The life simulation genre has gained a decent following in the West (especially among casual gamers) with the hit series The Sims and its imitators. This style of gameplay with no defined victory conditions, focus on daily activities and the player giving tasks to the characters who may or may not actually go through with them can be traced back to a Commodore 64 game known as Little Computer People released in 1985 by Activision. A year later Activision would release a very different take on the life simulation genre: Alter Ego.

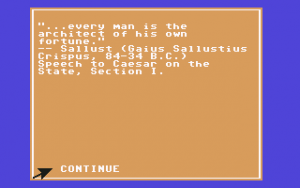

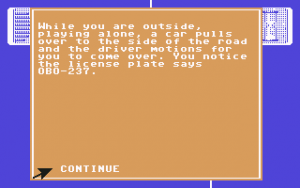

Instead of animations depicting a character waling around the house, Alter Ego went for minimal (even for a Commodore 64 game from 1986) graphics and a lot of text. Instead of daily routine, it focused on memorable events and emotional responses toward them. Where Little Computer People had players interact explicitly with the characters and The Sims made them some kind of unseen force ordering the characters to talk with each other, watch television or burn their house down, the character in Alter Ego is controlled directly in a choose-your-own-adventure fashion. In some ways, it’s more similar to modern Japanese ‘life sims’, ‘raising sims’ and ‘dating sims’, although with the scheduling/time management aspect downplayed significantly.

Alter Ego (IBM PC)

Alter Ego, while quite non-linear, does not have the sandbox aspect of Little Computer People and its followers. Instead, it attempts to create an authentic story of a single person’s life – all of it, from birth to death – by relying on the psychological knowledge of its designer: Dr. Peter J. Favaro, a therapist and court-appointed mental health service provider specialising in issues related to parenting, divorce and anger management. According to Favaro, many of the things that happen in the game are based on the interviews about important events in life he conducted with various people.

Peter J. Favaro, Ph.D.

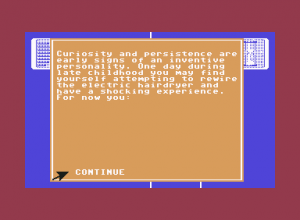

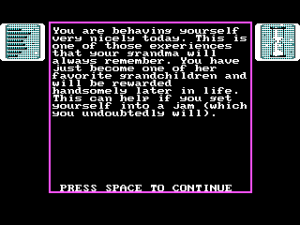

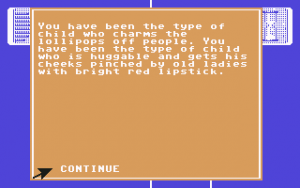

Character creation in Alter Ego is done through a simple psychological test consisting of several true/false questions regarding personality, ethics and attitudes, followed by short choose-your-own-adventure segment taking place as the character is being born. This, combined with a bit of randomization, determines the initial statistics for the character. It is also possible to tell the game to roll a completely random character.

