You wouldn’t think so by glancing at it, but Folklore is actually all about Halloween. Or rather the closely related but much older Celtic festival of Samhain, which occurs on October 31st and marks the end of summer. Celebrated over several days building up to the night itself, and taking on a festival of the dead atmosphere, it’s said to be when the spirit and corporeal worlds are at their closest, and so the living wear masks to ward off the spirits. Or so the legends go. In the world of Folklore, a mysterious death occurred 17 years ago on the night of Samhain, with several more deaths over the following days, and it’s up to the player to unravel this mystery while visiting the Netherworld and communing with the Faery folk and spirits of the dead.

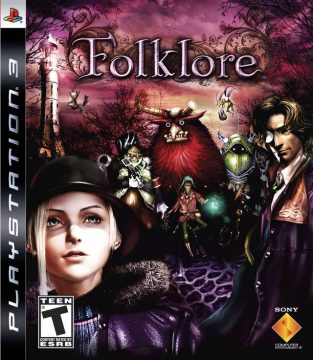

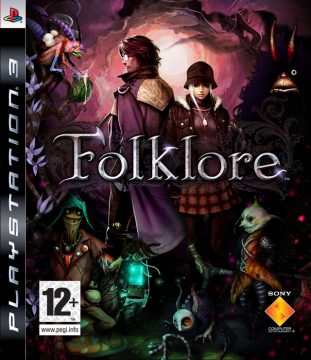

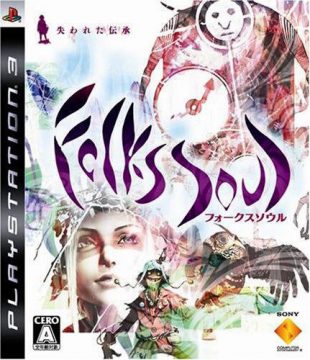

Developed by Game Republic and released in 2007, Folklore exemplifies many of the problems the Japanese games industry has faced that generation. Folklore was a game which danced through all the rings demanded by a Western audience, yet still didn’t entice them. It was an expensive game with enormous production values, published by Sony, headed by industry veteran Yoshiki Okamoto (Time Pilot, Street Fighter II, Resident Evil), received generally good reviews, but ultimately failed at retail. It was visually beautiful, orchestrally enchanting, and with a substantial combat system, unfortunately serious flaws made it something of a curate’s egg. Whatever the reasons, no one bought it. The planned sequel (rumoured for PSP) was cancelled, and today few talk about Folklore, leaving it overlooked and nearly forgotten.

Undoubtedly the best aspect of Folklore is its rich aesthetics, distinct styling and game world, an intriguing Japanese slant on Celtic myths which feels wholly original. Taking place in the real-world village of Doolin in Ireland, players control both Ellen, a young woman searching for her past, and Keats, a cynical journalist looking for his next big story. Both are drawn to the town by a mysterious communiqué and find themselves involved not only in a 17-year-old Samhain murder mystery, but a conflict that has lasted for five millennia within the spirit Netherworld. Able to travel into the Netherworld, which few humans can, the two characters must explore the five Netherworld Realms, penetrate the Netherworld Core, and all while regularly switching back to the real world to disentangle the problems of those in Doolin. The village itself is overcast and grim, authentically recreating a winter’s day in the UK, whereas the spirit world is bright and vibrant, even in its most hellish or darkest of places. The stark contrast between the worlds, and the quirky nature of the Netherworld itself, has an almost Tim Burton vibe to it.

Characters

Ellen

Raised in an orphanage because her parents seemingly died when she was a child, Ellen is drawn to Doolin because of a letter claiming to be from her mother. Once there it’s soon revealed that she possesses a special ability to commune with the spirits and, guided by helping figures, is given a cloak allowing entry into the Netherworld. She agrees to help the Faery Lord in the Faery Realm so as to restore her memory. There are various costumes she can find which grant status boosts.

Keats

A skeptical journalist who doesn’t believe in the Netherworld or Faerys, and yet writes for a second-rate, failing occult magazine known as Unknown Realm. Receiving a mysterious phone call from a woman in Doolin, claiming Faerys are about to kill her, he puts off his current article to investigate. Although sometimes unhelpful towards to Ellen, and seemingly siding with the Faery Lord’s enemy Livane, Keats actually acts as something of a guardian to Ellen.

