It isn’t always easy being an admirer of Yasumi Matsuno’s enticing worlds and narratives. Not only are half of them hidden behind obtuse mechanics – as is the case with Vagrant Story and at least the original version of Tactics Ogre – strictly speaking there hasn’t been a true Matsuno fantasy story since Final Fantasy XII, which is arguable, since he had to bow out in mid-development due to health reasons, and what remains is only a twisted travesty of Ivalice. It truly is a shame, for even though his style is distinctly Japanese, it’s at the same time very unique, and very atypical of Japanese RPG storytelling. Whenever he leaves one of his creations in the hands of others, only half the heart ever remains – the “true” Matsuno games are deep, dark and serious, with no plucky 18-year old “veteran” world savers or silly slapstick sequences. Well, at least he now has thrown his fans a bone with Crimson Shroud. As part of Level-5’s Guild01 project, a bundle of small-scale creations by renowned Japanese game auteurs like Goichi Suda and Yoot Saito, Matsuno’s latest work retailed only in Japan, while the West got it as a download exclusive in the 3DS eShop.

The Creator – Yasumi Matsuno

Born October 24th, 1965, Yasumi Matsuno joined Quest in 1989. There he worked on the peculiar NES action-platformer Conquest of the Crystal Palace (1990), before he created his first major work, the Ogre Battle (1993) saga. A second installment named Tactics Ogre (1995) followed, then Matsuno left for Squaresoft in 1995. With pretty much the same template as Tactics Ogre, Final Fantasy Tactics (1997) introduced the world of Ivalice, which was then to be further explored in Vagrant Story, Final Fantasy Tactics Advance (which Matsuno only produced, so that game’s abysmal writing wasn’t his fault) and Final Fantasy XII (2006), until Matsuno had to leave the development team due to health reasons. Since then he has mostly been around as a freelancer. The surprising first fruit of this career change: He wrote the story for the ludicrously violent Mad World.

Not Ivalice, but…

Although Crimson Shroud takes place in a new fantasy world, it harkens back to Vagrant Story a lot. As its spiritual predecessor, the quest takes place entirely in a single building, here the Sun-Gilt Palace of the Rahab, the monument a king of a long-lost dynasty dedicated to his queen. The game follows the Chaser Giauque and his companions on their quest into the ruins. Not quite like the Risk Breakers in Vagrant Story, Chasers are mercenaries who specialize in finding and retrieving lost, escaped or stolen persons or items. This particular contract actually involves both – an influential member of the aristocracy sent the heroes on the trails of a young monk named Andolay Cleantis, who reportedly unearthed the most forbidden manuscript of all time, the “Defense of Heresy.”

This shall require further explanation: According to legend, the world of Crimson Shroud used to be devoid of any magic until a thousand years ago mysterious artifacts, the “gifts” appeared and where soon declared God’s miracles by the Conclave of the church. Those lend their owners magical power, and soon people found ways to copy them in lower quality. The original gifts, however, were sought out and jealously kept by a secret society, the Gatherers. The “Defense of Heresy,” then, is a treatise written by the theologian Natanael, which gathered evidence for the proposition that the gifts were indeed sent by the Devil to seduce mankind. The manuscript cost its author his life, and was kept locked away by the church, until it disappeared. All that was not enough: Andolay believed that the manuscript would lead him to the Crimson Shroud, the legendary first gift.

Characters

Giauque

The man with the seemingly unspeakable name (actually it’s similar to “joke”) is the hero of the game and an experienced Chaser. Quite uncommon for a Japanese RPG hero, he is in his late twenties. He has a past of working for the Knights of the Peace as an interrogator, but ended up in his much less legitimate profession after teaming up with Lippi.

Lippi

Giauque’s partner. Formerly a bandit, he first came in contact with Giaque when he was still working for the state, and the two ended up saving each other’s lives several times. He lost his right arm and eye during a confrontation with the Knights of the Peace, but received gifts as replacements afterwards. His artificial eye reacts to scents instead of light.

Frea

Frea (according to the Japanese kana, her name is pronounced “froh”) is a Qish, member of a homeless – and godless – tribe with high magic affinity, and basically Crimson Shroud’sreplacement for elves. Giauque and Lippi saved her from being executed for heresy. Ever since she accompanied the two on their adventures, although her attitude towards Giauque can be rather gruff.

Flint

Flint commands a unit of the Knights of the Peace. He and his troops arrived late at the Palace of the Rahab, and he is seen in the chapter interlude sequences, interrogating a badly wounded Frea after the adventure. For most of the game it is kept uncertain what he is really looking for at the palace, but he has deeply rooted ties to Giauque.

