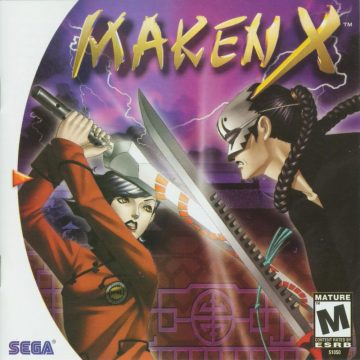

Maken X is an anomaly of a video game. Of Atlus’ two Dreamcast projects (the other being the horror game deSpiria), Maken X is both their first game on the system and the one they invested the most of their energy into. The ties to Atlus’ previous work on the Shin Megami Tensei series are apparent, and major figures like artist Kazuma Kaneko, writer Katsura Hashino, and musician Shoji Meguro were assigned to work on the game. Yet it’s difficult to tell what Atlus’ goals were for this game. Their plans were reasonably big – the game was reported on as early as 1999 and it showed up at trade shows like TGS – but there’s not much to glean beyond that.

Looking at the end result only further confuses one’s understanding. The game’s influences are various (American action movies, Apocalypticism, cyberpunk) and they manifest through several styles of play (arcade, beat-em-up, roleplaying game), but they never form into a coherent whole. Instead, they exist parallel to each other, each one promising some of that coherence but ultimately lacking the understanding it would need to make that happen. Many of the successes Maken X arrives at are accidental rather than by design.

Most people’s first instinct when discussing this game is to situate it alongside first person shooters. The causes for this are numerous: the game’s first person perspective and action-oriented gameplay; the contemporary growth of the first person shooter genre (Unreal, Half-Life, Goldeneye, Deus Ex, etc.); discussions from the time of the game’s release approaching Maken from this angle; and marketing material framed Maken like this with language like, “Imagine a combination of a 3D fighter and a first-person shooter, and you’ll get the idea.” But on closer inspection, the comparison is incredibly misleading. Japan’s interest in first person shooters has always been sparse, and Japan’s history with first person perspective games has its roots elsewhere: in dungeon crawlers and adventure games. Neither genre intersects that much with Maken X’s design.

The same applies to Atlus’ own fighting game/first person shooter comparison. There’s the pedantically obvious difference between this game and first person shooters: it doesn’t focus on shooting or resource acquisition as much as it does using a predefined set of attacks to slash and/or bludgeon enemies. But the differences go deeper than this. First person shooters, as the early vanguards of video game realism, sought above all else to create seamless worlds the player could explore and inhabit. Any other decision a game made had to be in service of that. Comat, for example, was designed not only to prevent lengthy interruptions to that exploration, but also to motivate it further with keys to find, hidden resources, alternate paths through the level, etc.

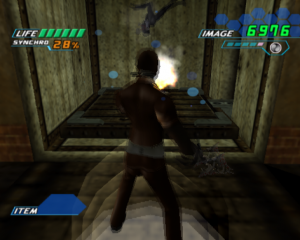

Maken X, by contrast, expresses more interest in exploring the systems it’s crafted than it does in creating a perfect illusion of reality. Despite the superficial similarities with first person shooters, the game’s encounter-to-encounter pacing centers combat above all else, and the environments are ready to follow suit. Between the tight hallways that make combat with an enemy inevitable and the open arenas force you into combat by closing off the exits until every enemy is eliminated, the world fades out of attention as you focus more on navigating the game’s combat systems – dodging, blocking, maintaining a combo, jumping behind a target to land a critical hit on them. If anything, Maken X’s fixation on rough physical encounters is more evocative of beat-em-ups than it is of any other video game genre.

But like the connection to first person shooters, it’s hard to judge to what extent, if any, this connection is intentional. The only part of this game that’s clearly deliberate is the story, which finds its roots in pop Japanese media generally and the Shin Megami Tensei approach to narrative crafting specifically. In the near future, Europe has been brought to its knees by a mysterious plague and the rise of Neo-Nazism. Whispers abound about World War III breaking out between the US and China.

