The Japanese strategy RPG scene in the middle of the 2000s was dominated by Nippon Ichi. With Disgaea: Hour of Darkness blowing up when it went stateside in 2004, the PlayStation 2 was quickly saturated with the company’s cutesy anime visuals, lighthearted storytelling, and quirky gameplay as compared to the genre’s otherwise serious, nation-spanning conflict approach that reflected its tabletop war game origins.

Pinegrow’s Stella Deus: The Gate of Eternity did not follow that shift. The game’s narrative, centered on warfare, religious strife, and a world beset by climate disaster, follows much more closely in the archetypal SRPG tradition of Tactics Ogre and Final Fantasy Tactics. It even features a Hitoshi Sakimoto soundtrack!

The origins of Stella Deus can be traced back to the much-maligned 2001 PlayStation game Hoshigami: Ruining Blue Earth.

On its surface, Hoshigami looks and feels like the kind of game any fan of the genre loves, but it was justly panned for its clunky gameplay – ending a turn requires going through SIX different menu options – and absurd difficulty spikes that demand hours upon hours of tedious grinding to progress. It also features permanent character deaths (without even the three-turn grace period present in FFT), replacements for whom have to be recruited back at level 1, requiring yet more grinding. The best walkthrough for the game on GameFAQs recommends going through at least a dozen levels of the game’s training dungeon before even starting the main quest.

This failure behind them, the core team behind Hoshigami left MaxFive, the studio behind its development (the game was also its sole release) and formed Pinegrow, where they developed Stella Deus.

It’s a clear spiritual successor to Hoshigami. As noted in Bitmap Books’ A Guide to Japanese Roleplaying Games, both the names “Hoshigami” and “Stella Deus” translate to “Star God.” The second game can be seen as an attempt to rectify the mistakes of the first. It is mostly successful in that goal, if not without its share of baggage. Unfortunately it didn’t receive the financial and critical breakout success of its contemporary Disgaea, making it more of an echo of a bygone age than a continuation of the old SRPG ways.

Stella Deus is a gorgeous game with a rich world, a solid battle system, and a promising storyline, but it drags along at a snail’s pace, offers little by way of character customization, and altogether doesn’t vary the way it engages with the player enough to justify the nearly 50+ hour commitment it requires to complete.

That said, it blows Hoshigami out of the water, and it’s a shame the team never developed another successor.

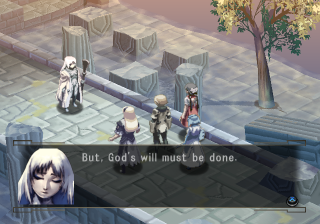

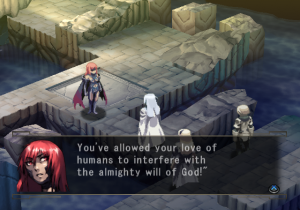

Stella Deus takes place on a continent called Solum, which is rapidly being engulfed in a deadly mist called the Miasma. A religious sect forms in response to the Miasma’s spread: The Aeque. This group teaches the doctrine of “a peaceful end,” encouraging people not to see the Miasma as a disaster but as God’s will. “Those who accept this and await their fate will be welcomed at His side,” the Aeque say. Basically, abject acceptance of humanity’s destruction wrapped up in a nice woo-woo mystical shroud.

The spread of this gospel is successful and allows the people of Solum to find hope within their despair. At the same time though, it makes them complacent. So much so that an ambitious warmonger named Dignus takes advantage of this weakness to step forward, gather an army called the Imperial Legion, and conquer the one remaining major kingdom on Solum: Fortuna.

The game centers on a young man named Spero who works with his friends as spirit hunters, which are warriors who kill and absorb the life energy of Spirits – translucent creatures that exist throughout the continent. The spirit energy is used to power alchemical inventions that Spero’s friend and mentor Viser, who works under Dignus, is sure will save the world. But Spero diverges from Viser when he meets a girl named Linea, a descendant of the lost kingdom of Anima, who convinces him that killing Spirits is, in fact, accelerating the Miasma’s spread. Spero then betrays Viser to help Linea reach the Gate of Eternity, a door into the spirit world thought to be only a myth. But if it exists, it could bring new Spirits into Solum and push the Miasma back, saving the world from a destruction that most already see as inevitable.