Crimson Shroud is really only half RPG, and half interactive novel, told in interleaved narrative layers. At the beginning of the adventure, Giauque’s party has already found poor Andolay’s lifeless corpse, and narrowed down the whereabouts of the “Defense of Heresy” to the palace. In fact, the adventure is already over when the story first sets in, and the actual interactive scenes are all flashbacks, told by the captured Frea after things went wrong. This approach allows for a string of interesting literary techniques and twists, and they are applied masterfully. With further excursions towards the characters’ pasts or pieces of lore in between, the game strings a complex and colorful narrative in a world dominated by political intrigues and power struggles between the Gatherers, the church and the senate. As in Matsuno’s former works, this world achieves a rare degree of authenticity and credibility, even without us ever actually seeing much of it, just by the power of the words. Matsuno has been quoted stating that he hoped his game would be enjoyed by kids, but for that the subject matters seem a bit mature, and some descriptions can get quite disturbing.

The English translation is also excellent – it is provided by Alexander O. Smith, who already gave Vagrant Story its strong narrative voice in English and accompanied every Matsuno title since then, and his partner Joseph Reeder. It does feel a little more casual than its Japanese counterpart, albeit it’s faux old-fashioned casual speak. The Japanese text is better presented visually, though. Color coded lines for direct speech and names are unfortunately scrapped from the English script. The Japanese text is selectable in all versions of the game and learner-friendly, by the way, as it gives all the readings with the kanji. In either language the text is accentuated by a 3D effect that’s very pleasing to the eye. Unfortunately that’s the only positive thing to say about the 3D – the rest of the graphics are actually a little bit worse for it, with some strange jaggies popping out of the screen at edges.

Many of Matsuno’s games have dabbled a lot in meta game concepts intruding into the game world: Ogre Battle‘s tarot cards, the judges with their arbitrary laws in Final Fantasy Tactics Advance or the AI-gambits in Final Fantasy XII. Crimson Shroud goes one step further and downright pretends to be a tabletop RPG adventure: Its characters are all inanimate figurines, complete with a base to support their virtual balance, and the stages are only realized as much as they would be in a tabletop game, with nothing but empty void beyond.

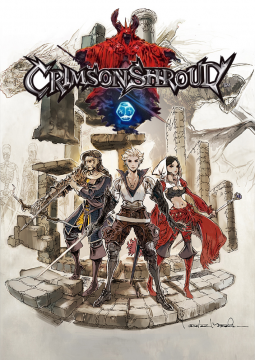

In spite of – or thanks to, rather – the near complete lack of animations or fancy special effects, Crimson Shroud manages to convey a very particular atmosphere, perfecting the deliberately artificial look that was already hinted at in Vagrant Story. Although Crimson Shroud cannot rely on Hiroshi Minagawa and Akihiko Yoshida’s talents (who accounted for the visual design of all of Matsuno’s games from Ogre Battle to Final Fantasy XII), but Squaresoft veteran Hideo Minaba (Final Fantasy VI & XII, Lost Odyssey) does a splendid job at recreating the same flair and adapting it to the miniature concept.

But the most central board game element by far is the inclusion of dice rolls in the mechanics. The game actually lets the player grab a bunch of dice (via stylus or with conventional input methods) and roll them to determine the success or failure of a number of actions. Direct attacks and buff spells work out just as in any other Japanese RPG, but the dice come into play whenever a debuff spell is used on monsters, or when characters recharge their own magic points – while the characters get their hit points recharged between battles, magic points actually decrease with each step taken on the map, so most battles begin with an upwards struggle to charge up magic power.

The game also knows a lot of variant starting situations for battles, depending on the situation in the narrative: Get ambushed by a band of goblins? Throw the dice to determine how many rounds the heroes need to react. Face enemies on a high up platform? The “battle at range” throw shows how many rounds it will take to get to get to them; until then all melee attacks get a malus. Both scenarios also exist the other way round. Quite unique is the “fog of war,” meant to simulate bad visibility. Here the accuracy for attacks is reduced, and every couple rounds each individual character gets the chance to adjust the eyes to the situation – also decided by the dice, of course.

Not all dice throws apply to combat situations, though: Sometimes players can try their luck with the dice to avoid enemies or traps. At one point, the characters even seem to literally throw dice in the story, or some other, undisclosed random method to assign a certain unpopular task.

