While Westone are best known for their Wonder Boy/Monster World series of action-RPG platformers, they’ve dabbled in plenty other genres over the years. One of these was Willy Wombat, an overhead action game originally conceived for the SNES before moving to the Saturn. It was made specifically as a Sonic-esque game for Hudson Soft to release in North America, but ended up coming out exclusively in Japan. That’s a shame, since it’s a solid adventure containing some interesting ideas mixed with frustrating issues.

Willy Wombat is an enforcer working for the utopian society Prison, who suddenly leaves one day in search of the land of freedom. Guided only by a message discussing something called the Miracle Gems which might hold the answers he’s looking for, he wanders the outside world whilst being pursued by a trio of fellow enforcers charged with his capture.

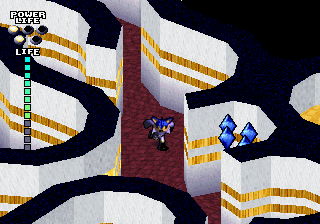

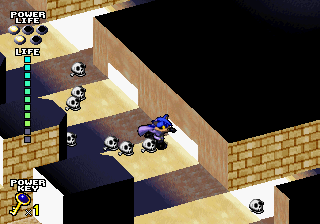

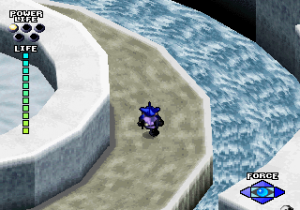

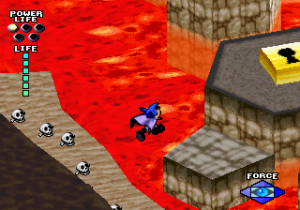

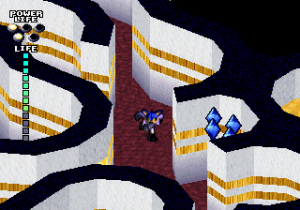

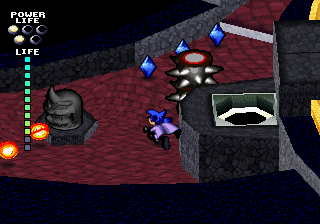

This is a stage-based action game where your goal is to reach the end of each level. The characters are rendered with sprites, while the environments are 3D. You can walk, jump, dash by double-tapping the D-pad, and fend off enemies with short-range swipes or throwing your two boomerangs to hit them from afar. These boomerangs are useful for clearing out numerous enemies, as well as grabbing objects and hitting statues, but be careful because they won’t deal any damage coming back.

You’re also able to turn the camera with the shoulder buttons, which makes aiming your shots easier since Willy throws in the direction he’s facing and helps with better navigating the levels. That’s especially important because your view is often obscured by cramped hallways and other objects, with no other way of seeing Willy or anything else without regularly adjusting the angle.

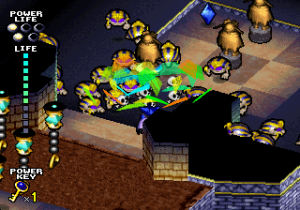

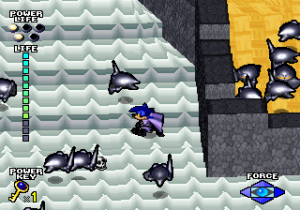

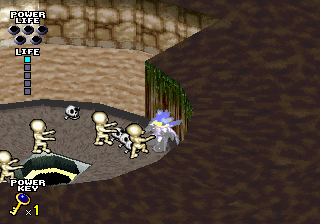

You’ll definitely want a clear view when dealing with the hordes of enemies populating levels. Sometimes you stumble across them unseen and can take them out in advance, but many situations have them appearing from trap floors and walls that force you to react fast. They’re always moving towards you, only occasionally stopping for a second or two, and it’s easy to get overwhelmed whilst trying to move and attack.

This isn’t inherently bad, as it induces a sense of panic that fits the emotion of exploring hostile uninhabited wastes. But it’s a panic that turns to irritation when compounded by numerous design choices. Enemies that take multiple hits won’t get stunned by your attacks and will keep chasing you, and you have such a bafflingly brief window of invincibility when hit that you’ll lose a ton of health if you get mobbed.

Worst of all is the complete lack of checkpoints, meaning that death throws you back – not to the map screen – but the main menu. This means you’ll have to reload your save, and potentially be forced to repeat a stage or two if you haven’t saved in a while. When these levels are full of tricky traps, navigational puzzles and crowds of enemies that can quickly kill you, it becomes very frustrating.

