Nintendo first introduced the “action hero” style of Metroid when they released Metroid Fusion for the GBA in 2002—eight years after Super Metroid. Nearly a decade on, Fusion dialed back the exploration elements, and streamlined the structure and expanded Samus’s moveset instead. In Fusion, Samus could jump while in Morph Ball form, grab onto ledges and pull herself up, wall jump with greater ease, and was a much quicker, more athletic, and better animated version of the character. These mechanics were later expanded upon in Metroid: Zero Mission, a remake of the very first Metroid, for the Game Boy Advance, making that one of the best controlling Metroid games to date.

Metroid: Other M is what you get when Nintendo decides it wants to make a game that’s as fast-paced and stylish and streamlined as Metroid Fusion and Zero Mission, and does it at the cost of almost everything else. It’s also the first and only time the company has made something that could be accurately described as “a murder mystery in space”.

On the very surface, Metroid: Other M plays largely like Fusion. The game is played holding the Wii Remote sideways (no option for a Classic Controller), and you run through areas of enemies, pulverizing them with your laser before they get too close. The game takes on a derelict space station called the Bottle Ship, where Samus runs into members of the Galactic Federation platoon but operates independently most of the time. You explore this space station, linked with a central elevator that takes you to three sectors with different biomes, themed on plant, fire, and ice. Each room or corridor is part of a large, interconnected map, and your ultimate goal is to explore the entire structure, collecting powerful weapons and upgrades along the way until you’re virtually unstoppable. Typical Metroid stuff.

That’s where the similarities end. For starters, Metroid: Other M is a 3D game, but unlike the Prime games, it’s displayed from the third person perspective (most of the time). Every part of the world is modeled in 3D—even linear spaces like corridors—which allows Samus to move in three dimensions. Combat and dodging are at the core of Other M, often requiring Samus to get up close and personal with the enemy, rather than taking them out from afar. When you enter a room in Metroid: Other M, enemies don’t stand around waiting for you to shoot at them from a safe distance. Instead, they hurl themselves at you, sometimes two or three at a time, and you need to be able to dodge out of the way by tapping a direction on the D-Pad at the last second. Follow a dodge up with an expertly-timed press of the 1 button and Samus instantly charges her beam to full power, which you can let rip in the enemy’s direction.

This is where Other M feels fun on a very fundamental level. Normally, Samus’s charged shot takes a second to charge up. You can do it whenever you like, but it takes a second, which means you don’t want to be stationary while doing it. If you try to do it right after a dodge, though, it charges up instantly, giving you incentive to learn the dodge-and-charge timing. You can run around and shoot at enemies, keeping them at bay, while waiting for them to strike, then counterattack. Every part of the game is carefully choreographed with a variety of enemy types mixed together, each with their own attack patterns and nuances, and learning how to effectively deal with them without taking too much damage is half the fun. Some enemies may divebomb you from the air. Others curl up into a ball and roll themselves at you. Others dance around, firing lasers and occasionally jumping in for a strong melee attack.

Most enemies also tend to have a bit more health than you’d expect, which is why Samus now has melee takedown attacks.

As you tussle with enemies, they’ll gradually enter a weakened state where they’re prone to melee attacks. Either their wings will get clipped off and they’ll be grounded, or they’ll slow down, or you’ll be able to momentarily immobilize them. When it happens, Samus will be able use a takedown move, either to weaken them further or finish them off entirely. This is usually done by getting in close, holding down the 1 button, and moving Samus in the direction of the enemy.

The action Samus performs depends on the enemy type. In the case of the annoying flying wasps that you’ve de-winged, she grabs them by the tail, spins them around, and hurls them into a wall. Some enemy types (like the Space Pirates) even have multiple takedowns you can perform on them, depending on whether you move in on foot, or jump at them after they’re weakened. These melee actions can also be used to interrupt enemy attacks, and they give Samus a real sense of athleticism and strength. They flow in and out of the rest of Samus’ moveset—sort of like special moves in a fighting game. Since enemies in Other M have a tendency to bully you, melee interrupts and takedowns are an effective means of ending the fight quicker, and doing it stylishly. It’s also a way to present cinematic action similar to Quicktime events, but without the distracting button inputs flashing on screen or tedious button mashing that tend to typify them.

