Troika Games was a short-lived game development company started by former Black Isle and Interplay employees: Leonard Boyarsky, Tim Cain and Jason Anderson (the latter two would later join other post-Interplay companies like Obsidian and inXile while Boyarsky went on to Blizzard). The studio’s name – which referred to the fact that it was created by three people – would unfortunately become prophetic concerning their output as well, as Troika only made three games: Arcanum, Temple of Elemental Evil and Vampire – The Masquerade: Bloodlines. Each of those titles gained a large cult following due to their deep, complex and non-linear RPG gameplay, while also receiving significant criticism for a large amount of bugs – Troika’s games all were released in a very broken state and the official patches couldn’t always fix all the problems.

Arcanum, the first of Troika’s games, clearly betrays its lineage from the early Fallout games. It can be seen in everything from the way the characters move over the map to gameplay mechanics like action points, intelligence significantly affecting dialog choices up to making ‘stupid’ characters incapable of conversation more complex than ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘ugh…’, and the ending divided into multiple segments related to different characters and locations, reflecting changes that happened as a result of your actions. There are also direct references, like a two-headed cow in the town of Tarant, a quest concerning a gem of water purity and a person not allowed to go back home after being influenced by the outside world, just like the hero in the original Fallout. While Arcanum is still different enough to become more than just Fallout with steam engines instead of vacuum tubes, it’s obviously a spiritual successor in many ways.

The old Fallout games were known for their non-linearity – there were almost always multiple ways of solving quests, character building wasn’t restricted by classes and the world reacted to your choices. Arcanum takes this ‘choice and consequence’ aspect even further – players can freely develop both their skills (also affected by apprentice, expert and master training received during the course of the game) and their stats. The choice between magic (or ‘magick’, as the game clearly prefers Aleister Crowley’s spelling of the word) and technology is an important part of the game too, and characters will not only treat you differently based on your morality and reputation but also depending on race – humans, halflings and half-elves don’t face too much discrimination, dwarves and elves dislike each other, gnomes managed to get accepted in society after years of hatred and everyone is prejudiced against half-orcs and half-ogres. Arcanum tries to be a sort of virtual tabletop – a game where different choices result in a different game. It mostly succeeds.

You start Arcanum as the sole survivor after the crash of the dirigible IFS Zephyr. At the crash site, a dying gnome gives you a ring and tells you to ‘find the boy’. Assassins try to kill you, and then you meet Virgil – a man who claims that you are a Living One, a reincarnation of the elven wizard Nasrudin who lived 2000 years ago. While all of this sounds like a generic ‘chosen one’ story, as you uncover the game’s mysteries (which might require several playthroughs as some information is available only to characters of a certain alignment) it becomes clear that it’s anything but. There are some major twists near the game’s ending, culminating in the final encounter with the antagonist, which is less about stopping a world-conquering evil and more about sorting out thought-provoking philosophical differences between the characters. Like in the first Fallout, it’s even possible to either join the enemy or convince him to give up without fighting.

While the plot and writing are good, the best part of the game’s narrative is without a doubt the world building. Arcanum explored steampunk (and not the ‘just put some gears on it’ kind) and the conflict between magic and technology before they were done to death but – more importantly – it puts a lot of thought into how those things would affect a fantasy world. This is a world were mages have to sit on the back of a train because their power would interfere with the engine. The game takes place at the turning point of history, and the story of the kingdom of Cumbria shows what happens when parts of society desperately cling to tradition and reject scientific progress. The prosperity of technologically inclined humans leads to a decline of the typical fantasy races like dwarves and elves, and the isolationist mages of Tulla. Political conflicts concerning orc laborers, half-ogre breeding and the Industrial Council reflect historical issues from the late 19th century: trade unions, eugenics, democratization of governments.

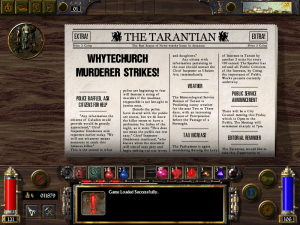

The graphics, while dated even at the time of Arcanum’s release, have some really good art direction – this is especially noticeable with books, newspapers and the map the game uses for fast-travel. The soundtrack consists mostly of slow-paced, slightly melancholic string quartet music (with an exception of a more tense track during combat). It’s an unusual choice for a soundtrack but it works very well given the game’s setting and atmosphere.

The story of Arcanum‘s world is told by the spaces you visit as much as it is conveyed by words. While the game never holds your hand the way modern RPGs do with their quest markers and other navigation aids, once you familiarize yourself with each area, you’ll never have a problem finding your way, as the towns are laid out realistically, often with distinct poor, rich, commercial and industrial districts. Buildings are similarly well thought-out with shops, train stations, factories, simple houses for the common folk and huge mansions inhabited by the rich or royalty.