Mechanically the game is divided into two styles, joined together via some rather inventive comic book cut-scenes. It’s a shame that some reviewers chose to criticise these, since they help cement Folklore‘s already unique style. First you wander around Doolin, speaking with people in the village, collecting mementos of the deceased so as to activate portals to the Netherworld, and taking on optional side-quests from the pub landlord. During the day you’ll only find humans around the village, whereas the night is the only time you’ll have access to activated portals, or can chat with the half-live inhabitants of the pub. Half-lives in the game are bizarre looking, supernatural beings created from a person’s strong desire or wish. They too offer a selection of side-quests, though you can only ever have one active at a time. Calling any of these “quests” is a misnomer though. All of them warp you to the start of a specific realm, and completing them merely involves getting past a few screens. You usually don’t even need to fight any enemies, you can just run past, reach the end, and a cut-scene will automatically play showing its resolution. Frankly they seem tacked on and redundant. Some have described Folklore as an action based JRPG because it features NPCs and dialogue, side-quests, and an EXP system where your characters can level up to increase their HP, plus a diverse inventory of weapons and key items. Which is a cute idea, but anyone going into the game thinking this will be sorely disappointed.

The second portion of the game, which takes place within the Netherworld Realms and constitutes its bulk, is best described as an action brawler. Although missing the ability to jump, it’s comparable to the classics Final Fight and Altered Beast, and more modern updates such as Devil May Cry and Heavenly Sword. You move with the left analogue stick and control the camera with the right, while the four controller buttons each represent a customizable attack. Here is where things get interesting. When wandering around the action areas you’ll fight Folk, the name given to the supernatural creatures in the realms. Each is based on a real-world myth (such as the Cait Sidhe), and after damaging them enough you can latch on using R1 and pull the soul from their body. It’s a bit like Ghostbusters, where a beam of energy connects you to their body and – in what must be the best implemented use of Sony’s SIXAXIS – you flick the controller to suck it out. It becomes intuitive and quite satisfying to jolt the little blighters out of their bodies. Once an enemy is absorbed it can then be used as a weapon, even the minibosses, by assigning it to one of the face buttons. Certain bigger enemies and bosses require a special technique to absorb, as shown by the colour of their partly protruding soul. For example a blue aura means you need to rotate the controller left and right, whereas orange means you need to shake furiously.

Some Folk allow short-range attacks, like a sword swing, whereas others offer projectile attacks or status changes. Which again may imply some kind of action-RPG style, but the entire thing feels more like a brawler with customisable attacks. All Folk fall under a specific element or type of action (ie: Fire, Heavy Damage, Shield and so on), while some enemy Folk have specific immunities and weaknesses, requiring clever use of those in your inventory. Ellen and Keats control entirely differently when it comes to combat and each has their own unique selection of Folk to collect – while they share a lot of the common Folk, they each tend to use them differently. Attacking also draws from a common energy pool each character has, so you can’t just spam your most powerful move. With Ellen, her energy recharges slowly when not attacking, and with Keats it recharges in an instant if you wait a few seconds.

Keats is definitely the best character, since all of his Folk focus on either attack or defence, and his elemental attacks are neatly categorised into Fire, Ice and Earth. They’re also almost all direct control attacks, with Keats manifesting the Folk in front of him to use as a weapon. Hawk for example is a bayonet carrying soldier, who can be used directly as a blade. The fact that his energy recharges in an instant also allows him to attack more frequently, making him the brute force option. In contrast, Ellen is a terrible character to play as, since most of her Folk are autonomous – with Hawk, he manifests in front of Ellen and goes off to do his own thing, which is usually run against a wall until he disappears and not bother attacking the enemy at all. This is hugely frustrating. Of the Folk which Ellen has direct control over, many of those merely affect an enemy’s status, such as putting them to sleep, paralyzing them with goo, or charming them. These are almost always useless, except in the few specific cases where an enemy is only vulnerable if first disabled. He slow energy recharge makes this all worse, since when you do finally have a strong Folk to attack enemies, they eat up so much of the energy bar you spend most of the time evading waiting for it to recharge.

In addition to Doolin are the five main Netherworld Realms. There’s the Faery Realm, conjured from mankind’s belief in a fantastical afterlife, and presided over by the Faery Lord. It’s filled with bright colours, flowery pastures, and quirky Folk characters. Second is Warcadia, a realm formed from mankind’s obsession with war, and resembling set-pieces from various conflicts. Most of the Folk within have some kind of military theme. Next is the Undersea City, a fairytale world deep within the oceans, filled with marine based creatures. This is definitely the best world, both in terms of stunning watery visuals, and the layout and types of Folk you can capture. The fourth is The Endless Corridor, featuring a visual style like a cross between HR Geiger, MC Escher, and Tim Burton. Unfortunately it’s probably one of the two most frustrating realms since there’s no map and the entire thing is an endless maze, navigable only by following the clockwork enemy Habetrot. The fifth area, HellRealm, is perhaps even more frustrating, since it features the game’s toughest enemies – all of whom are major damage sponges – and some excruciatingly long, mandatory elevator rides along with said enemies. The final area, or set of mini-areas, is the Netherworld Core, which initially resembles a well cut English lawn, and then an icy maze of passages.