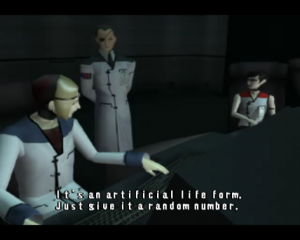

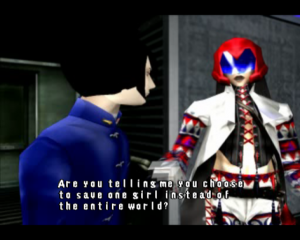

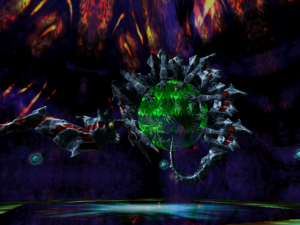

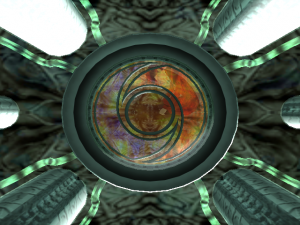

Meanwhile, a Japanese research institute is using psi power to create an artificial god: the demon sword and sentient lifeform Maken. As a medical institute with no real connections to the previously described events, their purposes in creating Maken aren’t entirely clear. However, after attackers kidnap Chief Sagami (head of the project to create Maken), his daughter, Kay, decides to wield the demon sword for herself to save her father. The plot that follows sees Kay trying to find her place in the world while deciding what to do with her newfound power to decide the fate of the entire world. The latter manifests as a Shin Megami Tensei-esque series of choices between two ideologically motivated groups fighting for control of the world. (Choosing neither is also an option.) On one side of the conflict are the Blademasters, a secret order of warriors who have dedicated themselves to protecting mankind. On the other side are the Hakke, a group that worships the psi-god Geist and seeks to alleviate mankind’s suffering by bringing about humanity’s final destruction.

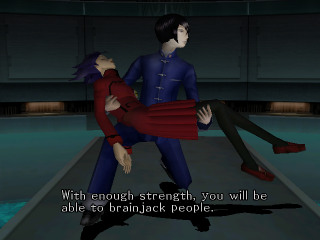

Before describing the game’s characters, it’s worth mentioning that one of the game’s major features is Maken’s ability to possess (“brainjack”) other people. Because of the sheer number of characters this brings into the story, only protagonists, antagonists, or major playable characters will be listed below. This article will also use the English names in Maken X for consistency. The Japanese version of Maken Shao use a completely different set of names for the characters.

Characters

Kay Sagami

Daughter of Chief Hiro Sagami (head researcher at the Maken Institute) and the game’s protagonist. At the beginning, she’s an ordinary high school student who hopes to work at the Maken Institute one day, but soon decides to let Maken use her psi to rescue her father. It’s for this reason that her relationship with Maken is friendly.

Although it’s Maken’s actions that drive the plot forward, it’s Kay’s character that grounds the narrative. Not only does her character arc lend the story its emotional stakes (namely through the degradation of her personal identity), but Kay herself lends a feeling of normality and relatability that Maken X otherwise wouldn’t have.

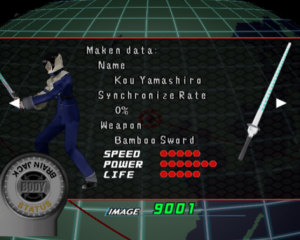

Kou Yamashiro

Kay Sagami’s friend, Kou is concerned about her well being and thus adamantly opposed to Maken’s fusion with Kay. He spends most of the game either searching for a way to reverse the Maken/Kay fusion or urging Maken to let go of Kay’s psi and return her to normal.

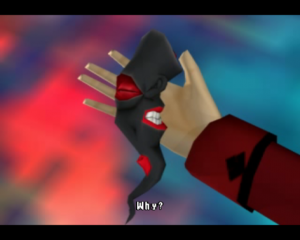

Maken

An artificial lifeform developed by the Maken Institute. It can possess (“brainjack”) other humans and gain control of their bodies; a major feature in Maken X. Although it requires another lifeform’s psi to awaken, Maken has a will of its own and will gladly do whatever it wants, regardless of what others want of it. Throughout the game, there are heavy implications that you, the player, are playing the role of Maken.

