In spite of a wide range of NES peripherals made available by Nintendo in the US and Europe, markets outside Japan were deprived of the company’s most ingenious addition to the original 1983 hardware: the Famicom Disk System, released in 1986 exclusively for that country. Exploring the full potential of the system’s hardware, this 2.8″ x 3″ floppy disk operated unit allowed players to benefit from a number of advantages, one of them being the ability to create larger game programs equipped with a much needed save function that was not feasible in the early Famicom ROM Cartridges. Branded titles such as the The Legend of Zelda would not have been released at the time if not for the Disk System, as the battery saving function would only appear later that decade. The technology behind the production of cartridges was dramatically improved around the end of the 1980s, namely with the introduction of custom chips in selected releases. The cartridge technology was widely adopted at the time and, perhaps invariably, the Famicom Disk System was unable to stand the test, its production having been halted a few years later.

Motivated by the impressive technology of the Disk System, young multimedia artist and visionary Toshio Iwai, later responsible for SimTunes and Electroplankton, was the first to envision a dynamic and reactive use of music as the central element of a genuine videogame. His project, designed along with SEDIC and published by ASCII Corporation, was given a strange albeit contagious presentation for that which is easily one of the most singular and innovative games of all time. Named after its congenial robot protagonist, this stroke of genius came to be known as Otocky.

At present, music video games have become a key genre within the industry, spanning from abstract experiences such as the honorable work from designers Masaya Matsuura and Tetsuya Mizuguchi; free form music programs such as the famous Mario Paint music mode, the uncanny PSOne sound mixer Fluid or even the recent Wii Music; to the leisurely party games like Singstar, Guitar Freaks and its various offshoots. Long before any of these titles sold on account of the appetizing mixture of rhythm and video game entertainment, Otocky inaugurated the genre, not as a primitive experience, but as a mystifying blend of visual and aural elements that was unprecedented. The cover also features Natsuki Ozawa, a popular singer at the time, though she was just used to promote the game, and her music doesn’t have much to do with it otherwise.

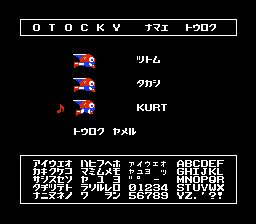

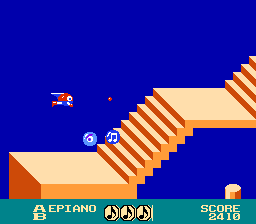

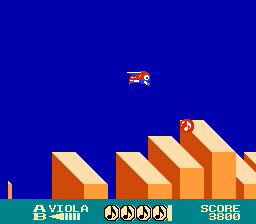

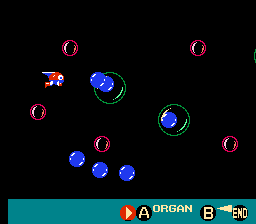

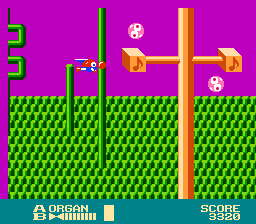

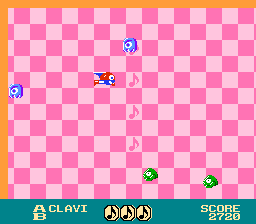

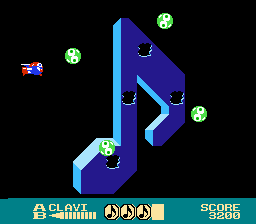

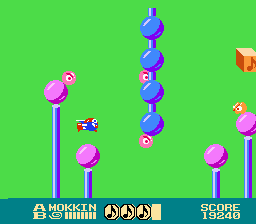

At its core, Otocky respects a classic shoot-em-up scheme composed of side scrolling levels and boss stages. The main objective lies in the recollection of musical notes, scattered around the stages either freely or cleverly concealed in item boxes. Gathering enough of these notes will enable the player to visit the level bosses, consisting of gigantic music notation symbols. Otherwise, until this gauge is replenished, the level will continue to repeat itself perpetually. However, unlike a common shooter, the mechanized avatar will only shoot projectiles as part of a distress attack, assigned to the B button. The main action of the character consists of throwing spheres by pressing the A button together with one of the eight D-Pad directions. These random red and blue spheres, used for picking up items and defeating enemies, can only travel a short distance and will always return to their sender.