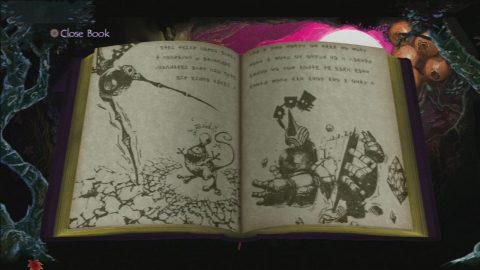

It cannot be overstated how fantastic the world of Folklore is. It really is a joy just to wander through and witness. Nick Des Barres in Play Magazine described how it was one of the most beautiful games of this generation; it was this generation’s Ico. Comparisons to Ico are open for debate, but he was unequivocally correct in describing it as the most beautiful game – certainly at that time. There is more colour in a single static screen than some game developers will use in their entire decade-spanning existence; more colours than the HD capture devices we used for this article can accurately reflect. Every Folk creature has its own hand-painted and scanned in portrait, with an amusing description alongside which are well worth reading through. It enriches an already resplendent mythos. As you transcend steps towards the Faery Lord’s hall butterflies of blazing light erupt from your feet to the sound of children’s laughter. Rather than tutorials the game features a series of Faery books to find, the pages of which depict stories of creatures in monochrome ink. More than mere decoration, these explain the weaknesses of the various enemies – it’s both subtle and ingenious, a minor point but one of such extreme elegance that it’s shameful how poorly other developers convey the same information. In so many ways Folklore‘s presentation is timeless, and much like the later released El Shaddai: Ascension of the Metatron, it will continue to be sumptuously exquisite in years to come.

So far the game should sound well conceived and with extremely high production values, seemingly with few faults. Unfortunately, this is also where things start to unravel, because the comparisons to El Shaddai can continue with the combat. Although it doesn’t suffer from the same insipid, limp and wholly worthless gameplay that El Shaddai has, Folklore does seem to be a victim of its own ambitions with several crippling flaws.

The combat, which is what you will be doing 90% of the time, just doesn’t work as well as it should. For starters the Folk system tends to suffer from arbitrary Pokémon syndrome. There’s well over 50 Folk you can capture across the realms, and all of them can be levelled up by fulfilling certain conditions (feeding them special items, defeating a certain number of a specific Folk using them and absorbing a number of specific folk). The levelling up process is tedious at best, since you need to bring specific Folk to specific areas, and constantly switch between them. The problem is there’s only a handful of Folk which are genuinely useful, meaning you spend a lot of time struggling with the slower or weaker varieties just to strengthen them. You can ignore levelling these, of course, and just focus on your favourites, but towards the end of the game are enemies, especially mini-bosses, which can only be beaten using specific Folk, so it’s best to level them up. One benefit of being an older PS3 title is that it lacks Trophies – had they been implemented, no doubt you’d be required to max out all your Folk for a little digital medal. The lack of Trophies lends proceedings a kind of purity.

You can still ignore levelling, and just play very carefully when your weak Folk are needed, but the combat itself isn’t nearly as smooth as descriptions make it sound. While you can customise the four face buttons to use any collected Folk, none of the attacks really combo into each other. You use one on its own, and there’s an awkward moment when you switch to another. So you’re better off just spamming one attack over and over. Combat feels stilted and awkward – it’s definitely more like Heavenly Sword than Devil May Cry in terms of precision. This is worsened by the need to wait for your energy bar to recharge. Often you won’t even have enough energy to switch Folk, resulting in a buzzer sound and no action taken. This is where the game ends up eating its own tail: because moves don’t flow into each other very well, most players will spam the strongest attack, so to balance this you can’t attack continuously. If you’re playing as Ellen you’re also gimped by having a lousy selection of Folk available to you. Then there’s the fact that later enemies are brutally cheap, able to indefinitely stunlock you using electro and paralysis attacks, and are relentless in their pursuit. The HellRealm is aptly named in this regard!

Best boss battles ever

Surprisingly, as tedious and repetitive as the regular combat is, the boss battles are hands down some of the best you will ever find in a videogame. Each of the Realms is tormented by a Folklore, a large and malevolent creature which needs ousting. All five of them are excellently conceived. Each takes the form of a “combat puzzle”, with a series of weaknesses which need to be exploited through clever combination of Folk abilities. Take the first boss, as one example. When he starts sucking you up with tentacles, you need to use one of your Folk with a spiked body – he’ll suck the Folk up instead, hurting himself. While stunned, you need to use a slashing Folk to cut the tentacle, before switching up to a heavy hitter to attack the boss itself. All of the boss battles play out fantastically, showing that the design staff really knew what they were doing. They’re fun, require quick reflexes and some intelligent planning. The terrible shortcomings of the regular combat, in contrast, seems the result of a lack of time when trying to finish development. Since the easiest thing to finish off a level is just throw a few more enemies in and hope for the best.