Blademaster Fei Shan Lee

A novice Blademaster and one of the earliest you can control, Fei wishes to put an end to Hakke Shaja’s plans to manipulate the masses through TV and create a lifeless world. Because she uses fans as weapons, her fighting style emphasizes quick strikes and combos but doesn’t offer her much reach, making her very vulnerable if her attacks don’t connect. She’s also the sister to Lee Fai Chao, a minor character who dies very early in the story summoning Maken.

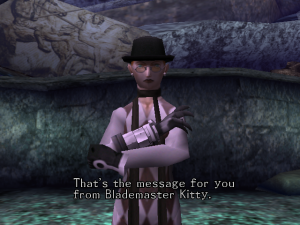

Blademaster Kitty

Not much is known about Blademaster Kitty, mostly because the game never elaborates on her character. She’s the closest the Blademasters have to a leader: she’s the one Maken interacts with the most, and in those interactions, she gives Maken directions on which Blademasters to contact. Other than that, there’s not much to say about her. From a play perspective, Kitty focuses on offense and quick strikes with flame-based attacks.

Blademaster Alys

A minor Blademaster living in Athens, Alys is the one who gives Maken the mission to defeat the Hakke around Europe. Although she has control of the wind and can attack from a distance, she’s one of the weaker Blademasters in the game.

Blademaster Tyrus

A Blademaster living in Lyon, Tyrus is portrayed as a serious character who believes in the Blademasters’ cause. (The sophisticated and lordly voice his voice actor gives him helps a lot in that regard.) As a Blademaster, Tyrus specializes in piercing enemies with heavy thrusts, making him feel heavy to control.

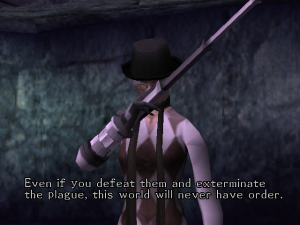

Blademaster Devon

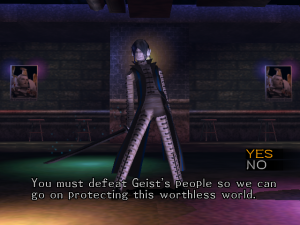

A Blademaster in Amsterdam, and presumably the owner of Club Aeolus (the club where you first encounter him). In contrast to Tyrus and the other Blademasters, Devon is very cynical. Seeing their failures to bring peace, he writes off humanity as not worth the effort of saving. In contrast to Tyrus, Devon is the swift-but-fragile type, slashing at enemies up close but dying in just a few hits.

Hakke Shaja

The Hake in charge of watching the Taj Mahal, Shaja may be the first real Hakke you encounter as a boss. After his wife’s death and his son’s betrayal, Shaja came to the conclusion that humans, being the source of all good and evil, populate the world with evil. Thus he joins Geist to end this state of affairs. He attacks with six blades (four of them attached to drone flying around his body), which, in practice, makes him a more powerful version of Fei.

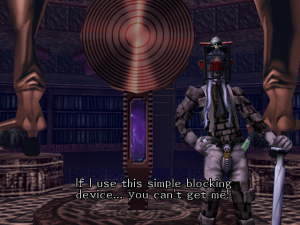

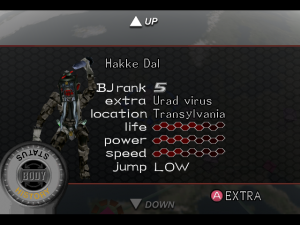

Hakke Dal

The Hakke responsible for the Grey Plague affecting Europe. He unleashed the virus in an attempt to wipe out humanity, having grown tired of all their senseless conflict. When battling him, he can either control time or turn invisible (the game doesn’t make clear which). When playing as Dal, however, neither of these abilities are available. Instead, he attacks with vials filled with his own viruses.

Hakke Margaret

A Hakke residing in Austria and ex-girlfriend to Blademaster Devon. Margaret’s defining character trait is her role as leader of a Neo-Nazi resurgence in Europe. In fact, her Nazi ideology serves as her motivation for joining Geist and becoming a Hakke. (The American version obscures this somewhat by replacing all the swastikas in the game with the Japanese character 無 (“mu”, meaning “nothingness”.) As a playable character, Margaret moves quickly but gets her attacks out slowly.