Characters:

Descriptions taken from the game manual.

Protagonists

Spero

Age: 16

Weapon: Dual Katana

“A kind and optimistic young man. He continues to train with the sword techniques he learned from his late father.”

Linea

Age: 18

Weapon: Bow

“The last remaining descendant of the Anima kingdom’s Royal lineage. She understands her position and asserts herself easily. As all Anima, she believes humanity can live in harmony with the spirits, and she seeks to mediate between the two.”

Grey

Age: 17

Weapon: Spear

“Good friends with Adara and Spero, despite his sarcastic barbs. Grey’s cockiness tends to get him into trouble. He’s overly sensitive when it comes to Adara, though.”

Adara

Age: 17

Weapon: Argyrion (Magic coins, basically)

“A cheerful and intelligent girl who is good friends with Spero and Grey. She’s self conscious about her arm, which is an artificial limb created by alchemy.”

Gallant

Age: 33

Weapon: Axe

“A strong warrior who walks softly and carries a large axe. He lives in harmony with nature, and can communicate with spirits, though not as well as Linea.”

Prier

Age: 11

Weapon: Staff

“Lumena’s loyal attendant.”

Lumena

Age: Unknown

Weapon: Staff

“The high priestess of the Aeque, she believes God’s will for humanity is a peaceful end. She

is very motherly, and has a romantic relationship with Avis. Lumena is currently a prisoner of the Legion.”

Avis

Age: 22

Weapon: Sword

“The former prince of Fortuna. After the Imperial Legion destroyed his kingdom, Avis’s hatred for Dignus prompted him to take up arms and lead the Resistance.”

Viser

Age: 24

Weapon: Alchemic Sword

“A brilliant alchemist who hopes to create a world free of the Miasma. He continues his research, despite alchemy being forbidden.”

Tia

Age: Unknown

Weapon: Gloves

“A strange girl who’s stalking Spero and the party.”

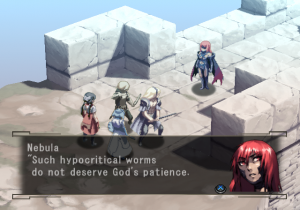

Antagonists

Dignus

Age: 44

Weapon: Broad Sword

“An Overlord of war and destruction, he slaughters anyone affected by the shadow of apathy. If destruction is the will of God, he intends to destroy God himself.”

Echidna

Age: 29

Weapon: Katana

“One of the four generals of the Imperial Legion. She is a skilled swordswoman. She has fought with Dignus in the past and lost, but she was permitted into his army. She is constantly in search for strong opponents.”

Croire

Age: 32

Weapon: Bow

“One of the four generals of the Imperial Legion. He is Dignus’s attendant, and attempts to use his power for his lord.”

Viper

Age: 34

Weapon: Axe

“One of the four generals of the Imperial Legion. He is cruel, sinister, dirty and mean. He is the epitome of evil. He is in charge of the ruffians of the Legion, massacring anyone they want.”

The scenario was supervised by fantasy writer Ryo Mizuno, who created Record of Lodoss War. In its bones, there’s a strong story to be told here. Like Final Fantasy VII, the plot is one of those nice standard JRPG “the magical fossil fuel we’re using is unsustainable and we’re destroying the planet” riffs, with a misguided religious sect thrown in for good measure. But there’s not much to it. The characters don’t change much beyond “I used to not agree with you, but now I agree with you.” There’s barely any plot progression after the promising setup – you just go from place to place looking for the Gate of Eternity and fighting members of the Imperial Legion along the way. Nothing about the Gate of Eternity or the Imperial Legion ever really changes either. Villains who show up in the beginning, like Echidna, barely even make another appearance until the final act. Viser – the emotional tie between the heroes and the villains – completely disappears for large swaths of the game. Altogether the story holds no surprises, with no late game reveals to complicate the narrative. Barely anything happens to shake up what is established within the opening few hours.

That said, it is nice how thematically coherent Stella Deus is. It has a simple, treacly message of preserving hope and showing love for humanity, but to its credit it sticks to that message consistently throughout the game. And such themes are definitely worth considering now when climate despair, misanthropy, and indifference are on the rise in the real world.

