- Life is Strange

When we think of games, it’s often simplistic puzzlers, cute platformers or explosive action titles that come to mind. Which is no huge surprise, as games have traditionally been sold as entertainment or toys. Their capacity to give us fun, thrilling and joyful experiences is very well-established at this point, but throughout the years developers have quietly honed their artistry, using their work for self-expression. It isn’t true anymore to say that very few games have touched on the human condition. However, most that do merely flirt with the idea, or imbue what would otherwise be boilerplate science fiction or fantasy with a degree of endearing humanity. Very few games say anything about life in a way that creates much relatability or resonates with our non-geek sides. For years, video games have been seen as mere toys, and once developers began to explore their potential to be more, many opted to aim for entirely new experiences rather than work with more established mechanics. What emerged are titles like Gone Home or Dear Esther, often half-derisively described as “walking simulators,” for their lack of familiar game structures. These games are worth celebrating for expanding what the medium can be, and have their own strengths and drawbacks, but for a little while, the idea of employing more traditional mechanics in service of telling a story felt forgotten as artists made intricate but solitary environments, big-budget developers rushed to out-Hollywood each other, and indies wallowed in 8-bit nostalgia.

Life is Strange occupies an interesting place in the medium. Its point-and-click DNA is easy to spot and its central mechanic is similar to tricks employed by some of the most celebrated traditional games, but it turns all of these toward telling a story that’s more about longing, regret and ordinary life than fighting an Evil Empire, saving a fantasy world or embarking on a quest for revenge.

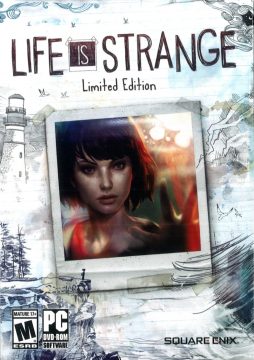

Developed by French studio Dontnod Entertainment, whose previous title had been the future noir cyberpunk oddity Remember Me, and published by Square Enix, Life is Strange was released in 2015 in five serialized episodes. Each installment takes about three hours to complete and follows a TV episode format with plenty of melancholy montages, dramatic climaxes and agonizing teaser endings. Early episodes were marred by poor lip-syncing, uneven writing and a number of game-breaking bugs, but most of these issues got addressed in future releases or fixed in patches. Critical response to the game has been largely positive, although incredibly divisive – something probably owed more to the game’s touching on so many taboo or mundane topics than anything reflective of its quality.

Life is Strange is more a story that happens to be a game, than a game that happens to tell a story. That’s not to say the game itself is lacking in interactivity, but it’s always apparent that narrative drives the mechanics. In some ways, it’s a bit chimerical; it wears its narrative influences proudly on its sleeve, but so too does it wear its roots in traditional gameplay. Other recent story-driven games have been criticized for telling stories in past-tense through characters that function as passive observers, as well as choices that don’t seem to matter in the end. Life is Strange shares a bit more in common with European adventure games than these other titles, and takes an approach that skirts either issue. By giving players a well-defined protagonist and detailed environments to explore peopled with a variety of characters, the game establishes a greater sense of presence, sidestepping the issue of a story received through journal entries and memoirs. While some of its choices may look arbitrary, it’s careful to make sure every action sparks a reaction, so decisions will generally feel meaningful even if players can’t dramatically alter a scenario.

The story follows Max Caulfield, an ordinary if somewhat taciturn teenager attending Blackwell Academy, a special arts and sciences academy for high school seniors in the U.S. Pacific Northwest town of Arcadia Bay. As a budding photographer, Max is always on the lookout for the next great shot. Which is how she ends up lingering long enough to witness the murder of another girl in the school’s toilets – and in her shock and denial, incidentally discovers she has the power to rewind time. The temptation to fix mistakes, however great or small, is immediate and immediately acted upon, as Max rushes back to the bathroom to change history. Haunted by visions of an apocalyptic Storm and increasingly aware of bizarre ecological phenomena, Max teams up with her freshly un-murdered friend to unravel the mysteries of Blackwell and her own powers. What unfolds from this premise is something closer to Twin Peaks, Donnie Darko or a Gregg Araki film than a stereotypical videogame plot, balancing a sense of apocalyptic urgency with a wistful feeling of everyday life. As much teen drama as science fiction, Life is Strange aims for a sense of reality most games are afraid to touch, dealing with surprisingly real topics like depression, disability, sexual assault, suicide, financial hardship, rocky relationships and pining for childhood simplicity, with enough slices of life to make a whole pie. Even when it falters, it has to be admired for sheer ambition and uniqueness.