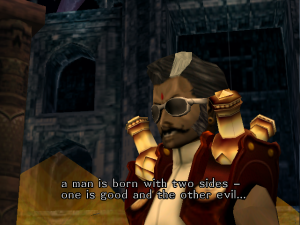

Hakke Don Regalia

A mafia Don residing in Sicily, Don Regalia is one of the hammier Hakkes in the game. He believes humans are too wicked and sinful to be redeemed in this life, so he plans to kill off humanity so he can redeem their immortal souls through Geist. In fights, he plays very similarly to Hakke Dal, attacking with explosive puppets instead of vials.

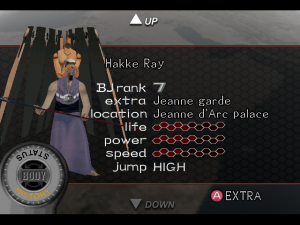

Hakke Ray

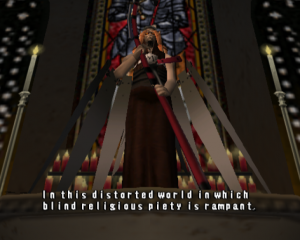

Hakke Ray is similar to Don Regalia in the sense that they’re both unintentionally humorous and they preach salvation through death, but Ray is the more religious of the two. His speech to Maken repeatedly stresses “blind faith” as a source of power, and he’s almost certainly the Pope in the Japanese version of the game, given that his level is the Vatican. (The English release occludes this detail.) When playing as him, not a lot stands out about him other than his strengths at avoiding combat.

It’s worth noting that Hakke Ray’s character design bears a strong resemblance to Persona 3’s Thanatos, even if it’s just a coincidence (the two games have different character designers). He also has the character 空 (“sora”, meaning “sky”) written on his belt; maybe to signify the emptiness he reads into the world?

Hakke Yussef

There’s not much to say about Hakke Yussef other than that he owns an oil field in Saudi Arabia. Nothing about his character stands out all that much; you only control him for a short time before better characters present themselves; and by the time you can play as him, you have no reason to engage in combat unless the game absolutely forces you to.

Hakke Brown

The president of the United States, Hakke Brown acts as a typical action movie parody of American presidents. He tries to come across as the wholesome everyman you can relate to, but is all the more off-putting because of it. In terms of play style, he’s essentially a more powerful version of Blademaster Tyrus, attacking with quick jabs and heavy thrusts.

Geist

The leader of the Hakke and a sort of psi-god like Maken. Geist believes that humanity cannot be saved from their problems without divine help, which he plans to offer them as he sees fit. Unlike the other characters listed so far, Geist is not playable in any way.

As accidental as the connection to first person shooters is, it’s easy to see how Maken, brainjacking, and the first person perspective might fit together from a thematic perspective. One of the most consistent thing about first person games is their players’ tendency to identify with the perspective they see the action from. In other words, players assume that because the action takes place from a first person perspective, that they, the player, are there in the game world driving the action forward.

It’s a position that many games have encouraged in one way or another: John Romero has gone on record as saying that Doomguy is a blank slate because he wants the player to fill in the gaps, and first person dungeon crawlers like the Wizardry series allow players to name the protagonists after themselves. Of course these games were part of a much larger trend of writing characters that would allow players to immerse themselves in game worlds (silent protagonists like Link being the obvious example), so they were by no means unique. Still, because the camera in first person games obscures the character you play as, the perception stuck more vigorously than it did for other genres/perspectives.

Maken X refuses this interpretation of first person, or at least complicates one’s understanding of it. Putting aside features like brainjacking, the intricacies of combat, or even the branching narrative, one of the game’s most notable aspects is how loosely defined its system are. Rather than explicitly state its systems and all their intricacies like, say, a fighting game might, Maken prefers to give players the mere fact of something’s existing without elaborating on anything beyond that. Movement is oddly smooth and uninhibited by terrain; jumping over enemies feels weightless; and each character’s attacks feel too quick, like they lack any sort of physical impact. The result of all this is an unreal ambiance to the game; an uncomfortable experience to play through, like you have to resist the game and fight against the perspective you’re given to get anything done.

