- Eojjeonji Joheun Il-i Saenggil Geot Gateun Jeonyeok

- Storm

There are plenty of possible reasons why a video game may end up forgotten by the entire world. Some games are only released on obscure platforms, or only playable in arcades. At times a game just misses the trends of its times, getting ignored for being out of fashion before it’s even completed. Being produced by a small company that soon after goes out of business, thus rendering further re-releases unlikely, doesn’t work in a game’s favor either. (Not to speak of games that are just plainly so bad that they’re better not spoken of.) However, as a statistical glimpse on this site’s articles indicates, “obscure” very often means just “obscure to my region,” as most classic games exclusive to a Japanese release are automatically found to be widely unknown in the West.

Then there’s games where even a Japanese release would have worked wonders for their publicity. One of the regions whose gaming heritage is to a large part closed off to foreign audiences is mainland Asia. How many classic Chinese games that are not published by Panda Soft or re-released by Super Fighter Team do we even know? The Korean industry has become (in-)famous for the flood of more or less generic MMORPGs during the last decade, but before that, other than the odd Diablo clone or low-profile RTS we didn’t see too much out of there, either. Given that both countries’ gaming worlds are dominated by RPGs, one can see why publishers didn’t readily approach localizations of these titles. (Let’s not forget that even localizations of Japanese RPGs were somewhat of a rare commodity until the later half of the nineties.) Less text-intensive genres were affected regardless, probably because most games weren’t technologically on par with Japanese or Western developed ones.

Two of these games are Eojjeonji Joheun Il-i Saenggil Geot Gateun Jeonyeok (pronounced approximately like “odd-john-gee joe-‘en eel-ee sain-keel got cut-‘en john-yuck,” the title translates to “Got a feeling something good’s gonna happen tonight” and will be referred to in the following as Eojjeonji…Jeonyeok, which is the common abbreviation in Korea) and its semi-sequel Storm.

Almost all of the aforementioned obscurity factors apply to Eojjeonji… Jeonyeok, with the exception of the “plainly bad” one. Developed as the only game by a small studio called TG Entertainment at a time when sidescrolling beat-em-ups were considered dead and 2D games in general considered dying by the mainstream, and for DOS no less, Eojjeonji…Jeonyeok was never released outside of South Korea. Not exactly the best conditions for a game to get burned into the international awareness as a timeless classic, and it sure as hell didn’t. Heck, it doesn’t even have a title that can be spelled out in English in any convenient way. (One of its budget releases goes by the subtitle “The Fight,” but good luck googling for that.) At the same time, it was made in license to a popular Korean comic book series that sold more than a million copies. That one originally started in 1992, but got re-released in 2002 because of its constant popularity. Nonetheless, the rampant software piracy for which East Asia is notorious reportedly resulted in the game flopping, despite being played on nearly every other kid’s computer in the country.

The saddest part about all this: In many respects, it may well be one of the best 2D beat-em-ups ever made. It beats about every one of its significantly more famous “competitors” in terms of variety, dynamics and complexity. Not quite so in balancing, but more about that later. Much more important to point out is the lack of a coop mode. This big design mistake is really the sole factor that denies the game its exclusive place on the genre throne. Sure, the game is story-heavy for a brawler, and the requirements of the license probably didn’t allow the inclusion of a permanent companion in it, but was it really so hard to include a story-free mode as an extra? Quite tragic, just as much as the game’s incredibly obscure status.

Now that this shocking revelation is out of the way, let’s get into details. There are a lot of story sequences between stages, but the narrative feels put together rather loosely. After all, it’s adapted from an episodic comic book that needed to enclose its volumes to some degree, and of course lots of content got left out in the transition. Gunn Namgoong, the hero of the story, is on the way to his new high school, as he just transfered to put his recent history of student gang violence behind himself. In the subway, just as he spots his future love interest, his wallet gets stolen by a pickpocket, and he has to follow the evildoer. As it turns out, that one is tied to an organized crime syndicate, and his fellow thugs give Gunn no choice but to start fighting again. Most of the following stages very coarsely follow the events of the comic books, with the exception of three adjoined chapters that shed light on Gunn’s past, which is only vaguely alluded to in the original.

Characters

Gunn Namgoong

The protagonist of both the game and the comics. He once turned his former school into a hellhole of violence, but now he has woken up to the wrong of his ways, and promised his mother never to fight again. Of course, he still proves to be a trouble magnet, and the fighting continues.

Sogari

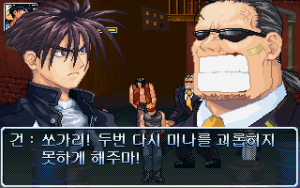

The sub-boss of a local gang. He first starts a fight with Gunn for hunting down one of his pickpocketing underlings. In later events, he constantly seeks out revenge for his initial defeat.

