Published in 2009 by From Software, having been developed by Silicon Studio, Onore no Shinzuru Michi wo Yuke is in fact a massively updated PSP version of a Flash game called Cursor*10, developed in 2008 by Yoshio Ishii. For convenience we’ll refer to the update as Shadow Ninja, which isn’t really a translation of the Japanese title, but would probably make a decent localized name, if any North American or European publisher had decided to publish this outside of Japan (they haven’t). The title actually translates to something like “Go the hell the way you believe in!”, or something like that – it’s a rather impolite and direct command. With Shadow Ninja being steeped in Japanese culture, containing heavy emphasis on Ukiyo-e artwork and similarly appropriate music, its release in the west at the time was just not going to happen. Even so it is an ingenious concept backed by some beautiful aesthetics and, despite some fairly major flaws later on, is still worth looking at alongside its Flash originator. For explanations, this series of English interviews with Yoshio Ishii will be referenced. It’s well worth reading the original.

The concept of Cursor*10 (and its Flash follow up) is simple: you are given 10 cursors (lives) and need to traverse 16 floors, each connected by stairs and filled with various objects to increase points, traps to steal lives, plus switches, keys and other hotspots used to activate the next set of stairs. Think of each floor as an individual puzzle, which sometimes interacts with another floor through use of switches or a key which needs shlepping to a lock three floors up. Each cursor though only has roughly 60 seconds to do his thing, before that “session” ends and you take control of a fresh cursor. As the sessions increase up until the final 10th, all the previously used cursors will continuously replay their lives – and here lies the puzzle element, since some cursors’ sole purpose will be to stand on a switch thereby allowing those that follow to access whatever’s now unlocked. Others will need to disable traps by impaling themselves on spikes, kamikaze style. In this way it joins the small genre of temporal-themed puzzle games, alongside Echoshift and TimeSlip.

Cursor*10 was in fact inspired by an earlier Flash game by Yugo Nakamura, titled Finger Tracks. As Ishii explains, “Cursor*10 was developed in New Year holidays. When I saw FINGER TRACKS: STUDY-A by Yugo Nakamura, I felt “Oh, it’s incredible”. Definitely this was the source of my idea. In this contents, a user’s mouse operation was recorded and you can see the recorded cursor movement when you replayed. You can also see other people’s cursor movements when you replayed. The data of the cursor movements were transferred.”

According to the 0Stage interview, it seems that before working on Cursor*10, Ishii also spent three days putting together an erotic version of Nakamura’s Finger Tracks, where players clicked on the erogenous zones of a naked woman, and the mouse-clicks were secretly recorded. Afterwards, during the holidays, Ishii felt compelled to work on something else, which led to Cursor*10.

“Because it’s New Year holidays, I felt like I should release something to the public. When I started developing, the game contained a square graphic overhead view and a cursor. I drew the isometric view graphics and stairs at first. Since I first decided the game to be played by climbing a tower. It was just a game for clicking in the beginning. It was a game to play by clicking stairs very quickly. So various sort of items are placed on the way. When I placed the box that opens by clicking 100 times, I thought it must be interesting if the game was played by multi-players. Many cursors are appeared in that scene which made me imagine the game could be fun with multi-players.”

If you follow the hyperlinks to Flash-based Cursor*10 and its sequel, you’ll find that the games are indeed extremely fun. They’re also quite easy, with the emphasis being on replays and attaining a perfect score. Considering their brevity, this isn’t a problem and proves immensely enjoyable.

Shadow Ninja on PSP

Kouichi Watanabe, the man behind Shadow Ninja at Silicon Studio, explained its creation. As it turned out, they decided to update the Flash original as a direct result of 0Stage’s interview with Ishii. “From Software and I were talking about making a game together for a while, and they told me that they were looking for a game for PSP. That made me search for an idea of a game for PSP. At the same time, I read an interview with Ishii-san on 0stage’s website and learned about Cursor*10 for the first time. I already knew [Ishii’s] games, but I didn’t know about Cursor*10 at all. Then I took a look at Cursor*10 and loved it. It was simply a great game.”

Watanabe went on to explain further, “I quickly made a proposal and contacted Ishii-san and From Software. If they didn’t like my idea, I just would not develop it. Not a big deal. I was pretty confident with my idea, though, because the game concept was already brilliant as a game and also Ishii-san said in the interview that anyone can borrow the idea from Cursor*10 to make another game. I thought I just need to talk to them sincerely. [His] idea was great and also the graphics were simple and neat. It was really attractive game. I was interested in how the retail version of this game would be. You know, a Flash-based web game cannot directly be converted to a retail game. The design must differ because the players’ tastes differ. Cursor*10 is a high-quality web game, but it cannot be a retail game as it is. I had to think what kind of changes I could make.”

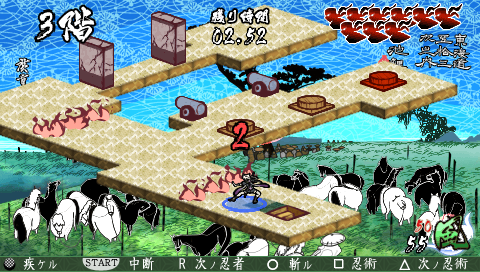

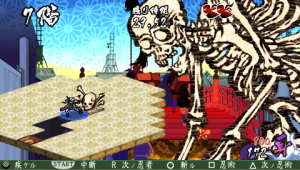

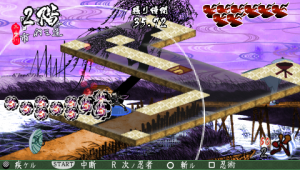

The biggest changes were aesthetic, and despite some gameplay tweaks the basic mechanics remained the same. Credit must go to the Silicon Studio team for taking such a simple concept and embellishing it to the point of being viable as a commercial release. Whereas the original Cursor*10 had an extremely minimalist, monochromatic, geometric styling – almost bordering on being styleless – Shadow Ninja is resplendent to the point of excess. As such it is gorgeous. Look at these screens and listen to the music on Youtube, and try to say it isn’t one of the most beautiful games you’ve seen.