In terms of creating a satisfying play experience, these decisions might appear confusing. But for a game that interrogates personal identity through disembodiment, those decisions make a lot more sense. Inhabiting a body with capabilities far beyond one’s own is no longer an empowering idea, but a continual source of discomfort. The character’s arms (and in one case, their monstrous torso) penetrate into your awareness, reminding you that you’ve taken control of another person’s body and thus resisting your efforts to control it. Furthermore, once you consider that the two characters you’re most encouraged to identify with – Kay and Maken – fade into the characters you take control over, find your own presence in the world disappear as you’re left with no body of your own. Kay certainly experiences this over the course of her character arc, which explores the tension between her finding her place in the world psychologically but losing it physically as she leaps into other bodies and becomes one with Maken.

Yet while these pieces connect nicely, problems arise when trying to figure out how the rest of the game is supposed to fit together. Some of it is a matter of execution. Plot points are poorly explained, like how the Maken Institute thinks that a sentient demi-god with a will of its own will function as a medical device. Related to that is the poor delivery of the narrative, whether through amateurish voice acting or the mysterious discrepancy between the subtitles and the spoken word. And while several of the game’s moments make an effort to present themselves in a goofy, over the top pulp manner (one of the enemies’ attacks is a distinct homage to Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure, of all things), just as many are funny for the wrong reasons, and it can be difficult to tell where the line between them is supposed to be drawn.

Even supposing these problems were somehow addressed, they point to much larger conceptual problems with the game regarding clarity. The narrative is most affected by this. Where similar works either present themselves as a response to some specific social development (Shin Megami Tensei, Persona, Evangelion) or eschew that altogether in favor of something more abstract and philosophical (most of Tetsuya Takahashi’s work on Xenogears, etc), Maken doesn’t neatly fit either category, mostly because it can’t decide on either one.

The result is the game denying players the wider context it discusses its ideas in but not being able to justify that denial. The virus ravaging Europe is reduced to a distant concept removed from the story’s action, as are things like the conflict between the US and China or (to a lesser extent) Europe’s descent into political turmoil. Lacking anything to ground their soliloquizing in, the conclusions the Blademasters and Hakke draw from those speeches feel trite and melodramatic; arrived at on the flimsiest of pretenses. Likewise, the conflict between the two groups feels just as contrived and one-sided. Kay’s characterization falls victim to this, too, given that she spends much of the game weighing moral conundrums based on what the Blademasters and Hakke show her of the world.

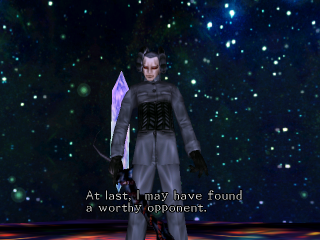

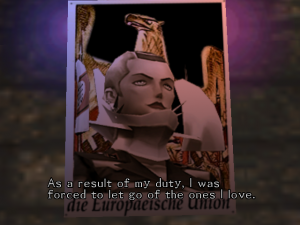

It does have a cool sense of style, though, as expected of something from the Shin Megami Tensei team. This is the first time that Kazuma Kaneko’s distinctive art style was translated into 3D, which wasn’t followed up until Shin Megami Tensei: Nocturne on the PlayStation 2 a few years later. It runs at a smooth 60 FPS, too. The music is less satisfying, though, being mostly characterless techno and electronica.

Despite all the attention given to it at the time of its release (several positive reviews from major publications), Maken X remains a sort of unknown entry in the Atlus catalog. Potential explanations are various. Maybe higher profile releases throughout the year, like Shenmue, Jet Set Radio, Final Fantasy IX, and Majora’s Mask, dominated discussions so heavily that smaller games like this were quickly forgotten. Maybe so many other games vaguely like it and with much more clearly realized identities were released at the time that Maken couldn’t hope to compete. Or maybe Atlus’ other ventures proved so financially and creatively lucrative that they never saw much reason in returning to Maken’s world. Whatever the case, Atlus has only ever revisited Maken twice: first with a manga adaptation by Q Hayashida, and then with a third person adaptation for the PS2 a couple years after the initial release.

