Games about sumo aren’t exactly common, and when they do get made, they’re typically one-on-one fighting games that attempt to simulate the sport. As early as 1991 in Japan (1993 in North America), the developer Kindle Imagine Develop (KID) decided to take sumo in an entirely different direction with Sumo Fighter: Toukaidou Basho (Sumo Fighter in North America) by creating a platformer starring a sumo wrestler rather than a fighting game.

The story of Sumo Fighter is as typical as they come: as Bontaro Heiseiyama, your job is to rescue Bontaro’s lover, Kayo, from ninjas who have kidnapped her and taken her to a castle in Kyoto. The journey takes you across the Tōkaidō, one of the “Five Routes” of Japan’s Edo period, starting from Edo and ending in Kyoto. While there’s no way to tell where exactly you are during each step of the journey, the game uses a horizontal map to show your progress, much like Capcom’s Ghosts ‘n Goblins.

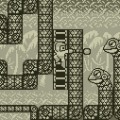

At a glance, Sumo Fighter looks and plays much like other platformers on the Game Boy. You move from left to right, avoiding pits and defeating enemies until you make it to the end of the stage. The main thing that makes Sumo Fighter stand out are its light RPG elements that affect the way you approach the game. Bontaro has two attacks – a slap that turns into a finishing throw after enough hits and a stomp attack that hurts all grounded enemies on-screen but is slow and can be interrupted. By collecting experience points, the player can upgrade the power of these moves as well as Bontaro’s health, allowing him to take up to eight hits. Once enough experience is earned to level up, the player gets to choose which stat is increased, providing a welcome bit of choice in the way they build up Bontaro. This system would also set the foundation for KID’s 1992 cult classic KickMaster, which uses the same idea of implementing RPG elements into a quirky platformer.

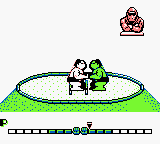

Experience can be acquired via items of varying value found in stages, but the most effective method is to find hidden minigames throughout the stages. When you find the corresponding icon (a Torii, a kind of Japanese gate) and are shown a set of three cards to pick, there are three different minigames you can reveal (along with a chance of getting nothing!) – thumb wrestling, arm wrestling, and paper wrestling. All three minigames are played in the exact same way, requiring the player to press A as a moving gauge goes back and forth in order to have it land as close to the center as possible until the player or the computer is victorious. These minigames get much longer and faster as the game goes on and you only get a single chance each time, so it can be stressful having Bontaro’s growth so reliant on them.

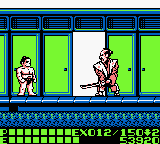

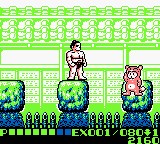

Most of the game’s enemies fit in with the Japanese setting of the game and there’s a fun variety of them to encounter. While you’ve got the obvious ninjas, samurais, and birds, you’ll also encounter some real oddities along the way, such as tiny sumo wrestlers, small men who magically grow into larger and more detailed men, and yōkai such as the Kasa-obake (a living umbrella) and the Rokurokubi (a woman who can stretch her neck like a giraffe). There aren’t any notable platforming challenges to speak of, with most levels being a straight line, so never knowing what bizarre foe you’ll encounter next serves as welcome motivation to keep playing.

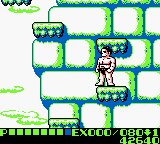

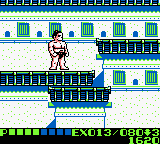

While the general flavor of the game is consistently charming, it does falter mechanically. Bontaro’s sprite is huge, so the platforming never feels quite right, especially with the Game Boy’s small screen making it difficult to avoid damage from surprise enemies or large spikes placed liberally throughout stages. Bontaro also has zero ways of attacking enemies above or below him while in the air, making some enemy arrangements particularly devious. Bosses serve as the biggest frustration in the game, with most of them taking far too many hits and being just as big as Bontaro themselves. The bosses also lack the creativity of the regular enemies, as they’re all large fighters with one or two attacks. The standout bosses include a guy who looks like he came from Fist of the North Star, a fight on top of a castle with an opponent who exclusively uses kicks, and a ninja who burrows underground, then jumps up and shoots what appear to be eyeballs at the player.

The game has two difficulties by default, easy and hard, with a third difficulty called “Super” that is unlocked by beating hard. The harder difficulties don’t simply increase enemy health or damage, but instead mix in new enemies, change enemy placement, and even alter the rules of the game. On hard or super difficulty, losing all of your lives and continuing brings Bontaro back to level zero in all stats, which does not happen on easy mode. Some examples of altered enemy placement on higher difficulties include stage 1-2, where a new floating head enemy that drops a power-reducing skull item is placed throughout, and stage 4-3, which litters the sky with birds that can interrupt your jumps. The selected difficulty also affects the ending text, with beating the game on super being the only way to actually see the credits. Sumo Fighter has passwords that preserve the selected difficulty and stat levels, so you thankfully won’t need to unlock super mode each time you play.

Thanks to the large sprites used throughout, Sumo Fighter looks very nice compared to other Game Boy platformers. All of the characters encountered throughout have detailed expressions and animations that exude personality. Bontaro’s sprite in particular is impressive, with detail dedicated to showing off his bulging muscles as well as some minor animation flourishes, such as the way Bontaro takes a second to return to a neutral position after a slap attack. There’s a nice variety in backgrounds as well, and the multiple vistas you’ll see help establish the scale of Bontaro’s journey. While they don’t play into the actual level design, you’ll see sights like bridges, oceans littered with boats, mountains, decadent castles, and bamboo forests in the stages you traverse.

The soundtrack for the game is composed by Nobuyuki Shioda, one of KID’s primary composers who worked on games like KickMaster, Low G Man, and Summer Carnival ’92: Recca. While the music lacks the bombast and memorability of KID’s NES titles, it’s a respectable effort overall. All of the tracks use sounds that are befitting of the Japanese setting, and the game cycles through tracks every few stages to avoid being too repetitive. The music in most stages tends to be upbeat, but sometimes changes to a more dramatic tone in stages such as 2-2, which helps capture a sense of adventure. The music used for the boss fights is also fittingly intense and panic-inducing with its intentionally discordant sound.

Nowadays, Sumo Fighter is only remembered for being among the most valuable of Game Boy titles, but it’s an interesting platformer that was ahead of its time in some ways. The way it incorporates light RPG elements into a different genre is something the industry as a whole would begin to adopt much later down the line. It was also the first sumo-themed game to break free from the restrictions of a 2D fighting game during a time where non-arcade efforts were typically limited in nature. It’s not as polished or exciting as the Game Boy’s finest platformers like Super Mario Land 2: 6 Golden Coins or Castlevania II: Belmont’s Revenge, but it’s still worth acknowledging for its originality on a console inundated with platformers.