All of the above problems would be tolerable, were you allowed simply to choose Keats and play through the game normally. The combat is a bit dull in places, but he’s good enough to brute force your way through the more arduous sections. Unfortunately to reach the end you’re forced to play through as both Keats and Ellen. To access Chapters 6 and 7, you need to beat Chapters 1 through 5 with both characters. Keep in mind that these are identical to each other – sure, some Folk are different, as is NPC dialogue and the story, but mechanically you’re in the exact same environments, dealing with the exact same stilted combat. Most games usually allow you to finish them once before introducing NewGame+, but here you’re forced to play both concurrently. This is a maddeningly stupid decision, especially because Chapters 4 and 5 are such a tedious grind with cheap enemies. Later foes also tend to be massive damage sponges, even with your Folk maxed out and the best element being used, leading to a feeling of malaise. Sometimes it’s akin to using cotton wool to carve marble, and while not necessarily difficult if you’re methodical, combat drags on unbearably.

In a sad way you can understand why Game Republic did this. Given how expensive the game is, it needed to deliver an acceptable play time. If you only needed to play the first five chapters once, without grinding most players could probably rush through in about six or seven hours. This doubles to 14 hours thanks to the mandatory replaying, on top of which you can add another four or so hours if you max out your Folk. With Western developers producing high-definition epics spanning 40+ hours (usually consisting of utter tedium, it must be added), there’s a tangible sense that Game Republic were desperately trying to add length to their creation, but only diluted the quality in the process.

The events in the story don’t quite live up to the majesty of the setting or source material either. The character who died 17 years ago, and is introduced early, is a terminally ill boy named Herve, whose father is a writer named Renaldo. While it’s feasible that a Spanish writer would live and work in Ireland, it’s never really explained why he’d choose to come to a sleepy little village when his son is so sick. Surely a city with top medical facility would be better? Instead, the boy is cared for in a makeshift clinic in the nearby church. There are plenty of other elements which are flawed too. In fact, some aspects of the ending (notably the explanation regarding Ellen’s mother) make no sense whatsoever. There is a rather fun twist right at the end, though, if you can work it out.

It would be comforting to think that Folklore‘s low sales were entirely due to its inherent problems. But the sad fact is, it’s probably just as much to do with its unique style and flamboyant creativity. Your average, PS3-owning, Call of Duty-playing dudebro isn’t interested in a game with a Celtic theme, set in a quiet Irish village, where men in strange clothes discuss Samhain and visiting the Faery Kingdom. Nintendo can get away with creating whimsically themed games, because in addition to its hardcore adult followers, its sales are boosted by the children’s market. Folklore is too dark for kids, but isn’t likely to appeal to many adult gamers either. It seems Game Republic really just can’t catch a break, because their later game, Maijin: The Forsaken Kingdom, also did badly, and now its laid off its entire workforce. Yoshiki Okamoto has even stated that he’s retired from game development, and that Japan is doomed. As he explained: “We’re probably heading toward the end of an era of Japanese game developers making successful console games like in the West.” To what extent competing with the West caused the problems for Folklore is uncertain, but it’s regrettable to see how close the game came to being a genuine classic.

If you have the patience to put up with the sometimes terrible combat, there’s a really charming creation within; masterful, though not quite a masterpiece. Definitely better than El Shaddai though.

Online components

Folklore also features some interesting online components. There’s a dungeon editor where you can create your own labyrinth and populate it with in-game enemies, to share online. Too bad the entire thing is absolutely terrible. You can only access the mode while signed in to PSN, which is annoying and limits its lifespan, and once inside it’s apparent that all the dungeons are identical. The rooms and corridors all look the same, making them very repetitive, while the enemies within each room suffer from the same stifling combat as the main game. It allows you to grind for character EXP, but without the beautiful environments or promise of story elements, it’s excruciatingly boring.

There’s also a lot of DLC. There are six main mission DLC packs. These add background details to certain story arcs, as well as offering special Folk and costumes. They’re also available in the US, including combinations of them as bundles. n addition to charged mission DLC, there are some free DLC packs too. In the UK you can get the Malion Folk, from the “Design a Folk” competition, and another called Pigly, which is a cross between a pig and a butterfly. In the US there’s a free Folk called Quasarilli you can download, and some Christmas themed costumes. Unfortunately the UK and US DLC are exclusive to each region, and incompatible with copies of the game from other regions.