It doesn’t help that the save system is restrictive, demanding you pay three tokens with every save. These tokens are rewarded for finding most of the blue gems in each stage; you need to collect 80% of the gems to get even one token, while the other two are earned when you find 90% and 100%. You can earn tokens by repeating levels, so it’s possible to grab enough tokens to save after every stage or two. But it’s enough of a cost that further amplifies the sting death carries.

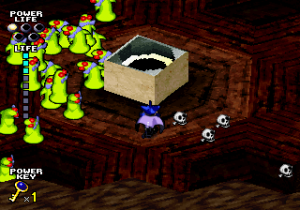

Not that Willy Wombat is completely merciless. In addition to being able to exit the level from the pause screen, there’s canisters dotted about to partially restore your health, and you can find white magic orbs that permanently grant you an extra hit point for every five collected. Hidden in special areas are coloured books that, when read out by the mysterious old man minding the save points, unlock room-clearing FORCE attacks you can grab and activate by holding A and B.

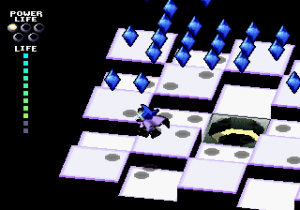

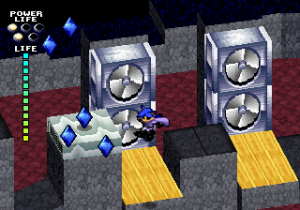

You’ll eventually get strong enough to handle most obstacles, but the early game starts out rough if you’re not playing carefully. This opening slog is further aggravated by how drab and repetitive the first world is with its endless caves and lava pits. The rest of the worlds offer much more stage-to-stage variety, ranging from city streets and temples to surreal landscapes of ice and desert. The second world is a notable highlight with its mix of broken highways, churches, town squares, and sewers.

The level designs also improve, presenting a mix of linear action stages where you go straight to the end and complex locales that ask you to solve their puzzles by activating switches and collecting keys. They’re usually clever and intuitively designed enough that it’s satisfying to solve them without ever getting truly lost, though there’s signposts and green platforms that display an overhead map to keep you oriented.

Some puzzles do drag, particularly the ones that warp you back a considerable distance if you screw up, and that can happen due to the somewhat sluggish controls not living up to the responsiveness required. This comes to a head in the final world, which is full of fittingly tough but bothersome jumping puzzles involving conveyer belts, tight platforms and even tighter timing. But its heart, Willy is a well constructed game. It’s fun to take out crowds with your boomerangs, gimmicks and ideas build on top of each other as you progress, and there’s always something new around the corner to uncover.

In addition, the story has a surprising focus, featuring cutscenes every few levels that flesh out the narrative and attempt to explore themes of free will, living in a perfect but passionless society, and the worth of eternal life. This doesn’t quite work out, with characters standing around and rambling on topics that only get a surface level treatment (often accompanied by the camera rotating endlessly as its sole cinematic flourish). What stands out most is how, perhaps due to the game’s originally planned North American release, the voice acting is entirely in English. The voices tend to fit the characters, but the performances suffer from clumsy direction that results in a lot of disconnected flat deliveries.

Visually, Willy goes for pre-rendered 2D sprites against fully 3D environments, and runs quite well despite how many characters can appear onscreen. The shiny toon artstyle for the characters gets the job done though little else, and the lifeless environments feel appropriate for the barren wastes but can sometimes become boring. The character designs were provided by Susumu Matsushita, best known in the gaming world for his Necky the Fox mascot who adorns countless Weekly Famitsu magazine covers, and is also responsible for the character designs to the Adventure Island, Motor Toon Grand Prix and Maximo games.

The sound effects efficiently convey the impact of dashing around, hitting switches and attacking enemies, while the music (composed by Masayoshi “Chamy” Ishi) goes for a funky sound full of shredding guitars, grooving drums, and smooth electric piano chords. The tracks are generally good, creating a cheeky vibe that compliments Willy’s defiant attitude, but their short length relative to the levels means they get repetitive after a while. Incidentally, this can stand alongside Symphony of the Night as a 1997 action game with an inexplicable R&B credits ballad in the form of “Fearless Heart”.

Willy Wombat would be Westone’s last platformer before pivoting to gal games, but despite its flaws, there’s plenty on display in its design and storytelling ambition that shows the studio’s ability to do something more with a well-trodden genre. It’s worth trying if you’re into action titles, and it’s quite easy to get into thanks to the voiced dialogue and most of the menu text being presented in English.