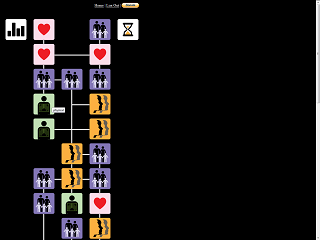

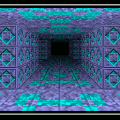

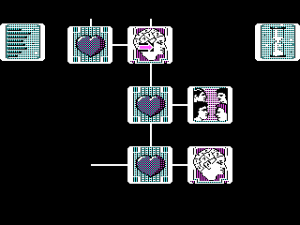

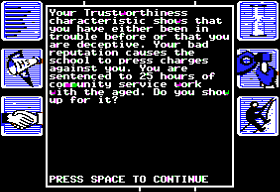

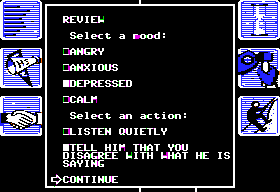

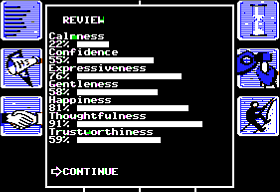

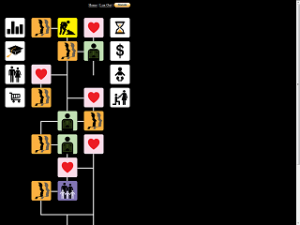

After the character is created, the player is taken to the main gameplay area: a scrollable tree graph depicting a series of connected icons. Each of the icons represents a single scripted event. These belong to different categories – e.g. ‘family’, ‘work’, ‘physical’, ‘social’ or ‘intellectual’ – and their outcome depends on the combination of player decisions (usually, the player must pick both an action for the character and their emotional reaction to the event), stats (keeping in line with the game’s psychology theme, most of them describe the character’s personality and social skills) and random chance. The event’s outcome usually affects the same stats it checks for, which makes sense but may lead to annoying situations in which having a low physical, confidence or trustworthiness stat leads to an inevitable downward slide. After an event is completed, its icon disappears from the tree so it cannot be picked again.

Alter Ego (IBM PC)

Some event icons are placed outside of the tree and don’t disappear after use. Those are the events relating to education, employment, love life and starting a family. They’re chosen randomly and while usually not very interesting, they provide the only ways of acquiring a college degree, getting married or finding a source of income. The game also features random events not chosen by the player which happen after completing a different event and more often than not have negative consequences (e.g. a family member commits suicide).

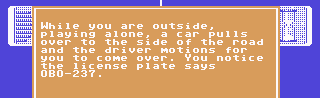

Alter Ego (Commodore 64)

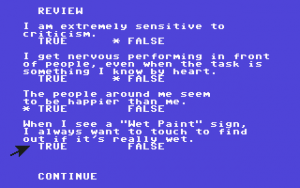

The game is divided into seven sections – each a reference to one of the seven ages of man from the ‘all the world’s a stage’ monologue from Shakespeare’s As You Like It. Each section begins with a literary or philosophical quote from the likes of Sallust, Jonathan Swift or Arthur Balfour and ends with a scorecard descriptively summarizing your stats. Finishing a section requires completing a certain number of events (which is hidden from the player). The events themselves are always (with an exception of the ‘constant’ ones which stay mostly the same as long as they’re available) appropriate given the character’s age: a physical event may be a confrontation with a bully for a child, witnessing a robbery for an adult and joining a softball team for an old person.

As the number of events that can be performed during each of the game’s sections are limited, the player is forced to choose between the more fun scripted events or the less interesting ones concerning college or dating. As in real life, this means balancing priorities between responsibilities and the desire to experience something new.

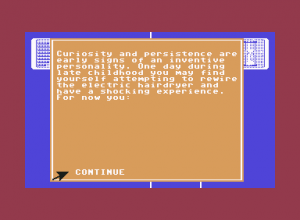

The events are usually well-written and feel like things that can happen to real people (or at least real people from the American suburbs who lived during the 1980s, as the game’s narrative scope is limited to what its designer knew). The game always stays fairly realistic, never going too crazy or over-the-top. While in practice it means that most of the characters will be pretty average people, the game actually gives the player some options to do unusual things – ranging from helping a depressed woman find a reason to live to becoming a popular musician (or, if you want to see the darker side of ‘unusual things’ – dealing drugs or getting murdered by a serial killer). Unfortunately, while the game’s stat-based gameplay usually deals well with the continuity of mundane events (e.g. arguing with your parents all the time may lead to them not helping you when you need it because a stat determining your family relationships fell too low), it’s not enough to mask the lack of event chains when something less mundane happens – getting arrested means that your trustworthiness stat will drop but nobody’s ever going to mention that it happened.