The process of learning enemy motion patterns and item locations is essential in mastering Otocky. Because each recollected item is replaced in the next reiteration of the level by an enemy, including the items concealed in boxes, the game requires the player to remember the positions of untouched boxes or elusive items not caught in the previous run, while battling against an increasing group of opponents.

What is most compelling about this title, well over twenty years of age, is the advance it introduced in that particular period of history. Apart from the astounding Boss theme, Otocky does not have a soundtrack of its own, but rather a predetermined beat or bass loop that plays as aural background. According to the different direction in which the player tosses the spheres, a different musical note will be emitted: it is in the repeating of this action that single musical notes become a chained melody, each of them set to match the background’s rhythm in a preordained scale so that the interactive and real-time phrase will never feel inaccurate. Consequentially, the game presents a scenario where the music is not entirely pre-conceived as it is, in fact, created by the player in result of the actions he performs during the game.

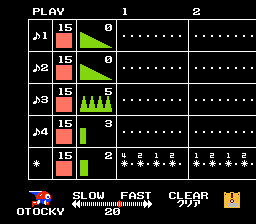

Several instrument voices are also available throughout each stage and they range from strings, keys, brass, percussion, synthesizers, just to mention a few, each bearing a distinct sound in spite of the Famicom’s limited processing capabilities – quite an exploit, considering the fact that the system possessed no more than 5 simultaneous sound channels. The game system was indeed so functional that the designers included a “BGM Mode” where enemies and items were suppressed: when unlocked, it allowed the player to engage in the free creation of music by simply travelling across the emptied locations.

Several instrument voices are also available throughout each stage and they range from strings, keys, brass, percussion, synthesizers, just to mention a few, each bearing a distinct sound in spite of the Famicom’s limited processing capabilities – quite an exploit, considering the fact that the system possessed no more than 5 simultaneous sound channels. The game system was indeed so functional that the designers included a “BGM Mode” where enemies and items were suppressed: when unlocked, it allowed the player to engage in the free creation of music by simply travelling across the emptied locations.

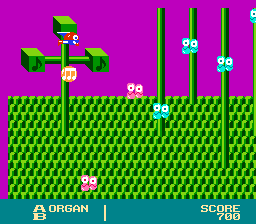

The design of levels is essential to the comprehension of the game experience. Each level is a singular abstract composition defined by elementary shapes that allude to the aesthetics of Modern and Optical Art, with a keen taste for geometry and powerful color contrasts. The selection of the palette appears invariably as a result of the music genre featured in each phase, revealing a careful design of the game beyond the engineering of sounds. Each new stage, like a new step in a perfectly formed ladder, will require an increasing amount of memorization from the player, as well as prodigious skill.

With this exceptional debut, Toshio Iwai demonstrated not only his devotion in creating new forms of musical expression, uniting experimental art and computer-generated software; but also a set of impressive aptitudes in developing an experience that exceeded the prevailing conception of what a videogame could be. Beyond the delightful and challenging gameplay elements, his work embraces a deeper layer of contents, together with a general impression of awe and astonishment that can be felt as the player immerses in this real-time improvisation. There are hardly any adjectives that can fully describe this highly imaginative, rare and fully interactive synaesthesia of musical notes, measures, beats and visual patterns. Not only was Otocky unprecedented in the achievement of such defiant results, it perfected them with an unusual consistency. Two decades after, Iwai’s masterpiece still begs to be played as a document of inestimable value, a prescient treaty on the evolution of home videogames that should not to be considered second to any celebrated Famicom title.

Links:

Vimeo Otocky gameplay video from dieubussy