Eunhee Kang

A senior at Gunn’s new school, Bugye High, and leader of a group that tries to beat up Gunn on his first day. In the comics, he later becomes a constant rival in sports events, which are not in the game.

Euiwook

An original character in the game’s flashback levels. He is the “captain” at Gunn’s former high school, Jijon. That is, until he gets beaten up by him.

Sunwoong Min

Also makes his appearence in the flashback. Following the protagonist’s reputation as a fierce bully and new captain of Jijon High, he seeks him out to have a match with him.

Jin Ha

The last of the opponents in the past episodes. She once had helped Gunn when he got beaten up by bullies as a little kid, so her encounter reminds him that life really is about finding friends instead of fighting, which causes him to change his attitude.

Mun Jaewoong

Another of the villains from Sogari’s gang, he kidnaps a friend of Gunn’s.

Seoho Son

An odd new student who makes acquaintances by street fighting. Needless to say, he becomes one of Gunn’s best friends.

Jongsuck Park

The new brutal captain of Jijon High, obsessed with fighting Gunn to clear “his” school of his predecessor’s reputation. To lure him in, he kidnaps girls from Gunn’s school, including his love interest Seunga.

Seunga Min

Living at the same boarding house as Gunn, and his would-be girlfriend. Naturally, she gets into danger half the time to be saved by him. In the game, she only appears in cutscenes and on the level-up screen.

Kim Mina

Another of Gunn’s friends, a girl with a troubled past. She once belonged to the band of thieves Gunn constantly gets into quarrels with. In the comic, she’s a strong and interesting character most of the time. In the game she’s reduced to her role as yet one more damsel in distress.

Taehyung Kim

Gunn’s former classmate from Jijon High. He seeks out his old friend for help against the school’s new tyrannic captain. Also exclusive to cutscenes.

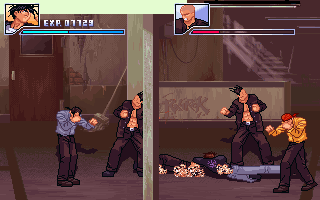

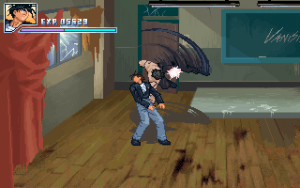

Upon the start of the game (and without a manual), one could easily come to dismiss it as a boring, typical Final Fight clone. After a few pages of story, with redrawn images by the original comic’s author, Gunn finds himself walking through urban streets beating up some punks. The only means of attack seem to be a single series of punches, as well as a kick-combo, and two similar jump attacks. There’s no running, and the walking speed is pretty slow.

Then you reach the end of the first short substage, and everything changes. A level-up screen appears, with quite a lot of things to upgrade, but the only one that is affordable with the experience points gained by now is the first tech upgrade. Now things start to get interesting. All of a sudden you can dash and run, both combined with new attacks, grab enemies for a decent selection of grapple moves and get-up attacks after getting beaten down. Maybe most importantly, it’s even possible to crouch down to avoid hits (which can also be paired with counter attacks later.) The real fun begins when one drives enemies into the corner of the screen, since there’s a ton of possibilities for juggles and ground hits. There aren’t many beat-em-ups that can even approximately rival Gunn’s repertoire at this stage, other than Double Dragon Advanceand maybe the later IGS games. Once fully upgraded to level 4, the move list puts most fighting game characters to shame.

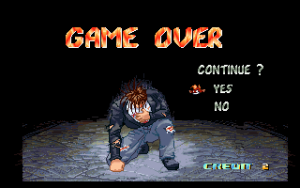

If that level is ever reached, that is. Tech is not the only stat waiting to be upgraded—one gets to choose between health bar extensions, attack power enhancements, speed ups—even health regeneration and credits are bought with the hard-earned experience points, as there are no healing items during the stages. Choosing wisely is an absolute necessity, because this game is hard. In later stages, it’s not unusual to get the initial level 0 health bar depleted to nothing in two or three hits. Even with the maximum health at five bars, dead comes quickly. Enemies react a bit slowly though, and wait quite a bit before attacking. This could be judged as weak AI, but it is really only for this fact that the game retains its balance at least to some degree. As soon as enemies do attack, they start ganging up on Gunn, and in later stages, they’re usually paired up to complement each other’s weaknesses. As the number of enemies is fixed, there’s also no room for grinding either, with one exception: Sometimes a near-death experience will make an enemy blink red, which means he can only be taken out by knocking him to the ground once again. This is the only opportunity to milk enemies with cautious attacks for hit-EXP.

Eojjeonji…Jeonyeok’s difficulty even gets a bit unfair during the latter half of the game’s nine stages, with sections that drag on pretty long—the worst one with a boss right at the end and without a checkpoint in between. A defeat always results in a restart at the last checkpoint, and while stats can be upgraded at any time, the same is not true for health recovery. This makes leveling even more strategic, as it practically forces the player to conserve health bar upgrades for these insane stages, as they also fully restore your life bar. The final boss then is almost positively invincible without exploiting a glitched infinite combo. The only other critique left about the gameplay would be the relatively event-less stages, devoid of any item pickups, traps or background animation.