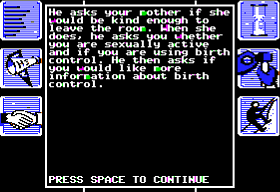

As has been alluded to several times, Alter Ego wasn’t afraid to address some pretty heavy themes like suicide, depression, crime and addiction. While the game never gets too explicit with its descriptions of sexuality and violence, the back of the game’s box nevertheless includes a warning about such content. Additionally, the player is always allowed to skip sex-related events. In general, Alter Ego handles some of the more serious themes pretty well, although there are some preachy bits: a serial killer event is basically a choose-your-own-adventure version of a stranger danger PSA while the decision to have unprotected sex results in the narrator giving you a lecture about the importance of contraception.

Alter Ego (Commodore 64)

Interestingly, despite the obvious 1980s setting, the game rarely feels dated. Sure, some of the slang used by teenagers sounds silly now and so does the idea of spending thousands of dollars on a computer just because it has a hard drive. Those are the exceptions though as most of the situations you encounter in game deal with issues which, while not always universal, are still relevant today. Also, the focus on personal life means that if the game will be remembered in the future, people may still find it relatable.

Alter Ego (Commodore 64)

Versions of Alter Ego for different 8- and 16-bit computers play the same (although the interface of the Commodore 64 is the easiest to use as the player can move the cursor freely, while Apple II and IBM PC versions restrict movement to following the lines on a tree graph) and share the lack of music (every version has different sound effects although they’re extremely minimal anyway). The C64 version has probably the best graphics as the icons are reasonably clear (despite being monochrome) and the blue background with borders changing color depending on your age is easier on the eyes than the squashed icons on black background in Apple II and DOS versions.

Alter Ego (Apple II)

The real differences between the games are in the male and female versions available for each platform. While most events are shared between them, there is a noticeable number of gender-specific ones, especially those dealing with sexuality (e.g. a boy’s first erection and a girl’s first period). If the character’s gender itself is not a concern, the female version is slightly preferable as it was released later and as such fixes some of the bugs and typos present in the original release.

Alter Ego (Apple II)

A company known as Choose Multiple LLC (which seems to have produced no other games) recreated the original game in JavaScript and made it playable for free through web browsers (although there is a nag screen after every section urging you to donate money through PayPal). This version combines male and female Alter Ego (you select a gender during character creation), features high-resolution icons and is probably the easiest way to play the game on a modern system. On the flipside, its random number generator introduces a few annoying bugs (there is a very high chance of being stood up at the altar, conceiving a baby seems impossible, playing softball is basically suicide etc.). The mobile versions are adapted from the web game and share its strengths and weaknesses, although they seem a bit pointless as the web version is free and most phones nowadays have no problem running it.

Alter Ego (Apple II)

Some of the issues regarding the game (e.g. the way some of the more unsual events are handled or it US-centrism) have been acknowledged by the developers of the mobile and online versions who’ve compiled a wishlist consisting of features they haven’t added to the game yet. Unfortunately, it doesn’t seem like they’re actually trying to add them – the web version wasn’t updated since 2009 and the updates to mobile versions mostly consist of bug fixes. It’s a shame though – the game would be pretty impressive if it could portray homosexuality, career in politics, terminal disease, life outside of America or technological changes without losing the quality of writing or psychological authenticity.

In the end, all versions are similar enough, so the choice of platform is just a matter of personal preference. Alter Ego is an interesting game regardless, and it’s worth playing to experience a completely realistic – mundane even – setting in video games done right. Despite some tacked-on educational events, the game’s writing is strong enough to elicit an emotional response (of different kinds – the game can be both funny and sad at times) and the psychological insight prevents it from feeling fake.

Web version screenshots

LINKS:

Konstantin Dimopoulos’ interview with Peter Favaro

Scans of Alter Ego manual (C64 version)

Technical information about the DOS version (bugs, scripting, version differences)

Alter Ego on C64 Wiki

Cover scans from Mobygames