One nice touch to the writing is how this forward-thinking outlook clashes with what is revealed to be Dignus’ true motivation for seizing control of Solum: An unadulterated lust for violence and power. That’s not unusual for a JRPG antagonist, but the reasons for Dignus’ ambition are fleshed out more than usual. Dignus’ cruelty is the point. His thinking brings to mind the Judge from Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian and the haunting “War is God” philosophy that forms the backbone of that novel.

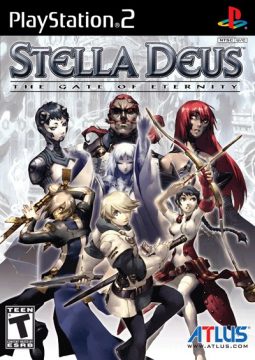

At a glance, the main draw to Stella Deus is probably its graphics. This was the first art director/character designer credit for Shigenori Soejima, who later did the character designs for Persona 3 and onward. He was also mentored by Kazuma Kaneko, who has been involved in MegaTen art design as far back as Shin Megami Tensei II.

The character designs are very distinctive, using hand-drawn brushwork portraits (Soejima would later opt for a cel-shaded style instead in the Persona series). The idea was to steer clear of standard fantasy aesthetics like heavy suits of armor and go for outfits that look fresh and unique while still making sense within the decaying, desertified setting of Solum.

As Soejima explained in an interview, Stella Deus was his first opportunity to helm the character art direction in a game, and he wasn’t sure if he’d refined his own style yet.

“At first I was at a loss, but I eventually decided that the best way to go would be for me to start by figuring out what I thought was the best visual balance,” he explained. “By going back to the artistic style from my days of drawing just for the fun of it, I finally settled into the style you see today. So my memories of Stella Deus have more to do with my drawing style dilemma than the actual process of character design.”

Being green to directing a videogame’s art does not diminish Soejima’s attention to detail, though. He goes on in the same interview to explain how the developers worked on characters in tandem with the setting, ironing out world building specifics as nitty-gritty as whether the swords are forged or cast. This resulted in a visual style to the characters, their outfits, and their weapons that’s consistent with the setting they inhabit.

This, unfortunately, just makes the sexual elements of the character designs feel all the more out-of-place.

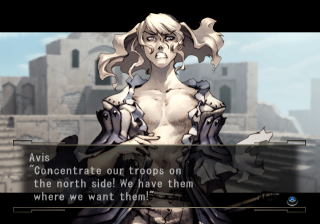

You will undoubtedly notice the character art’s sexualized aspects. Lumena is the most obvious case, decked out as she is in a form-fitting angelic dominatrix outfit. To be fair men get to reveal their bodies too, like the sultry-eyed, open-shirted Avis. This artwork is detailed, for sure, and well-drawn, but its efficacy is hit or miss depending on how you feel about overly sexualized characters. If not in the artwork, certainly there’s egregious breast bouncing pixel animation for a lot of the female characters in battle, Linea in particular.

It seems strange that this erotic aesthetic doesn’t have any bearing on the plot, which is not in the least sexual, when so much attention to detail went into other aspects of the character art. If one wanted to make the argument that the eroticism is the point, it would have been good to at least include some weird psychosexual drama a la Aeon Flux. Like, for what reason exactly do the ceremonial vestments for the high priestess of a doom cult include erect metallic nipples?

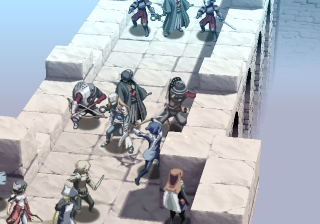

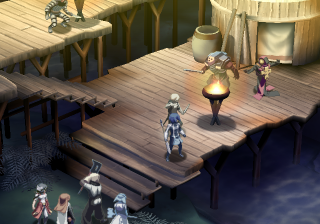

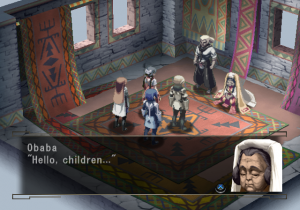

Visually, the game takes place on the battlefield, on the linear bullet-pointed world map, and in menus. Most of the actual graphics you see are in dialogue scenes – which use well-drawn but forgettable blurry backdrops behind character portraits – or in battle

Battles are viewed from an isometric perspective, which can be shifted around with the right analog stick. The backgrounds are by necessity blocky and abstract, but they work well. As little of it as you get to see, these glimpses still manage to impart a solid sense of what Solum looks like. The textures of the 3D environments were influenced by Hayao Miyazaki anime, none more obvious than Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. It’s hard to not get at least a little bit enchanted by that approach. But some maps can be bland – there’s a lot of gray and brown going on.