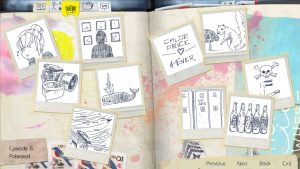

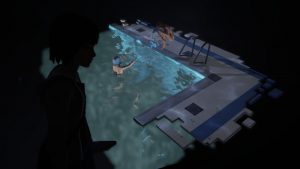

Aesthetically, the game opts for stylized photorealism, with impressionistic blurring of details and distances. Anything where painful levels of detail might be expected in an HD game instead look literally painted-on. Visually, it’s a nice compromise between realism and fantasy. As progress is made, Max will fill out a wholly gorgeous scrapbook-style journal filled with doodles, notes and photos that ends up being far more elaborate than it needed to be as a functional quest log. Little details like this are unnecessary to the core game, but add up to make a more believable world. Aurally, the game features music by many well-known artists like Sparklehorse, Mogwai and Amanda Palmer, as well as an original score by Jonathan Morali. Most of the soundtrack falls within a soft, melancholic “indie” sound that suits the game incredibly well.

Gameplay is simple, intuitive and substantial enough to provide things to do without ever allowing the focus to drift from story. The influence of point-and-click adventure titles is immediately obvious. Objects that can be interacted with are highlighted and labeled in a style resembling diagrams for school notes. Conversations follow a typical four-way dialogue tree. The interface is designed with controllers in mind, allowing for better streamlining and far less pixel-hunting. A few moments require locating specific items which are usually logically placed, but sometimes…not so much. These lapses into adventure game logic are few, and the game mostly uses the item hunts as an excuse to have the player explore the environment, but a couple do end up feeling like filler.

A small number of more traditional puzzles appear here and there, most of which are startlingly logical and can be solved fairly enough with a little thought. Conversing, leisurely exploring environments and rifling through various bits and bobs – letters, bills, journals, household objects, etc. – in a Shenmue-like fashion, makes up the bulk of interaction, and often provides small glimpses into the wider world or heads of others. Though never in a hurry to move the player along to the next event, a fairly wide variety of gameplay gets employed (there’s even an awkward stealth sequence, near the end). Luckily, most of whatever you’re doing is directly relevant to the narrative – conversations can be redone with insights gleaned during a prior “instance,” incidental items will sometimes have obvious significance to the story and going through other people’s stuff grants greater understanding of their lives in an around-the-edges manner unique to games. This last aspect often helps fill in some gaps in characterization, and contributes to how well-realized the game’s cast is.

Characters

Max Caulfield

The time-traveling teenage protagonist, Max is something of a geek everygirl, nerdy and shy without being actively antisocial. A well-drawn character without too many problems of her own, she still has enough personality not to be simply a player cipher. Prone to outbursts of, “Wowser!”

Chloe Price

Max’s childhood best friend, Chloe is an outgoing and adventurous foil to the more reserved Max. Initially introduced by witnessing and then preventing her murder, she comes to be the most central character alongside Max. While happy to be reunited with best friend, Chloe does have a lot of believable resentment toward Max for not keeping in touch, and gets some fairly extensive character development throughout the game.

Nathan Prescott

Chloe’s would-be murderer, Nathan is the son of powerful and wealthy real estate mogul Sean Prescott. Used to getting his way, emotionally unstable, implicit in all sorts of sketchy goings on, Nathan acts as an antagonist for most of the game. He is eventually humanized somewhat, though still kind of a monster.

Kate Marsh

Max’s quiet, keeps-to-herself Christian classmate, Kate has been bullied and harassed by other students for some time before the game begins. As she opens up, it becomes apparent she’s dealing with several difficult situations.

Warren Graham

Chemistry student and something of a nerd mentor to Max, Warren often acts as your adviser and co-sidekick. Edged out of Max’s life by her reunion with Chloe just a bit, Warren is the ever-faithful painfully obvious hopeless romantic who’s always got Max’s back. Though he could have ended up a creepy “Nice Guy?”, Warren mostly serves to be genuinely helpful regardless of how a situation affects him.

Rachel Amber

Life is Strange’s own Laura Palmer is all things to all people. Nearly everyone in town knew her, and nearly everyone saw a completely different side of her. Adored by any who remember her, Rachel vanished sometime before Max returned to Arcadia Bay, and uncovering the details of her disappearance takes up the largest portion of the Mystery Solving component of the game. She is the major focus of the “Before the Storm” side-story released after the original Life is Strange.

Since Max is a photography student, it’s natural enough for the dialogue and themes to occasionally touch on the subject, but there are also a number of optional photos that the player can take. Most of these are the kind of odd but everyday incidental subjects that a budding photographer would probably want to capture. Very few are immediately obvious, but the game offers clues in the form of doodles in Max’s journal that update at the beginning of each episode. Some can be a little opaque, but there is a gently rising curve to their obscurity. There isn’t any real reward for completing all the photos, but it does add some extra elective challenge. Additionally, each photo earns an achievement named after an aspect of photography, which is kind of neat.

