with originality, it expands mightily upon its borrowed concepts and refines them with a greater emphasis on skill and strategy than any of its contemporaries.

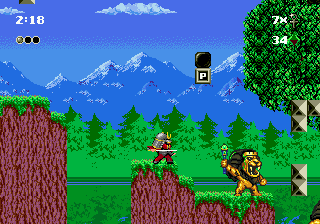

The coolest game in town.

One concept unborrowed from older games is Kid Chameleon‘s objective, which is remarkably ahead of its time. See, there’s this new walk-in arcade game in town called Wild Side, which acts like the holodeck from Star Trek in creating virtual worlds around the player. Everybody is playing it, but nobody is coming back out. Seems the boss of the game, regrettably named “Heady Metal,” has been capturing the losing players. That is until you come along, the Kid Chameleon. Despite what a surprising number of sites seem to suggest, the character’s name is not “Casey”: he’s only ever referred to as “Kid Chameleon” in the official literature and in-game text. Confusion seems to have arisen from a one-off spotlight strip in a Sonic the Hedgehog comic where the name Casey is used, which seems less like a canonical update than a play on the game’s title: “KC” as literally “Ca-sey.” For the sake of simplicity, let’s just call him the Kid for now. Anyway, to beat Kid Chameleon, you must help the Kid to beat Wild Side: in essence, to beat the game you must beat the game. It’s the kind of disposable meta-plot you’d expect to find in a simpler modern home-brew title than in an otherwise complex early 90’s console platformer. But let’s face it, these aren’t exactly the kinds of games that are played for their narrative merits in the first place.

If a blunt appraisal of Kid Chameleon is required, it could be said that it binds the fundamentals of Super Mario Bros. 3 sans overworld map (and with a level warp system based on earlier titles in that series, taken to logical extremes) with the scoring/extend system of Sonic the Hedgehog. Your player character runs/walks their way through a challenging stage composed of a variety of unusual tiles and filled with a motley assortment of colorful enemies to pounce upon in an attempt to reach either the end-level flag or an appropriate warp platform. Along the way, power-up blocks (both visible and hidden) can be broken open with a jump to reveal their contents. Usually this will yield relatively non-useful trinkets (that serve a purpose when you acquire enough of them), but often enough you can gain a power-up that will alter your physical appearance and abilities. Sound familiar? The control scheme is also set up pretty similarly, with one button designated for running, one for jumping, and one for a power-up specific special command (when applicable). As with many Genesis titles, these are assignable in the options menu, where there’s also the very thoughtful Fast Play option to make running the default. Toggling this, the third button essentially becomes a “walk” button you’ll almost never use, since quick reflexes are nigh indispensable in Kid Chameleon. Running has a slightly different feel to it due to a slight acceleration delay, but otherwise, if you’ve played a 2D Super Mario title, you’ve got the gist of this game. Still, Kid Chameleon remixes the old formula by expanding the number of power-up helmets to nine and making their use much more essential to survival and progression:

Transformations

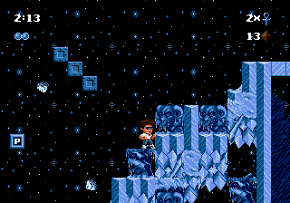

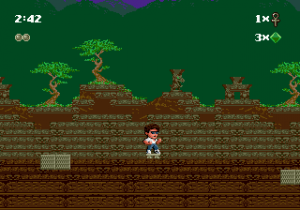

Kid Chameleon

The one Kid too tough to beat. You begin every new life without a helmet, leaving you vulnerable until you find one. In this form, the Kid has no special powers, but he can perform a quick flip up to ledges just out of his reach.

Iron Knight

The Iron Knight is slow and heavy, so heavy that he can break desctructible blocks just by landing on them, which can help or hinder your progress depending on the situation. He also sports five hit points, the most of any helmet, and can scale sheer walls from the ground up.

