Inspired by writer and composer Matthew Burns’ stressful experiences in the video game industry, as well as therapeutic uses of software and the gig economy, Eliza is a visual novel that ties together all of these elements in a well-written narrative, which explores the psychologies of its characters and the complexity of present-day issues with a keen eye.

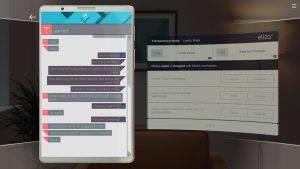

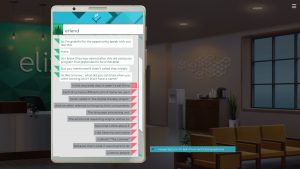

You play as Evelyn, who decides to sign on to work for Eliza, an automated counseling service that uses a homonymous AI. Her job is to read Eliza’s responses in face-to-face sessions – to serve as a “proxy”, a human avatar that allows clients to relate more to the AI and its advice. The service is a sort of Uber of therapy: clients make an appointment and proxies are assigned to them, and like Uber drivers, proxies have little agency in their job. Their ulterior task is to keep a neutral tone and be faithful to the script given by Eliza, which is displayed on a visual device that also shows a variety of biometrics.

As will become evident in your first sessions as Evelyn, it’s an unsustainable system. While clients are given a disclaimer that Eliza isn’t meant to substitute proper therapy, the seriousness of their issues and the fact that the AI won’t refer them to professional care makes it clear that people are seeking help in the wrong place. To make matters worse, Eliza’s advice boils down to prescriptions of medication – antidepressants and analgesics with Byzantine names – and software providing visual simulations of idyllic landscapes.

For a service aimed at helping people with their problems, it’s quite tone-deaf and materialistic. It suggests mindless catharsis and analgesia for disappointed, broken people who see no purpose in life and or their jobs. That is, if they have a job at all – one of Evelyn’s most memorable clients is an old lady who’s about to be thrown out of her apartment and resorts to selling marijuana to make a meager income. She’s also lonely: all she wants in Eliza is a listening ear, someone who’ll care.

In the end, you’ll prescribe her medication for her shoulder pain and that’s it – you can’t even break script, or you’ll get fired. Something clearly needs to change, and luckily it turns out that Evelyn didn’t choose to work for Eliza out of opportunity or chance. There’s some mystery at first regarding some familiarity of hers with her surroundings, but it doesn’t take long before the game spells it out: Evelyn was one of Eliza’s creators, a part of its original developing team. She quit it after the death of one of her co-workers – and best friends -, who died from overwork during one of many crunching sessions, in a push to expand Eliza from a simple auxiliary to therapy to a Uber-like means in itself.

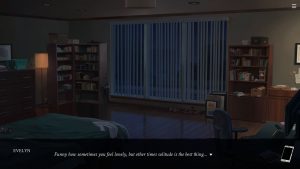

Now Evelyn returns after spending a long time recovering in exile, to get a better picture of her past and present life (which, to paraphrase her, she worked through mindlessly until it was too late). Though she initially wishes to do this investigation quietly by working as a lowly proxy, she’ll soon be discovered by acquaintances new and old, and ultimately you’ll be able to join one of these characters in an effort to improve the situation.

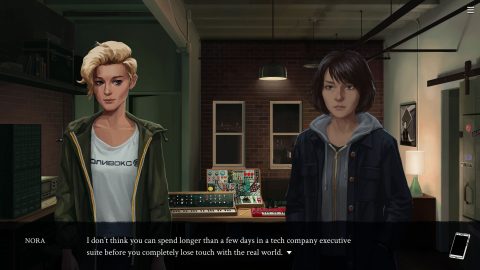

What’s nice about this final choice is that each character has their own philosophy and point of view, which are mirrored by the opportunities they offer. For instance, if you decide Eliza needs a less commercial and monopolistic alternative, you can join forces with Nora, also an old friend and a former member of the Eliza team. She firmly believes in non-corporate ways of making a living, and she invites you to develop an open-source clone of Eliza, among other independent endeavors.