It’s nothing if not stylish. There’s a slickness running through every part of Other M, from its combat encounters to the cutscenes to the way Samus moves. Unlike Super Metroid or Metroid Prime, Metroid: Other M’s Samus is designed like a sports car, with bright, reflective colors and a sense of sleekness and athleticism in every movement. This is a Samus that puts her whole body into whatever she’s doing, and the animation conveys body language in a way that very few games manage even today. One of the greatest joys of Other M is simply watching Samus dash from one end of a corridor to another, her feet creating just the right amount of impact against the floor to help convey a sense of weight and agility all at once. One of the game’s bosses can even be defeated using the Shinespark. It isn’t required to beat him, but learning the timing to pull it off feels great, especially once you’re good enough to consistently replicate it during repeat playthroughs.

(There are other little stylistic flourishes that add up, too. A nice detail is how Samus’ visor reacts to her emotional state. It powers down and turns transparent during quiet, conversational moments, and lights up to obscure her face when she’s getting ready for action.)

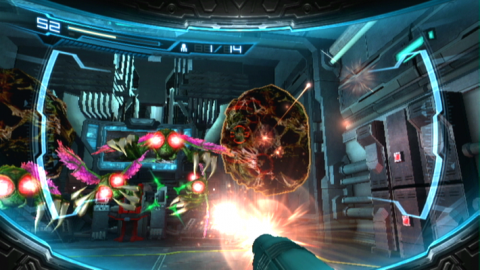

Finally, there’s the more unusual aspect of the combat: first-person aiming. At any point, no matter where you are, you can point the Wii Remote at the television, and Samus enters a first-person aiming mode, which can be used to fire missiles. If you stop pointing and go back to holding the remote sideways, the action goes back into third-person. There are no buttons involved—you’re literally required to perform a physical action in real life to aim, and enemies are designed to interrupt you. This makes for an intense back-and-forth with enemies, as you try to find opportune moments to go into first-person and let off a couple of missiles, while they do everything they can to knock you out of it. Boss encounters in particular require heavy use of this ability, which often makes them frantic, stylish, reflex-intensive affairs. This is also important because you can only use missiles in first-person mode. It does require a fair bit of controlling juggling, and the Wii sensor isn’t always the best at keeping up with switching between the two modes, so this aspect isn’t quite as well integrated as the rest of the combat. It also feels like it’s an unusual compromise between the “classic” third-person Metroid games and the (then) modern first-person Prime games.

The game’s camera serves to present Samus and her antics in the best possible light, too. Because Metroid: Other M is played using a Wii Remote held sideways, there’s no way for the player to control the camera—nor is there a need to do so. Other M’s camera constantly highlights the action from all sorts of dynamic angles to keep things interesting. In one room, you might control the action from a side-scrolling perspective. In another, it might change to a third-person view behind Samus’s back. In yet another, you might see things play out from an overhead/isometric viewpoint. Fascinatingly, none of this feels abrupt or disorienting in the slightest. Every single part of the game’s world is constructed in a way that the camera sweeps or pans or zooms out to the appropriate viewpoint in an elegant, unintrusive fashion. Since the camera is constantly switching between so many different viewpoints, you need to figure out how to let the character aim. Other M handles this rather elegantly, by having Samus auto-aim at enemies that are closest to her or directly in her line of sight. This frees the player up to focus more on movement and dodging instead. The downside to the game’s controls is that you’re playing a 3D game using a digital directional-pad, rather than an analog stick, though it’s something you can get accustomed to.

By the end of the game, you’ll have settled into that familiar Metroid dance, dashing and jumping and navigating back-and-forth between areas, and Other M’s excellent camerawork will make your entire playthrough look like a well-choreographed demo. If you’ve ever wondered what a “cinematic” game from Nintendo would look like, this is it. Other M is a fantastic lesson in how to create a cinematic game that still feels gamey.