Maken Shao: Demon Sword (魔剣爻) – Playstation 2 (June 07, 2001)

Judging by Maken X’s history, you wouldn’t think Atlus planned much with the PS2 remake Maken Shao. (The title is an unusual pun: it replaces the “X” with a “爻”, which looks like a “XX” and is pronounced “shao” in Cantonese. The symbol means a line in a trigram found in Taoist cosmology, connecting it to the yin yang power-ups symbols found throughout the game.) It was published in Europe by Midas Interactive, a publisher known for bringing over Japanese budget games like The Sniper 2, and Maken X’s middling sales in Japan further support the idea that Shao was intended as a budget project. (The game was never released in America, and unfortunately the game does not support a 60hz option for play on non-PAL televisions.) Although looking at the game itself may not completely overturn that image, it does push back against it a little bit. The game is a strong departure from its source material: cleaner cinematics rather than the still pictures of the original, a new soundtrack, and a completely revamped way of playing the game. The odd thing about this is that for all the drastic changes it makes, the problems Shao ends up dealing with are all inverse to those that plagued Maken X.

Judging by all the changes Shao makes to X’s template, it’s safe to say the former’s highest priority is presenting itself as a streamlined action game. This isn’t to say that X didn’t have similar ambitions; the marketing and press releases for it suggest Atlus was pursuing this same goal the first time around. But it was one of several goals on their minds, and their efforts to pursue all of them at once resulted in tension in the game’s design. Consider the first person perspective, and the severe limitations it placed on how much X could pursue close quarters combat. Bodily/environmental awareness was minimal and handling multiple enemies at once was incredibly difficult. In addition, pulling the camera in so close to the protagonist made the environments feel claustrophobic; hence X’s uncomfortable play style.

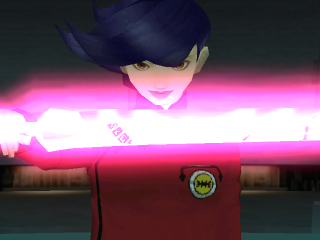

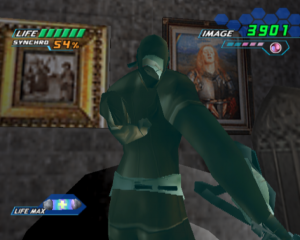

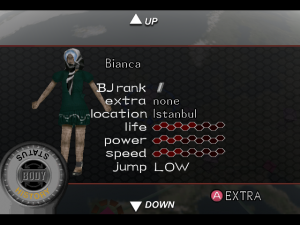

Shao, by contrast, does everything it can to remove that discomfort and make combat more natural. Many of the minor adjustments to how fights work are testament to that: brainjacking has gone from a level system to a sort of currency; the new Flare Count system gives players multipliers to their brainjack score for consecutive kills without taking a hit; individual bodies have their own synchronization rates (in lieu of ranks) and move sets to learn by gaining experience points from fallen enemies; mid-level checkpoints have been added to alleviate frustration; and special moves have either been reworked or significantly expanded upon. (Environmental and enemy designs have also been slightly altered, either to shorten length or to make pre-existing elements cohere with Shao’s changes.)

None of these changes would be possible without the change in perspective from first person to third. In fact, it wouldn’t be exaggerating to say that a lot of Shao’s focus stems from that one change. Where X’s perspective is loaded with connotation, Shao’s leaves the player with only the combat because that’s all the game wants to focus on. Pulling the camera out makes the world feel more open, allowing that world to center itself on combos and combat exhibition. Likewise, combat is no longer a struggle. Actions come out so effortlessly that Shao affords options that X never could. The general feel to combat remains the same between them – goofy wire fight scenarios – but in the former, it more clearly reads as such. That being said, the perspective shift is still somewhat undermined by the clumsy camera, something that was never really a problem with the original version. After a bit of play, it feels obvious that it was never designed as a third person action game, just awkwardly transitioned into one. Still, taken on its own terms, Maken Shao makes a lot of sense as a straightforward action title.