The most outstanding visual aspect on the battlefield is the detailed character models. They’re taller and more evenly proportioned than those seen in Stella Deus‘s PS1 counterparts – they were developed in high resolution and animate beautifully.

Occasionally – usually at the end of a chapter – there will be a CGI cutscene made by Japanese studio Kamikaze Douga. The studio did the opening and ending cutscenes for Breath of Fire: Dragon Quarter and the opening animation for JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure. Its work in Stella Deus is unfortunately pretty ugly. An attempt was made at cel-shading, but it looks flat and awkward compared to the captivating character portraits seen through the rest of the game. Only Linea and Spero are ever featured in these scenes, too, even when it would make sense for other characters to make an appearance as well.

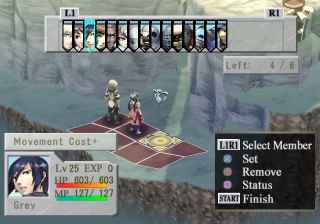

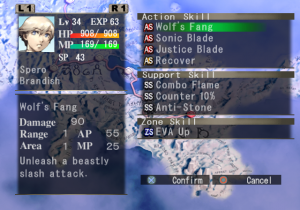

The crux of the battle system lies in the action point system, a feature carried over from Hoshigami. Basically, you have seven characters on your team, and each character has a 100 point AP gauge. Every action costs AP. Moving, attacking, casting spells, using items – everything diminishes this gauge. A character can act multiple times per turn as long as they still have AP. Spero, for example, can attack three times from a standstill. Your healer can probably move a couple squares to reach a far away ally before casting a spell. Most magic can only be used once, with exceptions like low AP-cost status curing magic.

The hitch is that the more AP you use, the longer it takes between turns. This makes for some really fun strategizing, using just the right amount of AP so you line your character turns up in a row for maximum impact.

The AP system has its quirks though – if you have a character who you don’t want to do anything with yet, you have to do some frivolous action like move back and forth or else their next turn will keep coming up too fast because their AP bar is still full. But in general, it’s a delightful way to mix up the SRPG experience. It’s implemented far better than the comparable RAP system in Hoshigami, where it tries to go for more customization – at the end of each turn you can choose how much AP you want to expend, thus deciding when you want that character’s next turn to come up – but it ends up being more cumbersome than anything.

There are terrain effects and elevations to consider, but there are also character field effects. Both you and your enemies can equip certain status effects, both positive and negative, that impact anyone standing in nearby squares. One can restore the MP of your allies, for example, while another can cause the dreaded “fear” status effect in those around you, which can cause a battle to come to a complete standstill since fear prevents a character from attacking or using skills. Most bosses have a debilitating field effect that you need to prepare for ahead of time or hope you can get around. This is a welcome challenge, but it can be a drag because you often don’t get to that enemy until late in a battle and might not know what to prepare for until it’s too late.

Boss fights are another interesting aspect of the gameplay because they have an almost puzzle-like approach to getting around their field effects. A further challenge comes from how most bosses automatically surrender after you’ve depleted a certain amount of their health. That seems like a blessing, but you can get secret characters if you “overkill” them instead. Since most bosses’ surrender marks are over 1,500 HP, it’s difficult to kill them in one go but rewarding if you manage it.

The main way of going about getting them to zero is to use team attacks, where you attack in unison with other nearby allies. There are four generic team attacks that you gain slowly as the plot progresses, and other, stronger attacks that you have to discover as you play along. Spero, Adara, and Gray, for example, have a special attack together. Most combinations are between characters who have a strong relationship as you’d expect, but others like the one between Gallant and Tia can surprise you.