The Iron Knight is slow and heavy, so heavy that he can break desctructible blocks just by landing on them, which can help or hinder your progress depending on the situation. He also sports five hit points, the most of any helmet, and can scale sheer walls from the ground up.

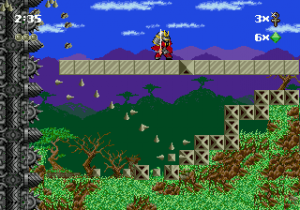

Red Stealth

Red Stealth is one of the more versatile power-ups in Kid Chameleon. With it, the Kid can run faster and jump higher than with any other helmet, not to mention attack with his samurai sword, though he can only swing it while grounded. In the air, he can use the sword to break blocks beneath him.

Red Stealth is one of the more versatile power-ups in Kid Chameleon. With it, the Kid can run faster and jump higher than with any other helmet, not to mention attack with his samurai sword, though he can only swing it while grounded. In the air, he can use the sword to break blocks beneath him.

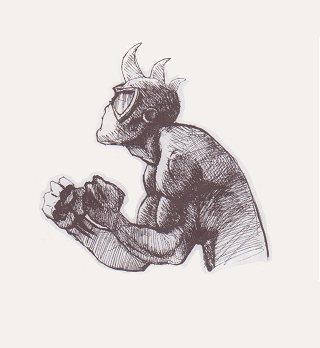

Berzerker

The rhino-like Berzerker helmet lets the Kid attack with a spiked headbutt. This can be used to charge through enemies, but more importantly, the Berzerker can bust through walls, including otherwise impassable steel barriers. You need to run a few paces before he’ll lower his head though, so using him in close quarters can be awkward.

The rhino-like Berzerker helmet lets the Kid attack with a spiked headbutt. This can be used to charge through enemies, but more importantly, the Berzerker can bust through walls, including otherwise impassable steel barriers. You need to run a few paces before he’ll lower his head though, so using him in close quarters can be awkward.

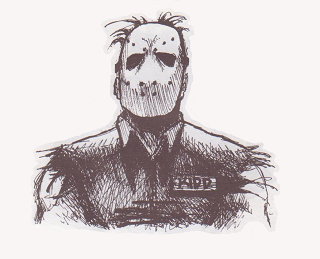

Maniaxe

One of the more effective offensive helmets, the Maniaxe has the ability to throw axes, enabling you to defeat enemies from a distance (including some that could not be killed otherwise) and making him the de facto choice for most of the boss fights. Looks suspiciously like Rick from Splatterhouse.

One of the more effective offensive helmets, the Maniaxe has the ability to throw axes, enabling you to defeat enemies from a distance (including some that could not be killed otherwise) and making him the de facto choice for most of the boss fights. Looks suspiciously like Rick from Splatterhouse.

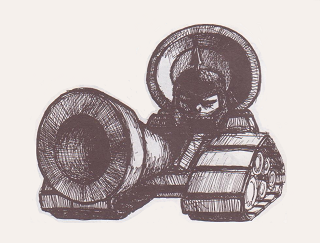

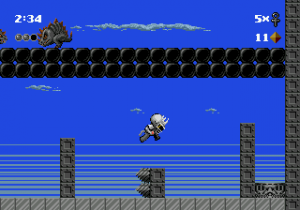

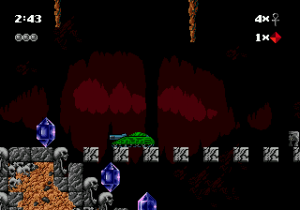

Juggernaut

Easily the coolest looking helmet, the Juggernaut is a crazy low-profile skull tank. With it you can spam bouncing skull bombs and blow through just about any opposition. The Juggernaut is wider than most transformations, which can prevent it from entering certain passages. It can also auto-duck certain projectiles, but cannot ascend inclines.

Easily the coolest looking helmet, the Juggernaut is a crazy low-profile skull tank. With it you can spam bouncing skull bombs and blow through just about any opposition. The Juggernaut is wider than most transformations, which can prevent it from entering certain passages. It can also auto-duck certain projectiles, but cannot ascend inclines.