There are a few oddities as the result of the focus on action. Primarily, enemies no longer drop health or weapon restoratives. Missiles can be recharged at any time by holding the Wii remote vertically and holding the attack button, which leaves you defenseless for a moment. Health recharging works similarly, except you can only do it right when your energy is in the critical range. This takes a few more seconds, so it’s critical to find a safe moment to do it…and they aren’t always available. Otherwise, the only way to replenish your health is through save station terminals. The weapon power-ups are the same as found in other games, though new is the Accel Charge, which increases the speed at which your charge shot powers up. A difference of a few milliseconds may not sound like much on paper, but it makes all the difference in the heat of battle.

One of the more irritating aspects of the game are sections where you need to go into first-person mode to hunt for a specific item in the scenery. There’s nothing to do here but rotate around until you’ve locked onto whatever it is the game wants you to find before you proceed. These are usually quickly solved, and while it feels like the designers wanted more opportunities to put you in Samus’ visor, they just feel like meaningless wastes of time.

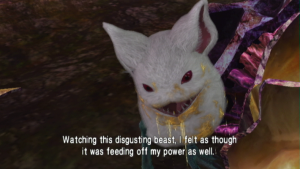

Other M is sometimes referred to as “Metroid Gaiden” because it was made by Ninja Gaiden developer Team Ninja. That title is fitting for other reasons, too. The word gaiden means “side story” in Japanese, and that’s what Metroid: Other M is—a regular day in Samus’ bounty-hunting career before things quickly go awry. Other M is a much more low-key adventure than you’re used to. There are no Space Pirates invading, no military-authorized mission to exterminate a planetful of Metroids, and no interplanetary travel. Instead, there’s Samus and a bunch of her ex-military buddies, all locked up together on a spaceship housing illegal experiments, and getting picked off one by one as they try to get to the bottom of things.

Other M is no Agatha Christie novel, but has some of the makings of a decent thriller. There’s foreshadowing aplenty, a couple of fun plot twists that fall neatly into place when they’re presented, certain closures that are left to the imagination in a very Twin Peaks-esque fashion, and excellent camera work during the game’s in-engine cutscenes, which make it feel a little bit like an indie horror film.

The game’s whodunnit yarn is also woven into an examination of Samus’ character, and this is one of the most lambasted elements of Other M. The game’s character study largely focuses on the way Samus has grown and matured over the years, with an emphasis on her strained relationship with Adam Malkovich, her former commanding officer and mentor who was referenced in Metroid Fusion. It’s the first in the series to feature fully voice-acted cutscenes, and while a lot of the cast does a good job, the actress voicing Samus sounds extremely somber throughout the entire affair. (Her drone-like reading of the line “the baby”, in reference to the Baby Metroid from the previous games, has been routinely mocked.)

Other M’s opening cutscene gives the player an extended look at Samus without her Power Suit on, emphasizing both her femininity and the fact that she’s in an emotionally vulnerable state following the events of Super Metroid. A short while later, a distress signal unexpectedly reunites her with Adam and her old military unit, and the encounter stirs up even more emotions that she’d prefer remain suppressed. Over the next several hours, the game fiddles with a bunch of interesting ideas that action games rarely concern themselves with—depression, insecurity, the difference between strength and wisdom. There are moments where it all feels true to life, and others where the soliloquies can feel heavy-handed. It’s also odd because, outside of the internal monologues of Metroid Fusion, Samus has never had much of a personality, so it feels strange having these feelings mapped onto a character that was mostly a blank slate. It’s even more bizarre given that the game takes place between Super Metroid and Metroid Fusion—the themes it explores make sense for a rookie, not for a combat hardened veteran. Plus, Other M’s unskippable cutscenes also mean that you have to sit through the exposition the first time you play the game (although, they are skippable on replays).

And then, there are the moments where Video Game Story Logic torpedoes any sort of believability entirely. Like nearly every other game in the series, Metroid: Other M has you start out with just a small subset of Samus’ abilities. The justification for this in Other M is that because Samus is working with her old military unit again, her commanding officer needs to authorize use of her more advanced weapons and techniques, as they pose a very real danger to other human beings. This is all well and good, until Samus eventually runs into a volcanic area overflowing with lava, but isn’t authorized to turn on her Power Suit’s heat resistance until you’re well into the sector and at a real risk of dying from the high temperatures. The game clearly wants your first lap of this area to feel a little more threatening and dramatic than usual, but justifies it with a story decision that makes no logical sense, even within the context of that universe. It’s ludonarrative dissonance at its worst.