But Maken X was (or at least had the potential to be) much more than a straightforward action game. It’s also a story about an alien weapon that allowed its user to switch identities, and the young girl who used its power to save her father. Every part of the game is designed with that story in mind. In choosing to craft a satisfying gameplay experience above all else, Atlus failed to realize that a lot of Maken’s meaning comes from the very things they thought needed improving.

The predictable result is that Shao suffers for many of its changes. Some rob the game of meaning it might have been able to grasp. For example, discomfort with how a body controls or quirks in piloting a given character’s body no longer serve as revelatory moments. The camera’s third person perspective has already made it clear that this is not your body. What else is there to learn?

Other changes give mechanics a brand new meaning that Shao either can’t work with or can only work with in a very limited capacity. Flare Counts are one example. The way they encourage you to chain kills together makes you more eager for opportunities to fight enemies, which makes sense if one sees combat as an end in itself. For a game that laments modern crises like disease, war, and sectarian violence plunging the world into ruin, though, the mood Flare Counts establish runs counter to what Shao should be doing. (One might also consider the logical problems they create. How would someone like Kay have as much expertise with a sword (and so suddenly, too) as Shao’s introductory level implies?) No matter how individual alterations affect the game, their cumulative effect remains the same: a muted narrative that lacks whatever nuances X originally had.

What makes this especially strange are the changes Shao makes to the narrative. They’re not as drastic as the other changes Shao makes. The underlying story of Kay sacrificing herself to Maken and fighting Geist’s forces is fundamentally the same as before.

As minor as Shao’s modifications may sound, they result in a much more coherent story. No longer does Maken have to fumble about for meaning outside Kay’s psychological degradation. By explaining Psi and the concepts it draws on, and by giving the action a more palpable dramatic arc, it’s finally possible to see the world for what it is: one that suffers from its lack of spirituality, direction, and purpose. In addition, it’s possible to see that message more clearly reflected throughout Shao’s design. The more subdued voice acting lends characters pathos and helps them communicate their resignation to a hopeless situation. And primed with knowledge of the world’s suffering, the few levels set in cities (as opposed to monuments, prisons, dungeons, etc.) appear empty and devoid of people, save the soldiers roaming the streets.

Still, these changes can only go so far. Ignoring minor plot foibles, X’s failures stem less from an absolute lack of meaning and more from an inability to communicate whatever meaning it wants to communicate. The stand-out example is Hakke Dal’s comments about people fighting over race and religion, comments that aren’t grounded in any observable reality and thus come across as melodramatic nonsense. While the nonsense part may not apply to Shao, moments like Dal’s still feel unwarranted because they’re removed from the very thing they’re describing. The retranslated script of Shao certainly doesn’t help, either. If anything, it’s worse than X’s. At best, it’s stilted, and at worst, it very obviously rewrites scenes to say something different and ridiculous.

The other main issues are technical. Shao is an early PS2 game and it shows it, running at a lower resolution and with significant interlacing and anti-aliasing issues resulting in the infamous “jaggies” of the era. X has none of these problems, and ultimately looks cleaner.

Ultimately, what separates the two Maken games from Atlus’ other projects (both before and after Maken) is the level of clarity in their design. On one side are those that join narrative and gameplay together so strongly that there’s never any ambiguity about what the game is or what it’s trying to do: Shin Megami Tensei, Persona, Radiant Historia, etc. On the other side are those that focus on a satisfying play experience in lieu of any serious attempt at narrative. Many of Atlus’ early projects (like Jack Bros, Rockin’ Kats, Xexyz, etc.) fall into this category.

Where Maken is concerned, neither version accomplishes its goal of neatly slotting into its category of choice. This can either be because it’s not clear how the pieces should fit together, as is the case with X; or because the game alludes to narrative possibilities it has no interest in exploring, like Shao. Whatever the case, the two versions of Maken together have the ingredients they’d need to stand alongside the other games in Atlus’ library. On their own though, each is left chasing after completion they’re incapable of attaining.

Screenshot Comparisons

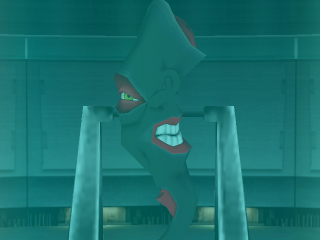

Enemies Artwork