Unfortunately, things get dull when you leave the towns and wander into the dungeons – and there are many of those. When the game tells you to explore mines, sewers, forests or ruins, get ready for slogging through repetitive dark corridors filled with traps and repetitive enemies (bonus points for creatures made of stone or fire – the former damage your weapons while the latter damage both weapons and armor). There’s just nothing interesting about most of the combat-heavy areas – just the same enemies (with occasional size and color variations), same battle music and same boring corridors. It would help if combat itself was interesting but it isn’t – there’s a choice between Diablo style real-time combat, which sucks if you don’t play a melee-oriented character and turn-based combat with action points, which is only marginally better because the whole system comes down to being fast at doing damage and maybe getting behind enemies for backstab bonus. Thankfully, the balance is so broken there are many ways of creating absolutely overpowered characters without compromising roleplaying aspects, so it’s possible to get the fighting over relatively quick. It still remains a mystery why Troika didn’t opt for real-time with active pause, like in Black Isle and Bioware’s Infinity Engine games.

Probably the most annoying aspect of the combat is the AI. Neither the enemies nor the autonomous companions use anything even resembling tactics – but they’re pretty good at ruining yours as they’ll happily get into combat when you try to be stealthy, burden themselves with junk objects and walk into traps. Their stupidity can even ruin potentially cool mechanics like item identification as they’ll happily put on unidentified clothes and keep wearing them even if they’re poisoned, cause critical failure or just damage them on every turn. There’s a recruitable dwarven mage somewhere in the game, who needs more magic energy for each spell due to his race, and of course he keeps turning into a fire elemental, exhausts himself after a few turns and falls unconscious after every single battle. Good companions get angry if you commit evil acts, and sometimes they think it’s evil to attack non-hostile creatures even if every single one of those creatures turns hostile the moment you enter its line of sight.

Unfortunately, no character build can fix some of the puzzles in the late game, which can get just as annoying – at one point, the player even has to solve an obtuse pressure plate puzzle just so he can find hints and an item needed to solve another obtuse pressure plate puzzle.

As with Troika’s other games, Arcanum‘s problems further include many technical issues. The interface is rather clunky, and aside from giving you an ability of mapping commonly used spells, items or abilities to hotkeys, it cannot be customized. Pathfinding is pretty bad, especially when travelling using waypoints on the map, as the game will often tell you that your path is blocked when you put waypoints too far from each other, even if you’re walking in a straight line through an empty field. Probably the funniest bug is the one that happens near the end of the game – you’re given a chance of recruiting a supposedly extremely powerful character whose level is the maximum the game allows. This character then keeps dying to random enemies because the developers actually forgot to invest his skill points into anything and there’s no way to manually distribute them for your companions.

Does this mean that Arcanum is a bad game? Not really. It’s just that it lies on the extreme end of the spectrum which runs between “boring but polished” and “ambitious yet buggy”. Arcanum is very ambitious and very buggy. It’s a logical evolution of 1990s computer RPGs, amplifying both their strong and weak points. At its best it’s a narrative-heavy game which – provided you raise your persuasion skill – lets you skip a difficult dungeon by making a different adventuring party retrieve the item you need and bring it back to you. At its worst it’s a tedious struggle against the enemies, the interface and the AI. It’s a game that was clearly designed with a hardcore audience in mind. It has everything CRPG fans love (complexity, non-linearity, dice rolls, mod support).

Despite its many issues, Arcanum is still a game worth playing. When it comes to narrative freedom and atmosphere it’s one of the best and it deserves its place among the likes of Fallout, Baldur’s Gate II and Planescape: Torment. But when it comes to dungeons, combat mechanics and general polish, it’s very lacking. Still, the good far outweighs the bad and almost anyone who has played the game remembers the story and the world even quite some time after playing the game.

Troika made a few official modules for the game, which could be downloaded from the official website. One of them, Vormantown, was bundled with the main game and it’s a short, combat-oriented campaign designed for online co-op. It plays as bad as it sounds, especially given how multiplayer Arcanum disables the overworld map and forces all combat into real-time mode. A full-fledged sequel titled Journey to the Centre of Arcanum using Valve’s Source engine was planned but unfortunately never created. As for now, Arcanum fans can only hope that the modern resurgence of isometric RPGs will either resurrect Arcanum series the way it brought back Wasteland and Shadowrun, or spiritual successors of Torment, Baldur’s Gate and Ultima. The ideas behind Arcanum are just too interesting to fade into obscurity – they just need to be refined, polished and improved.

Links:

Terra Arcanum – the biggest Arcanum resource; includes essential mods which fix many of the game’s problems

Arcanum at Good Old Games

The rise and fall of Troika – the history of Arcanum and its developer