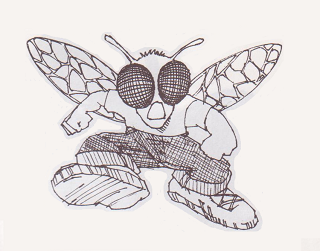

Micromax

The Micromax helmet transforms the Kid into a small human fly that can easily enter spaces that are otherwise inaccessible. He also gains the ability to wall-jump. Eat your heart out, Super Meat Boy.

The Micromax helmet transforms the Kid into a small human fly that can easily enter spaces that are otherwise inaccessible. He also gains the ability to wall-jump. Eat your heart out, Super Meat Boy.

EyeClops

One of the more peculiar accessories, the EyeClops helmet gives you a ray gun which reveals any invisible blocks in the path of its beam for a few seconds. This makes it invaluable for finding hidden paths and items, but the revealed blocks can also destroy enemies occupying the same space.

One of the more peculiar accessories, the EyeClops helmet gives you a ray gun which reveals any invisible blocks in the path of its beam for a few seconds. This makes it invaluable for finding hidden paths and items, but the revealed blocks can also destroy enemies occupying the same space.

Skycutter

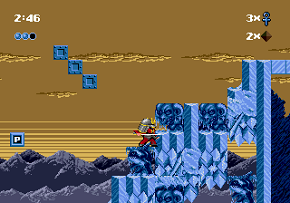

The Skycutter is an ultra-quick hoverboard that can reverse gravity and ride on the ceiling. It’s also wider than most transformations (though not as wide as the Juggernaut), making it a simple choice for traversing patchy terrain. Unfortunately, the Skycutter is constantly in motion and, like the Juggernaut, it sucks on inclines, making the Skycutter rarely useful outside of the sections designed for it.

The Skycutter is an ultra-quick hoverboard that can reverse gravity and ride on the ceiling. It’s also wider than most transformations (though not as wide as the Juggernaut), making it a simple choice for traversing patchy terrain. Unfortunately, the Skycutter is constantly in motion and, like the Juggernaut, it sucks on inclines, making the Skycutter rarely useful outside of the sections designed for it.

Cyclone

The Cyclone helmet imbues the Kid with the useful ability of unlimited flight simply by jamming on the Special button. As can be expected, it is game-breakingly awesome the longer you can hold on to it, making child’s play of many of the tougher later stages.

The Cyclone helmet imbues the Kid with the useful ability of unlimited flight simply by jamming on the Special button. As can be expected, it is game-breakingly awesome the longer you can hold on to it, making child’s play of many of the tougher later stages.

As the Kid begins each life with only two hit points that can’t be replaced except when returning from a defeated transformation (again, think Mario’s third), much of your play time will be spent wearing helmets or actively seeking them out, if only for the extra hit points. Occasionally the game will force your hand, requiring you to use a specific helmet to surpass certain obstacles (usually involving helmets of the climbing/flying/breaking stuff variety). In these circumstances, the helmet you need will always be provided somewhere nearby, though not always in plain sight. But most levels will offer a choice between a few different helmets, leaving it up to the player to decide which of those at their disposal is most appropriate for the situation and often providing varying paths depending on that choice.

This becomes a major part of game strategy as the player progresses beyond the first few levels: Kid Chameleon rewards the player for having the right helmet at the right time. The player can not only gain in-level rewards by finding a path that leads to 1-Ups, but also inter-level rewards by surviving long enough in a certain transformation to access secrets in later levels. Want to clear the Isle of the Lion Lord in under ten seconds and/or skip over a dozen levels from there? Find a Cyclone helmet and keep it til then. Want to beat The Whispering Woods II in even less time than that? Bring a Berserker. Having a tough time in Devil’s Marsh II? It’s easy if you have a Red Stealth, although you won’t find a single one in that level. While Kid Chameleon’s difficulty can initially seem daunting, the more the game is played and its secrets are unearthed, the more fair it reveals itself to be.