At the time of Metroid: Other M’s release, scenes like these gave rise to the notion that maybe Samus was being a little too subservient to her old commanding officer, and sparked a larger debate around father complexes, sexism, and the depiction of women in video games. But the central point of Metroid: Other M is that someone can be both strong and vulnerable, both confident and insecure, and most importantly, have trouble with authority but still understand the importance of being a team player. While the game doesn’t explore these ideas all that well, it does have a lot of heart and manages to weave them into an interesting tale of intrigue, illegal experimentation, and a handful of entertaining sci-fi tropes.

Think of it like this: when producer Yoshio Sakamoto made games like Metroid back in the 1980s, they were drastically limited by technology, but over twenty years later, he was freed with these constraints. However, during those intervening years, Metroid ended up inspiring an entire subgenre – it’s one-half of the “Metroidvania” moniker – creating a mismatch between the expectations of the original designer and his audience. While Sakimoto wanted cinematic action, Metroid fans wanted to explore maze-like caverns and space stations. Sakimoto also wanted to explore Samus’ character, but fans greatly preferred the silent version and letting their heads fill in the gaps. It’s clear this was the direction Sakamoto was taking the franchise after Fusion, so it’s not like Other M emerged out of nowhere.

The story is a major reason why Other M is so contentious, but it’s only part of the issue. For starters, it’s very linear in terms of progression—it’s very much the follow-up to Metroid Fusion in that there’s not much actual exploration, as the route to your goal is pretty well mapped, you just need to poke around the scenery a bit to get there. There’s back-tracking, just like there is in every Metroid, but like Metroid Fusion the story dictates when you’re allowed to venture back to older areas.

Then there’s the music. If you go into Metroid: Other M expecting the melodious synths of prior games, you’re going to be disappointed. Most of the game’s soundtrack is ambient and its presence is barely felt, with only a few tracks really standing out.

Finally, there’s the art direction. Other M is no Metroid Prime. Following up Metroid Prime 3 was always going to be a tall order, but Other M doesn’t even try. On a character animation level, it looks fantastic and feels incredibly smooth, but lacks a lot of the environmental beauty of the Metroid Prime games, which had been the only 3D Metroids up until that point and had set expectations very high as far as art and design sensibilities go. Granted, Retro Studios and Team Ninja excel at different things, but Other M does attempt a lot of neat gameplay tricks with its setting and 3D environments, and would have benefitted from a richer, more vibrant color palette.

It’s definitely not an ugly game, though. Other M lets you go into first-person mode wherever you are, which means that each area had to be designed to look good upon close scrutiny. It’s quite the technical feat.

Metroid games tend to receive widespread critical acclaim, while Other M‘s reception was a bit more mixed. It has a fairly poor reputation among the fanbase, particularly since it was the last “true” game in the series after the widely lauded Prime games. For the next decade afterward, there were only two middling 3D spinoffs for portable consoles, and a decent remake of Metroid II for the 3DS. It’s hard not to get the impression that Other M did real harm to the series, but Nintendo may not feel that to be true. Other M’s depiction of Samus has been proudly featured as the face of Metroid in every Super Smash Bros. game since, and a lot of its gameplay ideas have been expanded upon in Metroid: Samus Returns. Given that these mechanics were well received, they’re likely to continue being a part of Metroid going forward.

Given just how different Metroid: Other M is from prior games, it is understandably hard to forgive the expectation gap – but while a cinematic action game may not have been what Metroid fans wanted, it still pulls off that action part spectacularly well. And in spite of its mechanical differences, it still looks and feels authentically Metroid. This, along with its eccentric control scheme and the way it combines action-platforming with the backdrop of a thriller, it’s the kind of game you don’t see every day. Or even every decade. And that’s so very Metroid.