The characters are drawn and animated well, though Gunn’s standard walking cycle looks a little odd. The backgrounds show beautiful pixel art most of the time, but there are not many interesting things to see, as most stages are built on genre staples like city streets, forests, schoolyards, parks, bars, etc., and there’s not much going on in them other than the fighting. What stands out is the constant advertisement for Ragnarok, which is not yet the popular MMORPG, but the then-latest comic book series of the same author and the planned but unreleased single-player RPG by TG Software.

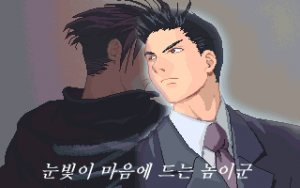

Most enemies are rather cliched, representing your usual selection of punks and thugs. You’ll also get the chance to beat up some school girls. (Yeah, Gunn is a real hero.) All in all, the collection of about 20 enemy types is not too bad, but also not very impressive. This is not counting strict palette swaps, but some look samey, nonetheless. The cutscenes are all drawn very well and displayed in 640×480 resolution. They constitute a serious update compared to the original comic’s black & white drawings, but that doesn’t change the fact that they’re just static images with a lot of Korean text that won’t be of any use to most Western players.

The music tunes are just great. The arrangements are quite typical for 90s synth CD soundtracks, but most tracks do a very good job to get you hyped up for the action. The sound effects deliver their message, as well, though they are plagued by that genre-typical illness of becoming extremely repetitive over the course of the game.

Eojjeonji…Jeonyeok is the kind of game the expression “it’s a shame” was made for. It’s a shame that most of the gaming world didn’t even hear of its existence, it’s a shame that one of the potentially best beat ’em up games was refused a multiplayer mode, and it’s a crying shame that its underwhelming commercial success should cause TG Entertainment to fold, leaving the developers to produce its successor under sub-optimal conditions. But more of that in the following chapter…

There’s also a demo version of the game, but it lacks music and only showcases some slices of different stages. It does have the courtesy of starting players at tech level 1 rather than 0, though.

The Comics

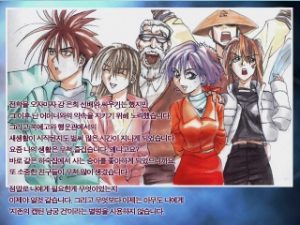

Released in 1992 as the debut work of artist Lee Myungjin, Eojjeonji… Jeonyeok soon became one of the most popular comic series for teenagers in Korea. It contains a lot of action scenes, but other than the game is equally a love story, sports and racing comic, as well as a comedy. In fact, only five of the nine volumes even contain scenes represented in the game. A lot of characters got axed, mostly those whose main purpose was comic relief. Also, Kim Taemin, Gunn’s best friend in the comics, who would have made a great 2nd player character, isn’t so much as mentioned in the game’s story. He appears in a few (unimportant) cutscene images, though.

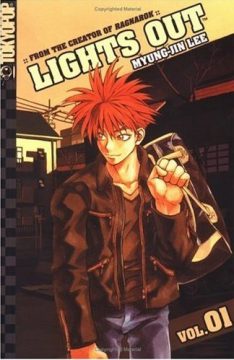

In 2005, the popularity of Ragnarok obviously was enough to arouse interest in Lee Myungjin’s older work, thus the series saw an English release by Tokyopop under the title Lights Out. Even without having read the English comics, however, the fact that the translator didn’t even manage to distinguish between Gunn’s personal and family name (it’s one of the rare Korean two-syllable family names), doesn’t inspire much confidence. The series went out of print a long time ago, and some volumes are hard to find nowadays.

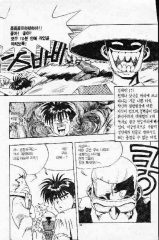

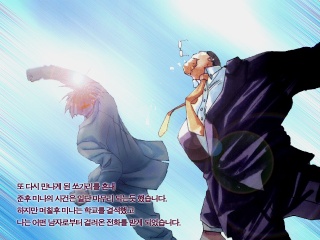

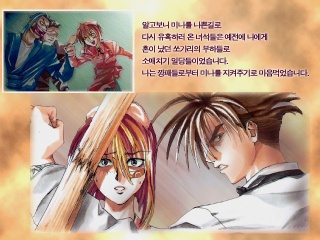

The drawings themselves are a mix of the semi-realistic style that also dominated Japanese manga prior to the mid-90s and occasional exaggerated facial expressions, bordering on super deformed style, akin to Tooru Fujisawa’s GTO series. Most of the game’s cutscenes consist of upgraded images from the comic.

Comparisons

Comic

Game

Comic

Game

Comic

Game