But even with the reasonable quantity of helmets per level and abundance of hit points that come with them, survival in Kid Chameleon is still a challenge. While your early opposition consists of mostly benign stomp-fodder like the dragons and rock tanks of the first two levels, later levels pile on the enemy forces and you won’t be able to go a few steps without being accosted by crazy anthropomorphic killer whales, seemingly indestructible scorpions, instant-spawning demon heads, aliens and other allsorts. Some of these are just plain silly looking, but most are cleverly animated: creatures like the seemingly-cliché dripping slime that quickly coalesces into a sentient blob and the docile alien walkers that burst into flames and manically (but harmlessly) flail around after you’ve defeated them, these take the cake.

To compensate a bit for these odds, Kid Chameleon does offer the player a few breaks in the form of diamond powers and the generous extend system. 90% of the power-up blocks you’ll break will contain diamonds, whose color will vary per level despite the fact that only their quantity is important. Unlike Mario’s coins, these max out at 99 and aren’t exchanged for a 1-Up. Instead, the Kid can activate special diamond powers (by pressing the run/walk and start buttons simultaneously) which vary depending on how many he currently has (typically “over 20” and “over 50” are thresholds) and which transformation he’s currently using. Most of these consist of some sort of diamond barrier attack that will let you blaze through enemies for a few seconds. Some, specifically the EyeClops and Juggernaut helmets, have special low-cost diamond powers that alter their main special attack. Others are more interesting: the Iron Knight can gain you a semi-permanent extra hit point, for instance, while some others can slow down enemies, provide temporary invincibility, or simply grant an extra life on the spot. Because diamond-hunting can be slow and tedious, you probably won’t use these powers too often: on the whole, they feel like they were kinda tacked on to give less skilled players a fighting chance. Still, they can get you out of a jam, and it’s often feasible to wander off the beaten path collecting diamonds for a while to save up for a particularly treacherous upcoming segment.

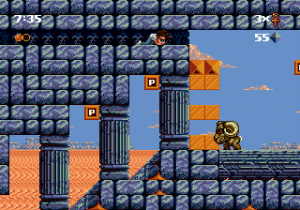

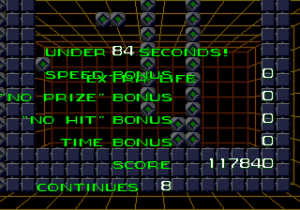

The other nice thing about Kid Chameleon is the fact that the game will throw extra lives at you like they’re going out of style. Lives and continues (essentially 3-Ups) can be found in certain P-blocks as ankhs and coins respectively, but extra lives can also be earned simply by performing well in the levels. Finishing any stage by its normal flag exit will bring up a tally screen kind of like that of Sonic the Hedgehog, where the player can earn bonus points based on how quickly they completed the level, as well as more elite bonuses such as no-hit, no-helmet, and best path bonuses. In this sense, high-level players can try and tackle Kid Chameleon for score or attempt speedruns, both of which the game seems to encourage despite the fact that merely completing the game in one sitting is an achievement.

While the novel implementation of the power-up helmets is certainly a big part of Kid Chameleon’s charm, its enduring difficulty stems from its most memorable feature: its labyrinthine level tree. See, most levels can be completed simply by touching the end-level flag, bringing up the tally screen and introducing the next level with the appropriate title screen. However, you won’t have to journey deep into the game before you start finding warp platforms that, when stood upon, can transport you (sometimes literally) elsewhere. In a flash, you could be on the other side of a level, a stage ahead, a stage behind, or a dozen away from where you just were, who knows? Since there’s no introductory screen to tell you where you’ve arrived, you’ll only know where you’ve ended up by losing a life or reaching the end-level flag (if one is present). In a few isolated cases, you can even get caught in a loop between two levels or within a single level until you find the right warp to progress forward. Naturally, this can make navigating the game a bit confusing until you’ve tried struggling through it several times.