Max’s power to rewind time makes the central mechanic, kicking off and remaining central to the main story. Pulling off a rewind is a fairly simple affair: pressing the right mouse button (or left trigger, on consoles) will reverse time, which can be accelerated with another button. A spiral icon indicates the amount of time available to rewind?go too far, and Max gets a headache and has to stop. Key moments are marked with open circles along the spiral. Progressing often involves first allowing a situation to play out naturally while the player collects clues, then rushing back to a previous point and redoing everything with greater knowledge. This is used both for gleaning information from uncooperative characters, as well as simple but satisfyingly paradoxical light puzzles.

There’s a subtle narrative significance to the chronological caprice, too: it allows the player to redo any situation with greater expertise on each cycle. Knowing there’s a safety net encourages trying different things, then rewinding ready to take on a challenge with greater preparation. It can be interesting to redo certain scenarios just to see the alternate outcomes. It’s easy to get used to this carefree way of exploring different actions without concern for permanent consequences, so it comes as a shock when the game begins dropping the safety net and reveals what it’s been doing all along. Because the game relies on autosaving checkpoints, short-term decisions can be remade to perfection, but the ultimate consequences remain obscure to the player as minor actions stack up and eventually snowball.

While there technically are failure states, there isn’t any Game Over, so there’s always a way forward, and even after it starts coming back to bite you, Max’s power imbues your progress with increasingly determined hope. Who wouldn’t be tempted to undo an embarrassing or painful moment and replace it with something better? Who wouldn’t jump at the chance to erase some personal trauma or resurrect lost loved ones? Of course, no moment is ever actually perfect, and most choices in real life are merely decisions, neither “right” nor “wrong,” with unique pros and cons. Rewriting history one way always ends up altering it in other ways and the world never stands still for anyone.

What’s fascinating about Max’s power is that it becomes so easy to fix any immediate mistake that long-term effects utterly blindside her, and her very experience of the world becomes increasingly short-sighted. Although it’s a fantastic element, the time travel aspect thus ends up being about something much more human: fixing mistakes and making so many new ones in the process, being unable to let go of some unattainable ideal vision of the world, realizing how little control we ever have over our lives even if we could Groundhog Day our ways to perfection. It’s an interesting inversion of the typical videogame power fantasy, being given a chance to rewrite your own history and coming to see it as something of a curse that always draws you back to the traumatic, powerful moments you’d be better off moving on from. In revisiting the past so often to alter the present, it’s easy to lose the moments in which life is simply good. The game offers a numbers of these in several forms: furniture that can be used to sit and just be for a moment; a guitar in Max’s room that can be played at leisure; many episodes open with Max lying in bed, unmoving until the player prompts her. Aside from some internal soliloquies, nothing happens in these moments, yet they’re where the game consistently shines.

For all its time-bending parallel tripping and crescendos of murder mystery drama, Life is Strange is ultimately about the awkward but powerful reconnecting of friends (who may be a little more) and the daily struggles of the people around them. Here, a family struggling with the financial burden of a disabled child. There, a bright young artist suffocating from the expectations of adults. Everywhere, people who care but aren’t quite sure how to show it, quietly living private dramas that range from the specter of PTSD to awkward nerd crushes. Some of this becomes a bit much – the game takes on a lot of taboo topics – but much of it is handled with uncharacteristic maturity. What could have been a callous gamification of a serious subject early on becomes a shift toward underlining an underlying theme of being unable to make other people’s choices for them, and the need to be there for one another despite the risk of pain and the guilt of potentially “failing” others.

Games often take more diverse influences than we readily acknowledge, Satoshi Tajiri’s bug collection and Shigeru Miyamoto’s childhood adventures aside. Even so, the medium overflows with works that draw from a very small number of the same repeating sources; Ghibli, Dungeons and Dragons, Star Wars, J.R.R. Tolkien. Nerd stuff. At some point, those influences begin to feed on each other, and we end up with games influenced by other gamesinfluenced by geek staples. Life is Strange, by contrast, fits in a little better among literary or cinematic works than other games. The serenely suburban but secretly sinister worlds of David Lynch are an apparent and nodded-to influence, as are a considerable number of other works. Ray Bradbury, The Twilight Zone, the Final Fantasy movie, Ansel Adams and other highly-regarded photographers; Life is Strange enjoys namedropping, but often takes inspiration from rather than mimics other works, a distinction one only need look at Deadly Premonition to understand. Even comparing it to the thematically similar Gone Home feels a bit more forced than something like Audrey Niffenegger’s The Time Traveler’s Wife or Chris Ware’s Building Stories. Masaaki Yuasa’s anime series The Tatami Galaxy, in which a college freshman continually rewinds time in search of a perfect year, feels like a much closer cousin than the somehow mechanically similar Heavy Rain. While opinions vary on how well the game handles them, it is completely unafraid to reach for meaningfully adult ideas in a way that even other narrative-pushing titles shy away from, and isn’t ashamed of it.