All these actions rely on a fixed set of dice of various side numbers. In addition to that, Crimson Shroud features a very interesting combo system: Most skills and spells are assigned one of eight elements (fire, water, earth, wind, lighning, ice, light and darkness). By alternating them so that none is repeated and none is followed by the element that destroys it, the party can earn bonus dice; the longer the combo, the more faces the awarded die has. Getting to the good ones isn’t easy, though: Using only neutral skills in a character’s turn ends the combo, and enemies’ action can disturb – but also aid – it as well. Going for the highest combos severely limits the options towards the end, and forces the player to think ahead. If these requirements seems too strict, very rarely a custom die may be gained by “tilting,” when it bounces over the imagined walls of the lower screen (upon which it can be seen flying over the upper screen, past the figurines), but at the same time it is lost for the current success check. These special dice can now be added to many actions to enhance their effect. Usually the impact is straight forward, but for attacks the dice can be distributed between raising hit percentage or damage points.

There is one other purpose for the dice that doesn’t involve rolling them: After each battle, the party gets awarded loot points for its performance, which are necessary to grab any items dropped by the enemy. This can force tough decisions on the player, especially since it’s not possible to compare directly with the already owned items, but dice can be traded in for additional points, always achieving their highest number (so a d12 always gives 12 points here, for example).

Crimson Shroud has a crafting system in place to improve upon them, but it’s a far cry from the micromanagement nightmare in Vagrant Story: Items can only be improved by melding two of the same together, or by attaching a new spell from a spell book to them. There an additional item that is needed as a catalyst for the process, but the game provides it so generously that they might as well not be there. This process plays a central role in improving the party, too, as all spells are bound to items, and the game has no experience points or levels for the characters.

The characters are not entirely devoid of abilities of their own, though: Every once in a while they get to chose one new skill from a selection of three after a battle. Some of those are equivalent to spells, while others have unique effects like the aforementioned magic charge-up or a lure to increase the dice values gained from combos. Their most important property, however, is being counted separately from other actions like attacks, spells or items, allowing a second move per turn and greatly expanding the tactical possibilities.

The most common critique against combat in Japanese RPGs is the “press X to not die” syndrome that makes most of them very shallow experiences devoid of challenge. Not so in Crimson Shroud. Here every enemy encounter is a threat, at least on the first playthrough. All the mechanics described aren’t just unnecessary fluff, but become essential when facing the chapter bosses, who by their stats are about the same strength as the party. There are no “one hit wins” random battles, every encounter matters, and takes its time. It is possible to gain the upper hand through item grinding, though, as unfortunately standard encounters are repeatable indefinitely. The greatest flaw of the game probably is that one part (two for the good ending) that forces the player to repeat an encounter multiple times to get a random and rare but crucial item drop.

More than with most other video game designers, a game made with Matsuno’s full involvement is usually immediately recognizable as such – although that might in part be the result of him often working with the same core team of talented artists. While he had to do without his preferred character designers this time, the music is once again composed by his long time friend Hitoshi Sakimoto. It is a solid soundtrack with the usual epic battle themes and eerie dungeon music, with the odd beautiful melancholy melody for the more contemplative scenes. Occasionally the music also gives way for atmospheric ambient sounds, to great effect. The score is very reminiscent of the Ogre Battle and Ivalice, and just like Vagrant Story‘s soundtrack a perfect fit for that gritty dungeon crawler feeling, although not quite as memorable overall.

Alea iacta est

Crimson Shroud no doubt is a very focused experience, and that focus lies on the narration and combat. Exploring the palace means nothing more than picking locations on a map and reading the room descriptions. The party indeed gets around quite fast, and it’s not hard to see the credits roll after 6-7 hours. However, that ending is quite the downer, and a new game plus option makes it possible to explore further areas in the castle and bring the adventure to a more satisfying conclusion, albeit through a very obfuscate solution. Enemies and items are scaled accordingly the second time, but the better part of the quest remains exactly the same, including all the narration. Known text can be skipped, but going through all the screens and perspective changes can get pretty annoying. It is great to have a JRPG that isn’t grossly bloated for once and gets to the point, but ultimately the forced repetition feels like padding. One single quest with the play time of both playthroughs combined would have been a more appropriate scope. To those waiting for an 100-hour epic, Matsuno’s tribute to classic tabletop adventures won’t make for too much more than an appetizer, albeit a particularly tasty one.

The perfect fit for Crimson Shroud would have been as part of a handful of small adventures, kind of like Telltale Games releasing their games in seasons – preferably with save game transfer, in the best spirit of classic RPGs. Crimson Shroud is sufficiently long for what it sets out to be, bu the game’s interesting systems still feel somewhat underexplored at the end of the adventure. With Matsuno already having left Level-5 right after completing the project, it would be a shame if they just went to waste now. As short as it is, the game is worth much more than the few bucks it costs in the 3DS eShop, and no RPG fan should miss one of the most fresh, yet at the same time most traditional genre offerings in a long time. Even for those that are jaded towards JRPGs by now, Crimson Shroud might just be the right cure to bring back that lost magic.

Links:

Official Japanese Homepage

Official English Homepage