Mechanical changes involved switching the cursors with little ninja men, plus replacing the various boxes and pyramids with enemies, bosses and other destructible scenery (grass, lanterns, etc). All of it cosmetic to suit the new Ukiyo-e styling. The major change was the addition of magic. Each floor is made of tiles, and as your ninja runs across these he absorbs them as magic power to facilitate various spells: a stone statue to sit on trigger switches; fire magic to kill enemies and light special lanterns; wind magic, also to defeat enemies and blow-out the flames on special lanterns. According to some screenshots, there appears to be water magic later on – but this is unconfirmed. In addition there are a wide range of extra features such as cannons to destroy blocks, invisible holes to drop you down a floor and all manner of bridge-based puzzle switches. Most noticeably this all gives proceedings some major physical weight, since you control a man bound by gravity as opposed to a fleeting ethereal cursor.

Coupled with the pseudo-time-travel element of multiple ninjas, a diverse variety of really awesome puzzles are available. Some involve timing your ninjas to strike a boss at precisely the same time, while other bosses are immobile and simply need as many ninjas as possible to attack willy-nilly. Some puzzles require two of them stand guard at a pair of lanterns, batting away encroaching enemy whirlwinds, while a third sets about lighting them and a fourth proceeds to attack the boss who appears. Some sections require going up stairs and dropping through holes into new areas, or sacrificing ninjas for the good of the subsequent. It’s especially exciting in stages which magic use but only have limited floor tiles to collect – those collected are cumulative and respawn with each new session, but shadows of your former self can still collect them. So it becomes a race against yourself to grab all you need. It’s a fantastic feeling to reach your final ninja and watch as each of their actions, independent of each other, come together like a massive jigsaw puzzle to interlock and complete the stage. To limit repetition there also checkpoints which activate a portal, so after clearing six or so floors, when the next session starts you can warp directly to floor seven. The range of puzzles and objects you can interact with is extremely impressive given the simplicity of the original.

If Shadow Ninja has a flaw it’s that its original concept can’t handle the increasingly complex ideas thrust upon it, leading to inevitable frustration in later stages. Watanabe spoke in interviews about needing to expand the concept for commercial release, though perhaps he went a little too far when adding layer upon layer of complexity.

One of the most infuriating stages involves an invisible maze of holes. The only way to traverse it is through trial and error, falling down each hole, running back up the stairs and trying to edge your way slowly through it, all while a 60 second timer counts down. When a session ends all the holes you’ve discovered disappear, until the mirror image of the previous ninja discovers them again. This is useless, since the maze requires several of these sessions to work out, forcing you to memorise earlier holes and you blaze on ahead, while former shadows flounder. Even with a full compliment of ninjas the stage will require restarting several times. Other annoying stages are those with a maze of bridges which needs to be built by flicking switches – none of which are obvious in corresponding to a specific bridge. Early versions of this puzzle are easy with six bridges, but later stages have considerably more, and the only way to proceed is through random trial-and-error, flicking every switch, hoping for the best, and then going round and flicking them all again until the maze is complete.

These two examples highlight the major problem with Shadow Ninja: the increasingly complex situations are not compatible with the timer. A puzzle game like Tetris, for example, also requires speedy thinking, but you can often recover from several successive mistakes. With this, the mistakes are exponentially cumulative as you move on to the next ninja. Often you’ll near the end of a stage only to realise that because your first ninja was slow in pushing some switches, all subsequent ninjas were utterly doomed as a result. You could waste a ninja trying to correct things, but this only throws everything else out of synchronisation, and you’ll find yourself trapped behind a gate because two ninjas ended up pushing the same switch, both initially to open it, but the two combined resulted in its later closure.

If the above paragraph is confusing to read, that’s because time travel is itself confusing, and dealing with umpteen independent ninjas all flicking switches, turning bridges and causing chaos, ends up being more frustrating than fun. It’s not a question of practicing either, since you can never “get good enough” to complete the later confusing stages in a single go – your only option is to play, work some of the puzzles out via trial-and-error, and then restart the level forearmed with temporal knowledge. The original Cursor*10, which it must be emphasized is a fantastic game, in contrast never suffered these problems, since its 16 floors were in effect a single stage, and the simplicity of this meant it never overstayed its welcome.

In its defense Shadow Ninja does have plenty of content should you grow tired with any one stage. There’s a length Story mode, where you’re able to accrue experience and level-up various attributes (number of ninjas, strength of magic, etc), while there’s also a substantial Mission Mode, with standalone stages where you’re already maxed out and have specific goals to achieve high-ranking scores (such using less than a specific amount of magic).

Initially fantastic, before souring somewhat under the brunt of an over-zealous puzzle-master, Onore no Shinzuru Michi wo Yuke stands as one of this generation’s forgotten Japanese gems. Accepting the fact you might grow frustrated before the end-screen, it’s still worth investigating. Or at least playing a demo of. For those concerned about the language barrier, NTSC-uk has a translation article explaining its various menus.

As a side note, it’s also totally worth visiting Yoshio Ishii’s website, NEKOGAMES and checking out his other cool flash games, including the Hoshi Saga series.

SPECIAL THANKS AND HYPERLINKS:

Fantastic and detailed interview with Yoshio Ishii

PSP trailer

Cursor*10

NEKO GAMES

Perfect run of Cursor*10

Inspiration for Cursor*10