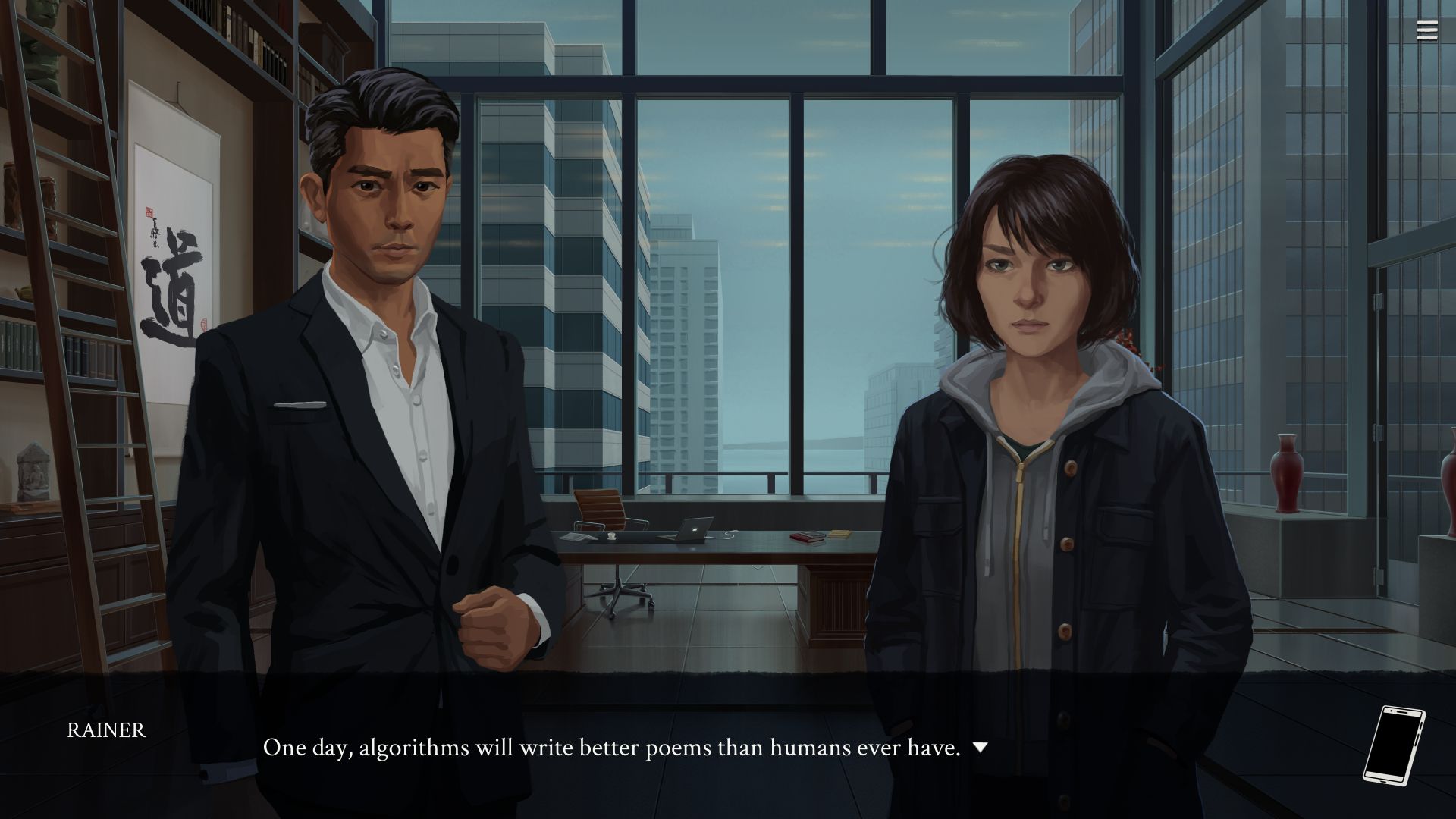

If you decide Eliza can be improved, you can join forces with Rainer, the CEO of Skandha, Eliza’s owner company. He wants to transform it into a full AI, as well as to sell it to other businesses in a movement to make Eliza indissociable from society, triggering an irreversible change similar to the Industrial and Digital Revolutions. It’s Eliza’s darkest ending, but it’s not a bad one, since Evelyn still ends up making substantial improvements to the AI’s service, making it less unhealthy. In fact, there are no good or bad endings: they all feel like different solutions to the same problem, instead.

In general, Eliza is very well-written, with characters flawed and strong in equal measure, and a story that doesn’t deliver itself to you chewed and digested. Its only flaw is that Evelyn seems to suffer from Commander Shepard syndrome, as everyone praises her programming skills and inventiveness, yet nothing in the game shows that in action. The game is also very short – in the afternoon it takes to finish it, you’ll likely be left wanting more. Especially since it discusses a lot of interesting topics that games rarely explore, such as socioeconomic alienation, the predatory nature of work culture, big data’s growing role in society, and much more.

Gameplay-wise, it’s where Eliza could use an expansion too, since it’s very linear and your choices are mostly cosmetic – excepting the multiple endings, which nonetheless are a free pick in a choose-your-destiny menu that isn’t gated by the player’s previous input. Still, Eliza’s linearity is alleviated by a variety of side-content represented by a smartphone you can access. On it, you can read emails and articles fleshing out the story’s setting, view some pixel art of relaxing Japanese city settings and play Kabufuda Solitaire – a beautiful yet brutal take on solitaire, with multiple difficulty levels reducing available free cells.

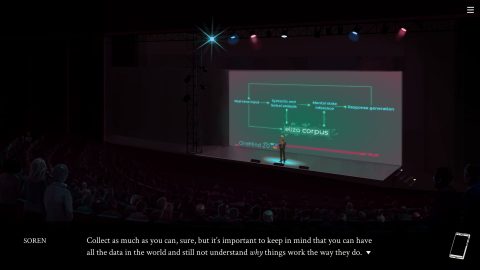

Aesthetically, Eliza is a game of clean, airbrushed visuals and somber colors. The few colorful scenes it has stand out, since for the most part the game has the aura of a slow drama or even one of Black Mirror’s less aggressive episodes. Which makes sense, since it’s set in ever-rainy Seattle and its gentrified environments – offices, convention halls, cozy cafes. Everything feels smooth and clinical, which is accentuated by Burns’ music, with electric piano-ish synths quietly making their way into the background of important scenes.

This atmosphere isn’t meant to bring the player down, however. Eliza’s thematic and causal core is suffering, exposing environments and cultures that consume those included in them. Yet, if anything, it’s a hopeful game: its gloomy aura is there to make the rare moments where you connect with the other characters more meaningful. For instance, at one point you may spend an afternoon baking cookies with a friend – while trading life stories and useful tips on how to deal with a broken family. And, near the end of the game, you can also break the wall between proxy and client, in a final act of rebellion as Evelyn grows ready to move on with her life.

Eliza’s a game of suffering, but also of change and agency. Overall, it’s a small gem, well worth a shot for those looking for a little more seriousness in their gaming. It’s developer Zachtronics’ first foray into non-puzzle territory, but like other games in their catalog, it pays special attention to the interaction between technology and humanity while maintaining a relatable narrative. It’s a warm reminder that, however alienating and oppressive our reality might be, we still have the most important thing: ourselves.