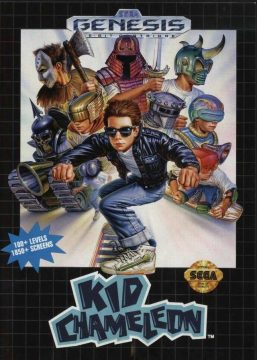

Any owners of the original American box art will tell you that Kid Chameleon proudly declares this feature, claiming 100+ levels in-game, though this isn’t entirely truthful. The game is loosely divided into four chapter segments consisting of about sixteen levels each and concluding with a boss level. Additionally there are about 32 mini-levels only accessible by warp platform that are referred to as simply “Elsewhere” and only consist of a couple of screens worth of obstacles. Early chapters tend to be mostly linear, with a handful of Elsewhere asides and a few alternate paths to explore. Later in the game, things start to get out of hand, with Elsewhere paths galore and numerous difficult branches as Wild Side throws out all stops to arrest your progress. Herein lies the other major strategic element to Kid Chameleon: as you gain familiarity with the level tree, you can decide which levels to attempt and which ones to pass over. The versatility of this is much broader than is initially apparent: in reality, there’s only a handful of levels that you have to visit. Excluding the first five or so and about half a dozen or so key challenging ones in the final chapter, if there are a certain few levels you absolutely can’t stand to struggle against, there’s probably a way you can get around them, you just have to find it.

But be forewarned: there’s usually a trade-off for taking the easy way out, and avoiding one excruciating level may leave you destined for another. For instance, there are two major chapter-destroying warps hidden in the first half of the game: one skips most of the first chapter (including the boss!) but if you take it, you cannot take the one that skips about half of the second and third chapters (again, boss included). However, if you take that second warp, you’ll be put onto a path that requires you to complete the infamously difficult Bloody Swamp, which you might not encounter by sticking to the normal path. These branches become so complicated that not only do you only have to play through about half of the game’s 100+ levels, there are many you may not ever discover even after several playthroughs. The developers went so warp-crazy that there’s even a pair of obtuse secrets warps accessible by alternate methods, the first of which will skip basically the entire game and throw you straight into the last boss level, presumably so the unskilled can get some sense of achievement by seeing the unceremoniously brief single-screen epilogue (though it leads into an admittedly cool portrait gallery of the developers in sprite form). But Kid Chameleon is not meant to be played for its plot or its ending: it’s about the voyage, and there’s countless hours to be had pathfinding and exploring all the optional levels.

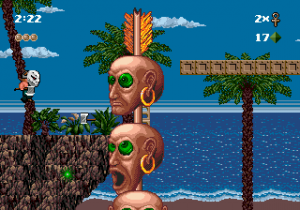

Not just interesting because of their unusual arrangement, the levels themselves are often particularly memorable in their own right. Certain major publications feature “retro reviews” that might try and tell you otherwise (revealing just how little time those reviewers spent with the game), but Kid Chameleon’s perilous level designs are hallmarks of the tile-based style and should be a point of reference for indie platformers to learn from. Each level falls into one of a myriad of themes, from forests and caves to cities, tropical islands, snowy mountaintops, and pyramids, all familiar video game tropes fitting with the game within a game plotline. These are encountered in no particular order and you won’t typically see the same setting more than twice in a row, Wild Side revelling in transporting you randomly about. Graphically, Kid Chameleon isn’t among the Genesis’ finest achievements, but its levels look fairly nice, usually sporting vibrant colors and a few layers of parallax scrolling. But aside from a particular look, the themes are not easily distinguished by their enemies, layout, special tiles, or platforming challenges: any variety of which could appear in any given level. Only the music tends to correllate (though not strictly), with a tropical theme for the beach levels, a funk soundtrack for the urban ones, and some heavy metal dissonance for the underground stages. Once again, the game’s soundtrack doesn’t usually rank in anybody’s top ten, but the tunes are varied and typically pretty catchy and some of the sound effects are memorable, particularly the maniacal laughing and digi-spoken “Die!,” which you’ll probably end up hearing a lot.