There are four “secret” characters who you can recruit after accomplishing a certain number of invisible criteria and completing sidequests. Even the most popular walkthroughs for the game online can’t seem to agree on what those criteria and sidequests are. Getting these characters almost doesn’t even matter because the two strongest aren’t recruitable until the very end of the game, three and two battles before the last.

As entertaining as it can be, it’s a shame the battle system gets tedious after a while. Especially during the unnecessarily drawn-out sequence about three-quarters of the way through the game when you have to go to four elemental temples to fight one regular battle and then a boss battle one after the next with little to no plot development in between.

This also isn’t helped by the fact that the further you go along, what at first appears as a healthy array of character customization options reveals itself to be fairly limited.

Equipment is just a matter of finding the next strongest item and putting on accessories that make up for each character’s weaknesses. “Ranking up” at first looks like it could be a class system, but it turns out to be merely a linear progression for each character that activates after you receive items at plot-determined points. Ranking up changes your title, gives you a stat boost, and opens up more skills, but you can only ever rank up in one direction. The skill system is fine – you gain skill points as you do experience and use them to gain active skills like magic, passive skills like a 10% experience bonus, and field skills like the ones described earlier – but each character has a limited selection and a limited amount of slots to equip them in.

Characters can also learn skills through scrolls, which you mostly obtain by fusion. The fusion system is promising, but it’s too arcane to function beyond randomly smashing together items and hoping for the best. It’s worth playing with because you can get good skills and equipment before they’re available for sale, but it’s hard to be strategic about it. The fusion sidequests are ridiculously involved – often requiring dozens of fusions to get the right items – making it a wonder how anyone was supposed to figure them out without a guide.

Balancing is leagues ahead of where it was in Hoshigami. Ally unit deaths are no longer permanent and only cause a slight stat penalty, which is insignificant enough not to make a difference if that character doesn’t die often. Stats can be increased using SP anyway. But the balance is still not perfect. The game still requires some grinding, which you can accomplish in the training dungeon, the Catacomb of Trials. But if you’re even slightly underleveled battles can be near impossible and if you’re slightly overleveled they can be a complete joke.

The game’s music was written by Hitoshi Sakimoto and Masaharu Iwata under their company Basiscape. Its theme songs and vocals were performed by Japanese singer Reiko Ariga. It’s all fantastic, if not as iconic as some of Basiscape’s other work. Most tracks are less than two minutes long but don’t feel like it. For example, even though it’s only a minute and a half long, the game’s main battle theme – which you will be hearing a lot – is very listenable, with a maelstrom-like effect similar in style to Philip Glass.

The less said about the English voice acting the better. Its only saving grace is that it can be turned off in the options.

Stella Deus received decent reviews at the time it was originally released, mostly floating somewhere in the 6 to 7 out of 10 range. Not bad, but such scores show the game did not make enough of an impact with players to get out of the shadow of the Nippon Ichi craze of the mid-2000s.

Many members of the team behind Stella Deus were absorbed into Atlus. Their names can be seen in the credits of newer MegaTen games. Stella Deus was, for example, directed by Akiyasu Yamamoto, who now mostly serves as project manager on MegaTen games, especially the Persona series. The closest comparison to Stella Deus among Atlus’ output since it was released is the Devil Survivor games, which are good in their own right but aren’t epic war dramas like Stella Deus and its antecedents.

Other core team members disappeared from the gaming industry entirely, the most regrettable perhaps being chief programmer Yoshinobu Narimasu, one of the main brains behind the battle system, whose only videogame credits are for Hoshigami and Stella Deus.

Atlus quietly re-released Stella Deus as a PlayStation 2 classic on the PlayStation Network for $9.99 in 2013, two years shy of its ten year anniversary. It will likely be the last time anything new about the game develops.

You can’t help wonder what a follow-up would have looked like if the team had been given the chance to make one. Consider how there wouldn’t have been any Souls games if it weren’t for wonky, polarizing experiments like the King’s Field games (not to mention Shadow Tower, Evergrace, and Eternal Ring) to provide a foundation. Something that built off what Hoshigami and Stella Deus got rolling could have really made an impact. But as it stands, these games sadly only made a small and largely insignificant contribution to SRPG history.