Though the narrative is one of the more dramatically intense in games to date, it’s the sense of reality underneath that often makes that drama really work. As a native Arcadian returning from Seattle, Max’s perspective drenches the game in homesickness. Rather than a game about being a teenager, this becomes a game about remembering being a teenager. Games like Shenmue and Persona 4 offer superficially similar experiences with intricately detailed mundane environments and ordinary high school life, but what Life is Strange does with its parts ends up making a completely different kind of whole. It’s moments like sitting alone in a worn-out seat atop a trashed boat in a junkyard and admiring the pleasant afternoon, or wandering through a very well-realized working class American house while listening to Angus & Julia Stone’s “Santa Monica Dream” that give the game a special atmosphere. A mid-game sequence has the player caring for and spending time with a disabled friend, during which nothing particularly exciting happens, but the conversations with other characters reflect a degree of reality and depth one normally wouldn’t find in a game. This combination of detailed, believable locales, realistically multifaceted characters and wistful music work toward feelings of nostalgia and melancholy. Where Persona seems preoccupied with capturing the adolescent experience, Life is Strange takes more interest in filtering the difficult aspects of teenage life through a bittersweet longing of adulthood looking back.

We’re always looking back, and that’s why the fantasy of the game is so compelling. What the primary story builds toward is a kind of slow-boil Trolley problem centered around the questions of, “What would you do for a second chance?” and, “What sacrifice is love worth?” This has had the effect of making the game (and especially the ending, and other major branching points) considerably more divisive, but not especially in a negative way. The kinds of questions asked by the game will have as many answers as there are people to answer them, so it’s if anything an indication of the game’s success that critics and fans alike seem unable to agree on any of the details. A huge part of the controversy over the ending is the lack of a perfectly happy conclusion. In a medium where wish fulfillment is the norm, it’s unusual to have a game in which you simply can’t save everyone or do everything perfectly. Sacrifices have to be made, and while the choice can feel binary or arbitrary, either decision can be justified and the outcomes are equally well done.

Perfection is impossible to realize both in life and games, and so Life is Strange is not without its warts. The puzzles and gameplay aren’t particularly challenging or complex, but neither are they especially intended to be. More relevant are criticisms of the storytelling. Many have found the writing at times cringe-inducing, and criticized the excess of unrealistic teen jargon. It is worth noting that these criticisms were taken into account, and the quality of writing does improve over the course of the game’s episodes. Late in the game, a rather cartoonishly over the top villain is introduced, which feels rather unnecessary. Up to that point, the story had got along well without any definite villain, and their motivations, once introduced, prove disappointingly shallow. Players are also divided on some of the more emotional scenes and real-world themes, with some feeling them quite well done and others that the game fumbles them somewhat. Some of the voice acting done for minor characters isn’t stellar (another echo of Shenmue), and a few areas highlight that the game’s realist-impressionist aesthetic is in part meant to cover up lower graphical fidelity. Still, it’s difficult to pin down many legitimate complaints or flaws that any group of people can agree on; the diversity of thought on the game’s strengths and weaknesses is more often a symptom of healthy discussion than it is a condemnation of the game’s faults. Conversations on the game often step over its faults (in writing, voice acting, graphics or puzzles) to debate issues raised by its narrative, showing it succeeded at least in telling a story audiences found engaging.

Ultimately, Life is Strange is a unique experience that manages to add a great deal more depth to the maturing medium. Its mechanics may not be entirely original, and its themes and ideas may have been utilized before in other media, but it integrates them naturally, and shows its influences without being quite so defined by them as other games, adding up to a singular whole. Perhaps the strongest praise one could give is to say it does a very nice job being what it is, something that most ambitious games to date have struggled with for one reason or another. If it stumbles here and there, it more often stands up straight and opens doors others have been afraid to for years, reassuring us that the house videogames built is a lot larger and more exciting than we’d been led to believe.

Links:

Official site: including a list of resources for those affected by some of the content

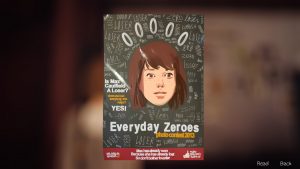

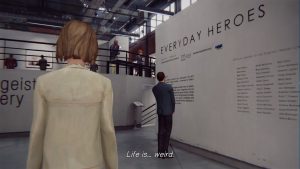

Everyday Heroes: A photography contest held by Square Enix mirroring the in-game contest of the same name.

Blackwell Podcast: Unofficial podcast series featuring interviews with many of the game’s creative staff including lead writer Christian Divine and actors Ashly Burch (Chloe) and Hannah Telle (Max).

Life is Songs (Time): An original album by independent musician Koethe inspired by the game that’s drawn some attention.