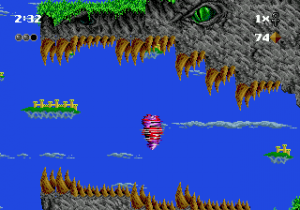

Anyway, the levels generally vary wildly in their layouts and challenges. Some are horizontally or vertically oriented, while others are wide open for exploration. Some are straightforward enemy gauntlets, others require painstaking platforming. Some are quick and nearly helmet-free, others are long and treacherous, requiring more than the three minutes allotted to complete the level and where the occasional time-extending clock power-ups are no longer an optional pickup. All feature an elaborate disbursement of interesting tiles, some of which can be moved about, others can be destroyed, disappear beneath your feet, fire out thorns upon activation, act as springboards, or even spout drills when you approach. These are arranged in increasingly challenging configurations as you progress, ensuring that the Kid’s adventure is never dull. And though the game generally focuses upon its core concepts in favor of gimmickry, there are a few unexpected surprises that show up from time to time, including sudden hailstorms that will stir up a few seconds into certain seemingly innocuous levels to quicken the pace and the equally unannounced “murder walls” that will incite a harrowing chase sequence that few games of the style have matched in terror or intensity.

There’s really only two things that could have improved the gaming experience, and both are unusual oversights for the era in which Kid Chameleon was made. Firstly, for a game as fast-paced and exciting as this, the boss fights are boring and tedious. All take place against a varying incarnation of “Heady Metal,” who takes the form of a couple of weird disembodied heads that float randomly around the screen spewing projectiles. Unless you have a transformation that can return fire, the only way to damage the boss is to jump on its heads a whole bunch of times. Considering the large number of hits needed to destroy the heads, their tendency to hang out near the top of the screen (which is a hard limit in Kid Chameleon), and the poorly-tuned hit detection that often leads to clipping through the boss sprite and taking contact damage, these boss fights are the least enjoyable part of the game by far. The only other thing that would have been nice was some kind of a save function. Considering the number of levels and the frequency of death, players will spend a lot of time in the first several levels and have difficulty acquiring experience with the later ones, especially since a single winning playthrough can take several hours in one sitting. This is yet again comparable to Super Mario 3, especially in that this time is compounded when playing with two players alternating turns. Something as simple as passwords to start at each chapter would have made a world of difference.

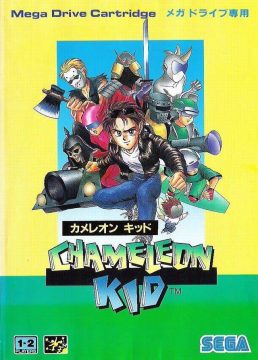

As for versions, there’s really only one. Regional differences are limited to the game title and box art, where the Japanese get a cool manga-style arrangement of the West’s more accurate but less enticing portrayal of the Kid’s alter-egos. The original version is hardly rare, but those lacking an original system will be happy to know that the game was accurately ported to a number of recent-gen platforms in one of many compilations arriving in the wake of Sega’s abrupt exit from the console market in the early 2000’s. These include the Sega Smash Pack 2 for Windows PC, the Sega Genesis Collection for the PS2/PSP, and Sonic’s Ultimate Genesis Collection for PS3 and Xbox 360, which feature Kid Chameleon alongside a varying number of other Sega classics. It also garnered a standalone release for the Wii’s Virtual Console, where the service’s suspend feature can prove particularly useful for those not up to the task of beating the game in a single session.

Despite its depth and attention to craftmanship, Kid Chameleon didn’t quite make the impact that it should have in Sega’s library and its compilation inclusions seem possible by cult support alone. It’s highly unlikely that Sega will ever revisit the license due to its somewhat dated aesthetic, but with the Marios and the Kirbys of the world proving that 2D transformation-based platformers can still find an audience, we may not have seen the last of the Kid.

Sketches: